|

|

|

alternatively

CD: AmazonUK

AmazonUS

|

Frédéric CHOPIN (1810-1849)

24 Preludes, op.28 [45:03]; 2 Ballades: No 1, op.23 in G minor [10:49];

No. 4, op. 52 in F Minor [11:50]

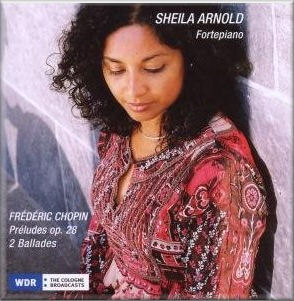

Sheila Arnold (fortepiano)

Sheila Arnold (fortepiano)

rec. August 2009, location not specified.

AVI MUSIC 8553183 [67:42]

AVI MUSIC 8553183 [67:42]

|

|

|

Historically informed performance practice, along with associated employment of period instruments has become a major force in live performance and recorded classical music. There are famous musicians who express antipathy for such undertakings and many others who embrace it with ebullience. If one discounts the superior/inferior debate, there is another aspect that has much general appeal: the opportunity to hear renditions of music by the great composers in much the same way that they would have heard it.

The market for recordings of the review disc’s programme is currently well supplied. They generally have one thing in common: utilization of modern pianos. The review disc employs an Erard piano manufactured in 1839 which is close to the time when the op.28 Preludes were composed. For those familiar with the programme played on a modern piano, listening to it played on an Erard will be an enlightening and unique experience. One expert noted: ‘Today’s piano produces lone, sustaining liquid notes. In comparison to a fortepiano the notes die away much more quickly and this gives a completely different texture to the music.’

For many years Sheila Arnold has been developing a parallel specialty in historical keyboard instruments, particularly fortepianos from 1790 to the present. She is particularly interested in the technique required to master historical keyboard instruments while applying the results of performance practice research. Close study of the instruments and the original scores reveals that each instrument, in terms of phrasing, requires a unique approach. The works thus gain a new, utterly different dimension of sonority.

While Chopin had access to an Erard, it was his Pleyel piano about which he made the following comment: ‘Pleyel pianos are the last word in perfection.’ Constructed by his close friend Camille Pleyel, the pianos of his choice were a gift from the maker, given with the caveat that Chopin would recommend the brand and receive commissions on their sale. After fleeing to London in 1846 from revolution-stricken Paris, Chopin lived in Mayfair where he had access to instruments by both John Broadwood and Erard, but still appears to have preferred his Pleyel that had been brought with him from Paris. Before leaving London he sold the Pleyel for eighty pounds. Almost 150 years later it was discovered in a country house in Surrey. Instrument No. 13819 was later confirmed from Pleyel’s ledger as that belonging to Chopin.

Sheila Arnold was born in Tiruchiralpalli, Southern India and grew up in Germany. Her principal teachers were Heidi Köhler and Karl-Heinz Kämmerling. Inspiring encounters with pianists such as Imogen Cooper, Elisabeth Leonskaja, Ference Rados, Claude Frank and Lev Naumov were a fertile source of ideas. Her success in major international competitions is impressive, including the Salzburg Mozart Competition and the Concours Clara Haskil. Ms. Arnold has played in many of the great concert halls of Europe and is frequently invited to perform in international festivals. Currently she teaches at the Musikhochschule, Cologne as a professor and gives master courses.

Additionally, Sheila Arnold performs and records duets with her husband, concert guitarist Alexander-Sergei Ramirez employing period instruments. Regrettably Chopin never wrote any music for guitar but interestingly he shares a number of commonalities with a man often referred to as the ‘Chopin of the guitar.’ Franciso Tarrega was born in 1850, the year after Chopin died, and during his life-time made a number of arrangements of the pianist’s music for guitar. Both musicians shunned public appearance, preferring to play in more intimate environments with close friends. Biographer, Arthur Hedley noted that Chopin was unique in acquiring a reputation of the highest order on the basis of the minimum public appearances - fewer than thirty in his lifetime. Tarrega, also an accomplished pianist, and Chopin both excelled in the composition of exquisite miniatures; it is from this genre that the review disc programme is principally taken - the 24 Preludes, op. 28.

Commenting on the programme Sheila Arnold said: ‘Of all the Chopin works, I find that the two Ballades featured -op. 23 & 52- and the twenty four Preludes are some of the most impressive pieces for solo piano. The order chosen here reflects the way I experience these works. The Ballade in G minor literally tells a story- with eloquence, rhetoric and associations of ideas. But it ends in chaos and catastrophe. The dream is followed by a wave of supposed happiness at the beginning of the Preludes; however it immediately dries up with the death knell in Prelude No.2. The ensuing cycle confronts us with the lofty heights and abysmal depths of human existence. The last Prelude in D minor, ends with a final plunge and three shattering blows. Once more we are faced with death and destruction. Then we hear the Ballade op. 52- a reminiscence as if from afar, offering some sort of comfort. It almost sounds as if it is ‘not of this world.’

While we have here an instrument contemporary with Chopin, on the questions of performance, composition and aesthetics, his own writings are virtually silent. Only by piecing together the statements of his students, fellow composers and critics can one gain insight into these issues. Even among his contemporaries there was discussion on the ‘true’ way of Chopin(’s) playing. Mendelssohn criticized his ‘losing sight of time, sobriety, and of true music, playing in the Parisian spasmodic and impassioned style.’

To those familiar with the music, the tempi for Preludes 2, 9 and 20 may sound atypically slow. Interpreting these pieces Sheila Arnold has noted: ‘These occur to me as funeral music; the second is known to represent knells heard in some Polish villages and the 12th is definitely a funeral march; whereas the 9th seems to be something archaic and in a way grave and stern.

From the outset it is conspicuous that on this disc, Sheila Arnold has little empathy for the expressed opinions of writers who noted that Chopin could not sound aggressive, particularly on the instruments of his day. The Universal- Lexikon der Tonkunst music reference text, 1847 edition, also suggests that he lacked sound and force; that it was only in the salon that he excelled. It further reaches the seemingly incongruous conclusion that, despite these attributes lacking, he can be acknowledged as effecting a major turnabout in the art of piano playing. As required by the music, Sheila Arnold’s interpretations are appropriately aggressive and forceful; the beautiful sound she makes is one that shows the music in a new and revealing light.

This disc is well recorded and the dynamic range impressive, considering the instrument being recorded. It is difficult to assign this latter attribute to the player, instrument, recording technique or all three. Not only has the sequence of the programme reflected the way Sheila Arnold experiences the works, but her interpretations of the individual pieces mirror the emotional vicissitudes her narrative expresses.

The quest for a better understanding of the works of Chopin is unending, irrespective of the past’s magnificent contributions. In this recording Sheila Arnold makes a significant contribution to the progress of that cause.

Zane Turner

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews