|

|

|

alternatively

CD: MDT

AmazonUK

AmazonUS

Sound

Samples & Downloads

|

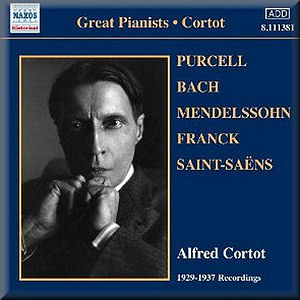

Great Pianists:

Alfred Cortot

Henry PURCELL (1659-1695)

(arr. Henderson)

Minuet in G major [2:21]

Sicilienne in G minor [1:01]

Gavotte in G major [1:09]

Air in G major [1:20]

rec. 26 October 1937, EMI Studio No. 3, Abbey Road, London

Johann Sebastian BACH

(1685-1750) (arr. Cortot)

Concerto in D minor, BWV 596 (after Vivaldi Concerto Op.

3, No. 11) [9:57]

rec. 18 May 1937, EMI Studio No. 3, Abbey Road, London

Arioso (Arrangement of Largo from Concerto

in F minor, BWV 1056) [3:05]

rec. 18 May 1937, EMI Studio No. 3, Abbey Road, London

Felix MENDELSSOHN (1809-1847)

Variations Sérieuses, Op. 54 (1841) [10:46]

Song Without Words in E, Op. 19, No. 1 (from Bk.1, (1825-45) [3:32]

rec. 19 May 1937, EMI Studio No. 3, Abbey Road, London

César FRANCK (1822-1890)

Prélude, Chorale and Fugue (1884) [17:11]

rec. 6, 19 March 1929, Small Queen’s Hall, London

Mats. Cc 15975/78; Cat. DB 1299/1300

Prélude, Aria and Finale (1886-87) [20:54]

rec. 8 March 1932, EMI Studio No. 3, Abbey Road, London

Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835-1921)

Étude en forme de Valse, Op. 52, No. 6 (1877) [4:32]

rec. 13 May 1931, Small Queen’s Hall, London

Alfred Cortot (piano)

Alfred Cortot (piano)

rec. see listing for details.

NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.111381 [75:47]

NAXOS HISTORICAL 8.111381 [75:47]

|

|

|

Here is another rich vein of recordings from a bygone era, but

preserving some of the interpretations for which Alfred Cortot

became justly famous. The programme opens with some relatively

light repertoire. Purcell’s little dance tunes are a surprise

to find in recordings of this vintage, and it was the arranger

A.M. Henderson, a former pupil of Cortot, whose mission was

to create educational material and resurrect neglected work

so that they could be played on the piano. Cortot was in baroque

mood, having recorded the Bach transcriptions on this disc in

the same studio just a few months earlier. He presents Purcell

in an admirably playful and transparent style, unfussy but flexible,

teasing out the expressive character and dance mood of the pieces

without endowing them with unsuitable weight.

This is less true of the remarkable Concerto in D minor,

BWV 596 which Bach had transcribed from a concerto

by Vivaldi. As Jonathan Summers points out in his notes for

this CD, Cortot’s version sounds like an organ transcription

played on the piano, to the extent that some passages are actually

quite difficult to get a grip on. The introduction Praeludium

is particularly striking in this regard, the exploration

of variation over the pedal bass almost turning into an example

of lugubrious modern minimalism. Pounding bass and huge chord

textures bring us closer to Liszt or Busoni than Bach in this

performance, with even the expressive Sicilienne rich

in extra octaves in places. This is an impressive example of

Cortot’s pianism nonetheless, but revealing of the taste of

the period, and very much a recording of its time. The beautiful

Arioso which follows has a wonderful vocally expressive

melodic line and a restraint in the accompaniment which allows

the music to flow with elegance and freedom.

A day after the Bach recordings, Cortot was back for the two

Mendelssohn recordings on this disc. This is the first of three

he made of the Variations Sérieuses, Op. 54, and, while

not without its technical flaws, is still a marvellously intelligent

and expressively communicative recording. You can hear the stylistic

gears change as Cortot adjusts to Mendelssohn’s more contrapuntal

variations, the character of accompaniments lifting melodic

lines beyond mere tunes, the extremes of mood portrayed with

clear vision and almost tactile imaginative force. This would

have been the better of two takes, but without the benefits

of editing this has the feel more of a live performance than

a cosmetically perfect studio recording. I love the energy though,

and few pianists push the music this far to the outer edges

of its expressive limits. In this Cortot really is the father

of later greats like Horowitz.

Cortot’s recordings of César Franck stand as testimony to his

greatness as a performer of this composer’s music. The two recording

dates for the Prélude, Chorale and Fugue stem from an

intensive series of sessions recorded on a rich sounding Pleyel

piano in the Small Queen’s Hall in London. Along with a blistering

schedule of other repertoire, the work was recorded complete

on the 6th March 1929, and a number of re-takes were

done on the 19th. Cortot’s renowned sense of form

over the expanse of both of the Franck works is of course well

in evidence here, but it is equally interesting to divine the

ways in which Cortot is able to create atmosphere and perform

with a feel of genuine poetry. Despite the technical blemishes

which occasionally arise, there is a sense of balance and sensitivity

even where textures thicken and climaxes create genuine musical

storms. The same is true of the Prélude, Aria and Finale,

where lightness of touch holds at least part of the secret in

Cortot’s sympathy and effectiveness in Franck’s idiom. This

slightly later EMI recording has less surface noise but a more

nasal mid-range to the piano sound. The more clattery effect

where dynamics rise is less flattering to Cortot’s touch, but

it takes little effort to hear the inner contrasts and vocal

lines of phrasing which makes the performance stand out as a

true historical landmark. Especially the central Aria holds

the attention with its sense of magic, the feeling that the

music is being created on the spot – both improvisational and

controlled, and very much from the heart. The programme ends

with Saint-Saëns’ virtuoso show-stopper, the Étude en forme

de Valse, this recording of which should remove any doubt

one might have about Cortot’s technical abilities.

These early recordings do of course have their limitations,

but with excellent mastering by an un-named expert I was pleasantly

surprised at how good the sound was for artefacts of such a

vintage. Alfred Cortot looks out at us from the cover with frightening

intensity, and the recordings of Mendelssohn and especially

Franck reflect this stare, which seems to be able to penetrate

the soul and draw deepest from the creative wellsprings of each

composer. The squeaky-clean technical expectations of recordings

today are a considerable move away from the rough-hewn quality

of some moments in Cortot’s playing, but this takes nothing

from their historical significance. Anyone interested in the

timeline of pianistic history should be aware of Alfred Cortot,

and having his legacy spruced up and presented in Naxos’ Great

Pianists edition is a real treat.

Dominy Clements

|

|

|

All Nimbus reviews

All Nimbus reviews