|

|

|

alternatively

CD: Crotchet

|

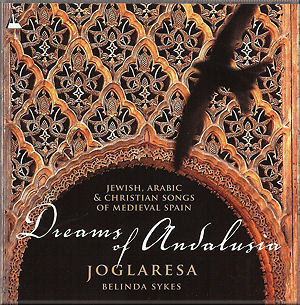

Dreams of Andalusia

Jadaka l-ghaithu’idha l-ghaithu hama [1:36]

Yahnikum, yahnikum [4:51]

Miyyah fi miyyah [7:25]

Macar ome per folia [8:17]

Por fol tenno quen na [3:00]

Al pasar por Casablanca [6:59]

Hal dara zabyu l-hima [2:39]

Estampida Instrumental [3:56]

Masha s-sahar hayran [3:27]

Ayyuha s-saqi ’ilay-ka l-mushtaka [7:20]

Como poden per sas culpas [3:07]

Jarriri l-dheila ’ayuma jarri [1:11]

A Sennor que mui ben soube [6:44]

Quen bõa dona querrá [3:33]

Joglaresa: Naziha Azzouz (voice),

Belinda Sykes (voice, shawm, bagpipes), Stuart Hall (oud, tar), Ben Davis (vielle),

Paul Clarvis (bendir, Andalusian tar), Tim

Garside (darabuka, Andalusian tar), Salah Dawson Miller (bendir, Andalusian tar);

Hilary Hazard, Lucy Gibson, Wendy March, Sonia Ritter (voice, on ‘A Sennor

que mui ben soube’ only. Joglaresa: Naziha Azzouz (voice),

Belinda Sykes (voice, shawm, bagpipes), Stuart Hall (oud, tar), Ben Davis (vielle),

Paul Clarvis (bendir, Andalusian tar), Tim

Garside (darabuka, Andalusian tar), Salah Dawson Miller (bendir, Andalusian tar);

Hilary Hazard, Lucy Gibson, Wendy March, Sonia Ritter (voice, on ‘A Sennor

que mui ben soube’ only.

rec. 27-29 January 2000, East Woodhay Church.

Texts and translations included.

METRONOME METCD1062 [64:10] METRONOME METCD1062 [64:10]  |

|

|

The learned Benedictine nun Hroswitha of Gandersheim (c.935-c.1002),

poet and

dramatist, described the Andalusia of her time as “the ornament of the

world”. She had never visited Andalusia, but had no need to do so to be

fully conscious of its reputation for scholarship and artistic creativity. And

for what, sadly, now seems a remarkable degree of religious tolerance and cultural

interaction. From the middle of the eighth century until the fifteenth, Islamic,

Christian and Jewish populations lived in relative harmony with one another.

Their various cultural traditions - in such matters as philosophy, mathematics

and science as well as in the arts and such arts of living as food and clothes

- coexisted in complex patterns of mutual influence. María Rosa Menocal

borrowed Hroswitha’s phrase for the title of her fascinating and accessible

book published in 2002: The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and

Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain. It is the musical

dimension of this ‘ornament of the world’ that Belinda Sykes and

Joglaresa explore on this CD, recorded as long ago as January 2000 but only now

released.

Belinda Sykes, director of Joglaresa and the musical mind behind this anthology,

certainly approaches the repertoire of the period in the spirit of cultural interaction.

The emphasis is upon the strophic song with a refrain (a model which spread throughout

Europe from Andalusia), which existed in two major verse forms, the muwashshah (written

in classical Arabic) and the zajal (written in an Arabic dialect peculiar

to Andalusia). Although a healthy selection of poetic texts of such songs survive

in Arabic, as do texts for the Hebrew and Christian songs (such as the famous Cantigas

de Santa Maria), we have far fewer musical records where the Arabic and Hebrew

songs are concerned. To make possible the performance of such Arabic texts, Sykes

and her colleagues have sometimes resorted to fitting the text to a surviving

medieval Christian melody or to a traditional Arab-Andalusian melody; elsewhere

they make use of a traditional melody to which the particular text is still sung

(and which may, conceivably, be a direct descendant of the original melody);

sometimes they rely upon improvisation within the conventions of such medieval

Arab-Andalusian music as we do have.

The results are generally very impressive. With plenty of percussion, with some

fiercely reedy instrumental accompaniment and some fine work on the oud and the

vielle - plus, of course, the voices of Naziha Azzouz and Belinda Sykes herself,

powerful but capable of appropriate subtlety - these songs communicate their

sentiments vigorously and the performances are never short of energy. For the

most part only a single pitched instrument is used at any one time, and this

allows a degree of intimacy and freedom in the interplay between voice(s) and

melodic accompaniment, both supported by the hyperactive (but never over-fussy)

percussion section. There would, of course, be plenty of room for scholarly debate

about the ‘authenticity’ of much that can be heard on this CD. But

these are performances that have (irrespective of any such debate) their own

kind of authenticity, their own truth to human emotion, to musical intuition

and (where the resources exist) to scholarly information. Belinda Sykes is both

an experienced performer in a range of musical traditions and Professor of Medieval

Song at Trinity College of Music. Were she only the one or the other - intuitive

performer or scholar - the performances would undoubtedly be rather less satisfying

than they are. The sung texts here vary from the praise of the Virgin Mary to

the celebration of the “love’s intoxication” and Joglaresa

find apt language for these and for many other sentiments. Sometimes the fusion

of sources strikes unexpected sparks; so, for example, the text of a poem by

Ibn Quzman of Cordoba (c.1080-1160) is sung to a traditional Algerian melody

and in a rhythmic mode taken from the folk music of the Maghreb; or, to take

another example, a poem by Don Todros Abulafia of Castile (1247-1306) is sung

to the melody of one of the Cantigas de Santa Maria (No.40) - the text

of the Arabic poem is a woman’s praise of her lover’s character,

that of the Christian song it ‘replaces’ is a hymn in praise of the

Virgin. Time and again, these performers make such combinations work, as they

effect their own kind of convivencia.

The recorded sound is good and does justice to the fascinating percussive textures

that distinguish so much in the programme. The motif of cultural interplay and

layering is nicely enhanced by the fact that this recording was made in the late

Georgian church of St. Martin of Tours in East Woodhay.

Glyn Pursglove

|

|