|

|

|

Availability

CD & Download: Pristine Classical

|

Richard WAGNER (1813 - 1883)

Das Rheingold (1869)

Choir and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival/Clemens Krauss Choir and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival/Clemens Krauss

rec. live, in concert, Bayreuth Festival, 8 August 1953

Full cast details at end of review

PRISTINE AUDIO PACO039 [2 CDs: 145:15] PRISTINE AUDIO PACO039 [2 CDs: 145:15]

|

Availability

CD & Download: Pristine

Classical

|

Richard WAGNER (1813 -

1883)

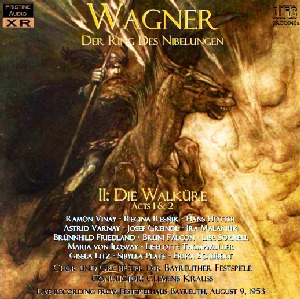

Die Walküre (1870)

Choir and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival/Clemens Krauss Choir and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival/Clemens Krauss

rec. live, in concert, Bayreuth Festival, 9 August 1953

Full cast details at end of review

PRISTINE AUDIO PACO040 [3 CDs:

210:55] PRISTINE AUDIO PACO040 [3 CDs:

210:55]  |

Availability

CD & Download: Pristine

Classical

|

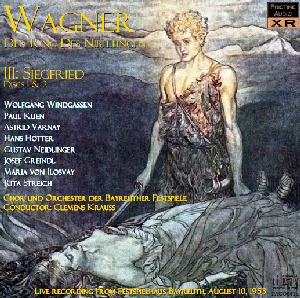

Richard

WAGNER (1813

- 1883)

Siegfried (1876)

Choir and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival/Clemens Krauss Choir and Orchestra of the Bayreuth Festival/Clemens Krauss

rec. live, in concert, Bayreuth Festival, 10 August 1953

Full cast details at end of review

PRISTINE AUDIO PACO041 [4

CDs: 242:11] PRISTINE AUDIO PACO041 [4

CDs: 242:11]  |

|

|

One “Ring” to rule them all? Well; maybe. It’s

a party game for Wagnerians without a winner; the big obstacle

to advocacy of this 1953 live

recording was always the dim, recessed sound of the orchestra. Those for whom

the “Ring” is primarily a music-drama for orchestra and voices have

always balked at the elevation of this set; those who first seek mighty Wagnerian

voices are to some degree blinded by the vocal quality of the stellar cast assembled

here and prepared to forgive those moments, such as when Donner gathers the mists

about him and strikes the rock with his hammer, when the impact of the orchestral

sound is sadly distant.

However, this enterprising remastering by Pristine Audio goes a long way towards

countering those objections and will for many permit this famous cycle to take

its place at the head of a long line, even if it is mono and can never rival

the “Sonicstage” splendours of John Culshaw’s Decca set. Pristine’s

sound engineer Andrew Rose understandably hesitated to undertake the task given

that Opera d’Oro/Allegro had already issued a beautifully packaged bargain

box-set of the whole thing - but this new incarnation leaves it in the dust,

sonically speaking. By comparison, the Opera d’Oro sound is cavernous and

bleary; Pristine have given it much more warmth, presence and definition. The

blare has been reduced and the all-important orchestral detail now emerges more

clearly. This improved sound has the effect of making the orchestra seem to play

better; on previous issues it could sound more like a high school band than the

same orchestra which the year before had been led to the heights in Wieland Wagner’s

new “Tristan und Isolde” under Karajan. There are still moments when

ensemble goes to pot - the “Ride of the Valkyries” is not its finest

hour - but we must remember that this is a live performance, with its pitfalls

and imperfections. It is also worth pointing out that it is not fair to judge

the sound quality of the whole cycle by “Das Rheingold”; although

it’s perfectly listenable. I am sure that by the second night the Decca

sound engineers had worked out better microphone placement and made the appropriate

adjustments to equipment sound-levels based on the experience of the first night’s

recording; there is a noticeable improvement in the sound of “Die Walküre” onwards.

At the time of reviewing, only the first three operas have been released by Pristine

but “Götterdämmerung” must be imminent - and I shall make

sure that I acquire it.

Apart from its inherent virtues, the legendary status of this production was

enhanced by the fact that its conductor, Clemens Krauss, was dead within nine

months. Krauss is today widely reviled for the fact that he is perceived as one

of the worst “Nazi collaborator” conductors - yet he and his wife,

the celebrated soprano Viorica Ursuleac collaborated with the Cook sisters to

smuggle Jews to safety in England. Leaving that aside, Krauss was clearly a skilled

Wagner practitioner who favoured a fleet, forward-moving pulse but also knew

how to give his singers space and to achieve the required stillness in the more

reflective moments of the drama. His approach is light-years away from the sturdy

Kapellmeister grind adopted by such as Knappertsbusch and to my mind far preferable.

My one serious disappointment lies in Krauss’s failure to generate enough

excitement at the end of Act 1 of “Die Walküre” when the explosive

passion of the incestuous twins is uncovered. He is rhythmically too slack here

and cannot emulate the inexorable drive of Bruno Walter in 1935 or Leinsdorf

in his neglected 1961 recording, but elsewhere, in general, Krauss sustains tension

admirably.

The cast is extraordinary; all the more so in an age bereft of Wagner singers.

Vinay’s effortful Siegmund, for all his musicality and burnished tone,

cannot be considered the equal of Walter’s Melchior but he is a fine actor

and has all the notes. Windgassen’s first essay as Siegfried is compromised

by his intermittently bleating tone, some pardonable slips and a characteristic,

infuriating anticipation of the beat in the forging scene. He is no-one’s

youthful ideal as Siegfried, but where is his like today? I admire Regina Resnik’s

impassioned Sieglinde although it has generally been considered a weakness. Astrid

Varnay, while not having the laser intensity of Nilsson, exhibits extraordinary

vocal commitment and stamina as Brünnhilde, some scooping apart. Josef Greindl

assumes three pivotal bass roles as Fafner, Hunding and Hagen, and is far steadier

than was sometimes the case; a proper German “black” bass to chill

the marrow. But for me, and for all the virtues of the other singers, the two

stars of this cycle are Gustav Neidlinger and Hans Hotter.

Neidlinger’s Alberich is a fully-formed assumption: malevolence

and despair incarnate, incredibly steady and incisive. He makes

a formidable adversary to Hotter’s Wotan.

The improved sound allows us to hear the slight wheeze in Hotter’s singing

no doubt attributable to his chronic hay fever, but for the most part the sonority

of his bass his awe-inspiring. I admit that I never “got” Hotter

before listening to this set but my impressions were gained from hearing him

recorded too late in the Solti cycle, when his tone had loosened and become “woofy”.

Here his authority and commanding vocalisation really do conjure up a god - yet

conversely he is humanity and tenderness incarnate in “Der Augen leuchtendes

Paar”; he inflects the text with the heart-breaking intensity of a seasoned

Lieder-singer.

Other famous names from the 1950s feature in even relatively minor supporting

roles. This consistency and strength of casting in combination with Krauss’s

alert direction have always endeared this “Ring” to Wagnerians but

this remastering by Pristine will be instrumental in encouraging a new generation

of “Ring” aficionados previously deterred by the primitive sound

to become acquainted with a great Bayreuth monument. It will not replace Solti

or Karajan for beauty of sound, but it is now the front-runner as a supplement.

Ralph Moore

Full cast lists

Das Rheingold

Wotan - Hans Hotter

Donner - Hermann Uhde

Froh - Gerhard Stolze

Loge - Erich Witte

Alberich - Gustav Neidlinger

Mime - Paul Kuen

Fasolt - Ludwig Weber

Fafner - Josef Greindl

Fricka - Ira Malaniuk

Freia - Bruni Falcon

Erda - Maria von Ilosvay

Woglinde - Erika Zimmermann

Wellgunde - Hetty Plümacher

Flosshilde - Gisela Litz

Die Walküre

Siegmund - Ramón Vinay

Sieglinde - Regina Resnik

Wotan - Hans Hotter

Brünnhilde - Astrid Varnay

Hunding - Josef Greindl

Fricka - Ira Malaniuk

Gerhilde - Brünnhild Friedland

Ortlinde - Bruni Falcon

Waltraute - Lise Sorrell

Schwertleite - Maria von Ilosvay

Helmwige - Liselotte Thomamüller

Siegrune - Gisela Litz

Grimgerde - Sibylla Plate

Rossweisse - Erika Schubert

Siegfried

Siegfried - Wolfgang Windgassen

Mime - Paul Kuen

Brünnhilde - Astrid Varnay

Wanderer - Hans Hotter

Alberich - Gustav Neidlinger

Fafner - Josef Greindl

Erda - Maria von Ilosvay

Waldvogel - Rita Streich

|

|