|

|

|

alternatively

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Download: Classicsonline

|

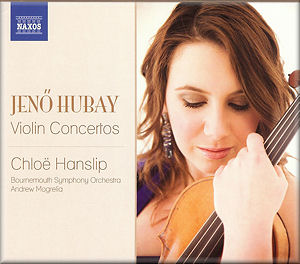

Jeno

HUBAY (1858-1937)

Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 21, “Concerto Dramatique”

(1884) [30:30]

Violin Concerto No. 2 in E major, Op. 90 (c. 1900) [26:45]

Scènes de la Csárda No. 3, Op. 18 (c. 1883) [7:13]

Scènes de la Csárda No. 4, Op. 32 (c. 1886) [6:19]

Chloë Hanslip (violin)

Chloë Hanslip (violin)

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Mogrelia

rec. Lighthouse, Poole, U.K., June 2008

NAXOS 8.572078 [70:46]

NAXOS 8.572078 [70:46]

|

|

|

From the opening notes of Op. 21 the listener is left in no

doubt that Jeno Hubay was a fully paid-up member of the late-Romantic

school of composer-performers. The name of Liszt, a fellow Hungarian,

comes to mind, but it is Henri Vieuxtemps who is the most frequently

evoked in connection with Hubay. Comparing the music on this

disc, however, with what little I have heard of the Belgian

composer, it is Hubay’s that seems the more interesting. It

is easy to listen to and not particularly challenging, but it

is certainly not pale or unmemorable. It is well crafted but

any reader who thinks I am damning with faint praise here should

lose no time in acquiring this disc, as I am convinced it will

bring much pleasure. There are stock gestures, to be sure, and

many moments where the composer’s command of formal matters

is rather self-conscious. One can almost hear him saying “it’s

time for a short cadenza now”, whereas a master composer will

contrive to allow such events to occur seamlessly in the overall

structure. The first movement of the First Concerto is quite

dramatic for much of its length, but boasts a very affecting

second subject. The slow movement is perhaps the pearl of the

work. Bruce Schueneman, in the booklet notes, describes it as

“gorgeous”, and that is a perfectly appropriate word. The solo

instrument really sings, indeed, hardly stops for breath throughout

the movement. The finale opens in more conventional manner with

a few rather commonplace virtuoso gestures, but after a while

the music slows and calms – in the self-conscious manner outlined

above, one might think – for a quieter section. When it comes,

though, this really is lovely, and throughout the work one is

surprised by the freshness of the melodic writing, if not its

total originality.

The Second Concerto is perhaps less consistently inspired, but

is a most satisfying listen nonetheless. It would take a thesis

to explore why neither of these works measures up to the greatest

in the repertoire, but with such consistently pleasing music

there is no real need to ask the question. One should just to

submit to it and enjoy it.

The disc is completed by two short pieces for violin and orchestra

entitled Scènes de la Csárda. The czárdás

is a Hungarian dance form, usually beginning with a slow introduction

and ending with a faster, often rather wild section. An excellent

example is the fake csárdás sung by Rosalinda in Strauss’s

Die Fledermaus as a way of convincing the assembly that

she really is a Hungarian Countess, but I don’t think anyone

hearing these works would have any doubt that Hubay really was

a Hungarian composer. The writing for the solo instrument is

virtuoso in nature, and that for the orchestra is brilliantly

colourful and evocative. Both works would make marvellous encores

for a visiting soloist, and as such, would bring the house down.

If the composer were alive today he would be clasping his hands

in gratitude for the advocacy of Chloë Hanslip. She rises to

the fearsome technical demands of these works without flinching,

with strong, rich tone and absolutely spot-on tuning. More importantly

still, she seems totally convinced by, and committed to this

music, bringing to it an ardent romanticism that serves it perfectly.

I can hardly wait to know what she is going to record next.

She is admirably supported by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

in music which, though colourfully orchestrated, is conceived

mainly as a vehicle for the soloist. Andrew Mogrelia directs

the ensemble with sensitivity and meticulous attention to detail.

Bruce R. Schueneman contributes a booklet note that tells you

all you need to know to enjoy this disc. The recording is excellent.

All this is available at the usual Naxos price. What are you

waiting for?

William Hedley

see also review

by Jonathan Woolf

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews