|

|

|

alternatively

CD: Crotchet

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

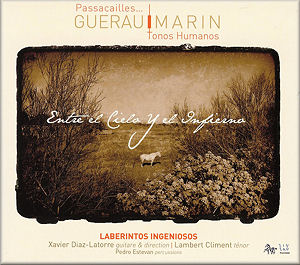

Francisco GUERAU

(1649-1722)

Marionas (1694) [5:45]

Passacalles por el primer tono (1694) [9:20]

Gallardas (1694) [5:30]

José MARÍN

(1618-1699)

La verdad de Perogrullo [1:51]

Ojos, pues me desdeñáis [3:59]

Tortolilla, si no es por amor [2:37]

Mi señora Mariantaños [1:40]

De amores ye de ausencias [2:37]

Si quieres vivir [2:59]

Que ben canta un ruiseñor [4:28]

Si quires dar, Marica, en lo cierto [2:49]

Aquella sierra Nevada [5:35]

Al son de los arroyuelos [2:47]

Montes del Tajo [2:46]

Sepan todos que muero de un desdén [3:53]

Laberintos Ingeniosos: Lambert Climent (tenor), Pedro Estevan (percussion),

Xavier Díaz-Latorre (guitar/direction)

Laberintos Ingeniosos: Lambert Climent (tenor), Pedro Estevan (percussion),

Xavier Díaz-Latorre (guitar/direction)

11-15 June 2007, L’église évangélique Allemande, Paris

Texts and translations included

ZIG-ZAG TERRITOIRES ZZT090301 [58:40]

ZIG-ZAG TERRITOIRES ZZT090301 [58:40]

|

|

|

Any account of the life of José Marín is likely to make him

sound like a picaro, one of those rascally and scandalous

‘heroes’ of Spanish picaresque fiction, a man living on his

wits, not too troubled by moral boundaries and living a life

full of reversals of fortune. Born in Madrid, he sang in Philip

IV’s chapel choir – and he committed more than one murder; he

travelled to Rome (where he seems to have been ordained) and

apparently to the Indies; he was exiled from Spain for theft

and he may have spent some time in the galleys. He was unfrocked

and, then, after due repentance his clerical licence was restored

and he ended his life back in Madrid working as a musician,

often for the theatre. He might have stepped out of the pages

of the Relaciones de la vida del escudero Marcos de Obregon

(1618) by Vicente Martinez Espinel, himself a priest who, at

the very least, kept criminal company; or one might meet him

in one of the contemporary Spanish author Artur Perez Reverte’s

entertaining Captain Alatriste novels.

When we turn to listen to Marín’s songs we can surely hear in

them the wealth of human experience, pleasant and unpleasant,

moral and immoral, that their composer brought to their writing.

His subjects may seem the merest clichés of the day – the usual

unrequited love, full of disdainful eyes and tearful sighs;

here the nightingales sing out loud, as they so often do, and

the turtle-doves moan with regularity. But what can so often

seem the merest routine of well-nigh meaningless convention

is here invested with real feeling, with a striking passion

and often with a rueful note of experience. It helps that the

texts he sets are often of higher than average poetic quality

– one is by no less than Lope de Vega. Yet it is Marín’s commitment

to emotional truth, his ability to draw, not just on a familiarity

with the musico-poetical conventions of his age, but also on

a wealth of personal experience that gives his songs their particular

power.

The most significant surviving collection of Marín’s songs is

to be found in a manuscript (MV 4-1958, Mv.Ms.727) preserved

in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. The songs contained

in that manuscript show what an original and relatively unconventional

musical mind Marín had, full as they are of unexpected harmonic

twists and turns and of very expressive vocal lines, often vivid

in their word-painting. Some will doubtless have made the acquaintance

of some of these songs in the recording made by Montserrat Figueras,

Rolf Lislevand et al. on Alia Vox (AV 9802/A review).

To say that this new recording by Laberintos Ingeniosos fully

stands up to comparison with that fine earlier collection is

to say that it is highly recommendable; the two CDs are fascinatingly

and rewardingly different in their interpretations and both

are very well performed; if you like either you will surely

want both.

Here the tonos humanos of Marín are coupled with a small

selection from the virtuosic guitar music of Francisco Guerau,

as printed in his 1694 volume Poema harmónico compuesto de

varias cifras por el temple de la Guitarra española (‘Harmonic

Poem made up of Various Tablatures for the Temple of the Spanish

Guitar’). The volume contains 27 pieces, all of them essentially

sets of variations, and also, since the work is partly didactic

in nature, a short treatise on tablature, notation and ornamentation.

Guerau appears to have led an altogether more ‘regular’ life

than Marín did. He was a choirboy in the royal chapel in Madrid

and then an adult chorister there; he, too, was ordained as

a priest and in 1700 became a chaplain in the royal chapel.

The guitar pieces from the Poema harmónico are technically

demanding and, while retaining a certain apt earthiness also

have a prominent gravity that goes beyond purely ‘popular’ idioms.

There is music of real beauty here – notably in the ‘Passacalles

por el primer tono’ – and Guerau’s use of ornamentation and

rapid scales makes for consistently interesting listening. Xavier

Díaz-Latorre is a stylish interpreter of the music, obviously

fully at home with Guerau’s musical language and making attractively

varied use of timbre, capable of both dash and subtlety, rapid

flourishes and moments of meditative melancholy. Incidentally,

anyone taken with these three pieces by Guerau should track

down a copy of Gordon Ferries’ equally fine performances on

Marionas: The Guitar Music of Francisco Guerau (Delphian

DCD 34046).

There is much to admire and, above all, to enjoy in this finely

chosen programme.

Glyn Pursglove

|

|