Julius Harrison &

Bredon Hill

It is almost impossible

to discover what inspired a composer

to write a piece of music in a particular

style - especially when this style would

appear to be virtually unique in the

composer's catalogue. It has to be stated

at the outset that 'Bredon Hill -

a rhapsody for violin and orchestra'

is a 'retro' work. This work does not

easily fit into any categories of music

that may have been 'in the air' in the

early nineteen-forties. It certainly

is not modernist or avant-garde in any

way whatsoever. In fact the piece has

probably suffered a dearth of performances

simply because it was well out of kilter

with the prevailing post-war musical

aesthetic.

Furthermore, this work

was not typical of the composer himself.

Brahms, Bach, Verdi and Bantock were

the composers who seemed to inspire

most of Julius Harrison's work: it was

rarely the folksong school or the 'back to the Tudors' enthusiasts.

But the other side

of the coin is important too. It would

be all too easy to condemn Bredon

Hill as 'pastoral' or 'bucolic'. A cynic could see a field

of cows, some leaning over the fence. At first hearing the obvious

inspiration appears to be Ralph Vaughan Williams' The Lark

Ascending. However an over-simplistic

equation of the two works would be wrong.

This work is not a succession of folk-inspired

tunes hung together with a few modal

scales and arpeggios for a rusticated

soloist.

Julius Harrison was

born at Stourport in Worcestershire

on 26 March 1885. He was to die at Harpenden

on 5 April 1963. Grove's Dictionary

notes that he studied with Granville

Bantock at the Birmingham and Midland

Institute of Music. He studied conducting

and was soon deemed competent enough

to be sent to Paris by the Covent Garden

Syndicate to rehearse Wagner operas

with Nikisch and Weingartner. It is

as an opera conductor that he secured

his reputation. He spent time working

with the Beecham Opera Company and the

British National Opera Company. However

it was his appointment to the Hastings

Municipal Orchestra that allowed him

to exercise his authority: he was able

to raise the standards of this orchestra

to the same level as that at Bournemouth.

However, he slowly succumbed to deafness

and after the disbandment of the HMO

he was able to concentrate on composition.

His greatest works

are the Mass in C minor at which

he laboured for eleven years and the

Requiem (1948-1957). Geoffrey

Self notes that these huge works are

influenced by Wagner and Verdi and are

'conservative and contrapuntally complex

pieces'. They remain unheard in our

generation.

Julius Harrison became Director of Music at

Malvern College during the autumn of 1940. As already noted, he

had previously been Director of Music to the Hastings Corporation.

He had wrought splendid changes at the White Rock Pavilion in that

seaside town. Harrison had worked with some surprisingly great

artists including Rachmaninov, Beecham and Paderewski. He

encouraged the local Choral Union and regularly gave performances

of Beethoven's

Ninth Symphony. Sadly, some months

after the Second World War broke out,

the town corporation decided to disband

the orchestra. At that time Hastings,

as an English Channel resort, was literally

on the front-line.

The move back to the

Midlands and the college directorship

turned out to be successful for the

composer: he was able to recover thoughts

and memories of his younger days. Harrison

told the author Donald Brook that he

was "very much affected by the

beauty of our Worcestershire countryside,

and by its close association with some

of the great events in our national

history." He continued, "...to

me, as with many other Worcestershire

folk, this county seems to be the very

Heart of England, and there is a song

and a melody in each one of its lovely

hills, valleys, meadows and brooks."

The present work was, in many ways inspired

by this countryside. As a matter of

fact Julius Harrison could see Bredon

Hill from his bedroom window. Yet this

is not the full story.

There are three 'versions'

of the genesis of Bredon Hill.

The first is the simplest. Soon after

arriving at his new house in Pickersleigh

Road, Malvern he was filled with an

overwhelming desire to celebrate in

music some of the thoughts and emotions

behind A.E. Housman's great and tragic

poem, 'In summertime on Bredon'. No

doubt the composer had known this poem

for many years and it would often cross

his mind as he looked across to the

hill.

The second version is related by Lewis Foreman

in the sleeve notes for the premiere recording (see below for

details). Foreman relates that Julius and Dorothie, his wife, met

a local Malvern school mistress by the name of Winifred Burrows.

One day she took them to Bredon Hill by motor car with the aim of

seeing the sun setting in the West - over the Malverns.

This particular event moved Harrison

to write this work and quite naturally

the composer dedicated the new piece

to Miss Burrows.

A third possibility is also alluded to by

Foreman. During the war years Elizabeth Poston was Director of

European Music at the BBC. Poston was very much an all-round

musician: she was a composer, musicologist, arranger,

administrator and a performer. She played the piano - most notably

at the wartime National Gallery lunchtime concerts. She edited and

arranged carols and songs and wrote a large number of programme

notes for the Arts Council. But it is as a composer that she

should be best known. Poston composed a surprising amount of

incidental music for radio and TV which by nature tends to be

ephemeral. A moderate catalogue of works includes some two dozen

songs, many carols and part songs and even an operetta - The

Briery Bush. However it is her instrumental

music that urgently requires revaluation:

this includes a considerable Sonata

for Violin and Piano.

It was in her role

at the BBC that she corresponded with

Julius Harrison. Foreman admits that

it is now not possible to know if Poston

actually commissioned Bredon Hill

for performance by the BBC or whether

she simply became aware that Harrison

was working on the score. In either

case the work was taken up by the BBC

and was broadcast extensively.

However, whatever the motivation, the

fundamental inspiration was the Hill itself - this landmark

so beloved by poets and musicians, including

Herbert Howells, Ivor Gurney and Ralph

Vaughan Williams. Of course, the landmark

was originally put onto the intellectual

map by A.E. Housman. Perversely there

is an interesting school of thought

that suggests that Housman was hardly

intimate with Bredon Hill and its surrounding

countryside! Most enthusiasts of British

music will know at least a couple of

settings of 'Summertime on Bredon'.

One need only think of the song cycle

On Wenlock Edge by Ralph Vaughan

Williams or Bredon Hill and other

Songs by George Butterworth.

Yet it would be wrong

to draw some kind of simplistic line

from poet to composer in this case.

For the poetry of Housman is not always

as it seems. On first reading many of

his poems appear to be taken up with

images of nature and brief descriptions

of places. However the bottom line of

so much of his poetry is that his images

must be seen as metaphors of passing

- of death. It is small wonder that

'The Shropshire Lad' gained much currency

during the slaughter of the Great War.

Housman created a place of the imagination - an idealised land,

somewhere 'out west' - a 'far country'.

It was a land of strong farm labourers

living a bucolic life - playing football,

roistering and seemingly indulging in

homo-erotic fantasies. In this unreal

'Land of Lost Content' the poet insisted

that happiness may once have held sway,

but the realities of life had caused

this sense of well-being to evaporate.

There is always bitter-sweetness and

a sense of what might have been in Housman's

poetry.

Of course these poems

have been interpreted widely and in

contrasting ways by the many composers

who have set Housman's texts. Barbara

Docherty has analysed a number of settings.

Arthur Somervell, for example tended

towards 'unfocused geniality' that passed

over any long term pain. Butterworth

is better able to evoke the 'dreamy streams and the idyllic

summers' and

the 'reality that was about to shatter it'. It is a fact that not all composers

have managed to define in their music

Housman's bottom line - which is a depressing

belief in a reasonable life constantly

subject to thoughts and intimations

of inevitable pain and loss and death.

Even a superficial hearing of Julius Harrison's Bredon

Hill does not reveal such depression

and black moods. There are no real musical

references to the tragedy that 'Summertime on Bredon' describes. The bride to be

is not laid low by illness. There is

no tragic outburst of the lover demanding

that the 'noisy bells be dumb'.

The most famous and

certainly most evocative words from

this poem are:-

Here of a

Sunday morning

My love and

I would lie

And see the

coloured counties

Above us in

the sky.

Appropriately it is

with this quotation that Julius Harrison

prefaced his score.

The starting point

for Harrison is quite simply the verse

quoted. It is a meditation on the 'coloured

counties'. The progress of the music

points up 'all the live murmur of a

summer's day' as well as the poignancy

of a sunset over the Malverns. It is

an idyllic world that seems to have

no major terrors or fears. It is the

'Western Playland' writ large. The lover

and his bride do get to the church and

they do seal their union - at least

in theory.

Now, this is not to

say that the music does not have tensions

and stresses or to suggest that the

work is consistently banal. There are

definitely a number of reflective moments:

there are bars that show a certain wistfulness.

On occasion passion does dominate for

a few moments. But taken in the round

Bredon Hill is definitely more

happy than sad: it is positive rather

than negative and Janus-like it looks

both back into an idyllic past and forward

to what should have been a better

future.

At this time the BBC

had a campaign to promote things 'British'.

Foreman notes that this was to present

an idealised, idyllic view of England.

This may have been especially aimed

at British citizens who were at that

time living abroad. Or maybe it was

supposed to remind the military and

the Home Front of one of the many reasons

why they were fighting the war? But,

without being cynical, the bottom line

was that it was better for the war effort

to present the green fields and the

purling streams and thatched cottages

rather than the slums of Manchester

or the mean streets of Glasgow or the

industrial pollution of West Yorkshire.

To further point up

this bucolic impression the BBC had

recorded a 'scripted' discussion between Harrison and Poston.

The BBC announcer prefaced this debate with the following glowing

plug - "[It is] one of the loveliest works of the year-indeed, I

would go as far to say - of our own

time...[it] was completed by the composer

with a view to its special appearance

in the Music of Britain [series]. It

is a fact remarkable in itself that

such music as this comes out of the

present time. That it does, is perhaps

the best witness to the eternal spirit

of England."

The 'on-air' discussion

with Poston ended with Julius Harrison

recalling how the work "grew out

of itself in my mind from all those

scenes I have known all my life. After

all we must not forget that this part

of Worcestershire speaks of England

at its oldest. It is the heart of Mercia,

the country of Piers Plowman, and is

the spirit of Elgar's music too."

The controversial authors

of 'The English Musical Renaissance 1840-1940' give nearly half a page of

text to Julius Harrison. They simplistically

state that Harrison based his piece

on Housman's poem and was redolent of

folksong. It leaves me wondering if

they had actually heard the work. Yet

their concluding words are apposite

to the genesis of this piece. They write:

- "But if the lark was once again

ascendant, the air it hovered in was

no longer clear. Recumbent lovers on

the English Down heard the dull drone

of the bomber fleets and witnessed the

dogfights of a struggle for national

survival." [p.200]

And I think that this

presents the basic dichotomy presented

by this work. On the one hand it is

a pleasant and approachable rhapsody,

whereas on the other it is a deeply

thoughtful works that was specially

designed to raise thoughts of England's

green and pleasant land, along with

its sterling history in the mind of

listeners. Beside this some of Housman's

melancholy does rub off. Not all hearers

would be able to realise this dream:

not all would return to England 'after the war'.

The most obvious exemplar

of all 'pastoral' music, including Bredon

Hill was Ralph Vaughan Williams'

The Lark Ascending. This work

was first heard post-Great War in 1922

and is based on a poem of the same title

by George Meredith. Meredith's poem

begins with the words "He rises and

begins to round/He drops the silver

chain of sound."

However it is important

to note that this piece had in fact

been sketched out before the commencement

of hostilities, the work that is known

today is a revision made in 1920. This

is a pastoral composition. The

Lark is largely untroubled by the changes

and chances of life. The trenches of

the Western Front do not feature in

this landscape.

One of the fundamental questions about Julius

Harrison's Bredon

Hill is as to its status as an example

of the 'English Pastoral School'. Geoffrey

Self points out that Bredon Hill

is more akin to a concerto movement rather than a tone poem. He

regrets that the complete work never existed. Apparently Harrison

had considered writing such a concerto and had completed a number

of sketches ' according to his

wife he had carried "such a work in his head for a number of

years".

It is inevitable that

a work inspired by one of the purple

passages from one of the best known

poems by Housman would lead to a 'pastoral'

work. In fact the general tenor of contemporary

critiques lies in this direction. But

was it a pastoral work? Would Constant

Lambert have thought of fields and gates

and cows?

I have already noted

that one of the possible exemplars of

this work is The Lark Ascending.

However it necessary to avoid jumping

to conclusions based on certain similarities

and to ignore the differences.

English Pastoral

can be quite difficult to define. Ted Perkins in a web

article has suggested three possible stylistic markers 1) Use of

folksong/modal inspired melody, 2) impressionistic techniques and

finally 3) a certain neo-classical colouring. Ironically he uses

Vaughan Williams'

Oboe Concerto rather than his Lark

Ascending as a fine example of this

style. Popular opinion would suggest

that any music that is gentle and reflective

would be labelled 'pastoral' yet Perkins

argues against this view.

On first consideration

Bredon Hill seems to fit the

criteria of 'pastoral'. All three criteria

are generally or momentarily present.

Yet there are deeper waters here.

Although on face value the work nods to Vaughan

Williams it is Beethoven's Romance for Violin

and Orchestra in F major that is

the true exemplar. This is not to suggest

that this is a classically inspired

work, yet it is important to emphasise

that I do not believe that it is in

any way a 'tone poem'. It is certainly

not a 'rhapsody' on folk tunes - original

or confection. The Beethoven Romances

were thought to have been composed between

1798 and 1802. It is difficult to know

which of the two were written first

although the Romance in G major

was published first in 1803 and the

F major in 1805. In a strange

parallel to Bredon Hill, it is

thought that the Romances may

have been intended as alternative slow

movements for the (presumably) unfinished

Violin Concerto in C major of

1790-1792. Yet these slow movements

are not in the 'traditional' ternary

form. They are in fact slow rondos with

two episodes.

Now there is little

mileage in suggesting that the G

major is a model for Bredon Hill

- it is too light-weight.

Yet it is a different matter when one

considers the F major. This is

a dramatic and quite impassioned work

that certainly goes beyond any banal

idea of a 'romance'. I do not suggest

that Harrison consciously used the score

of the Beethoven as a model. Yet one

cannot help feeling that his experiences

as a conductor at Hastings and elsewhere

would have made him familiar with Beethoven

in general and this Romance in

particular.

There is a similarity in mood and emotion in

these two works that bears comparison - although I feel

that the Beethoven has a little more

stress and tension in many of its pages.

Furthermore the formal basis of Harrison's

work is more akin to a slow rondo than

anything else. The F major Romance

was described to me by a musicologist as if the composer was

sitting by himself, having happy thoughts and sad thoughts and

hopes for the future. However the overall mood of both pieces of

music is the fear of loss - something is about

to disappear. It may be the calm before

the storm. Will the composer's hopes

be brought to nothing? Not if he and

the rest of humanity can pull together.

Three or four quiet

chords from the orchestra begin this

'slow movement'. But immediately the soloist makes his presence

felt. The violin begins its soaring song as it means to continue.

At first it is to the fore with a light but quite subtle

orchestral accompaniment. A sudden rise to the higher register

leads to one of a number of cadenzas - soon collapsing to a dead

stop. After the briefest of pauses the soloist begins his task of

contemplation on the key (rondo) theme. The support from the

orchestra begins to build up - there is much more dialogue here.

Yet the original mood is still apparent. A surge of passion leads

to the first climax which is perfectly understated. The violin is

always prominent with it reflections and commentary on the musical

material. This is definitely not a folk tune: it is timeless music

that cannot help bringing to mind Vaughan Williams - not in this case the Lark

Ascending but the last movement

of the Pastoral Symphony.

There is an unexpected burst of intensity from

the orchestra just before the half way point - but

the violin continues its song, it is

never put off. This soon begins to rise

to the main climax of the piece. This

positive, swelling music seems to me

to blow from a different place than

Bredon Hill - perhaps from the depth

of Harrison's heart? Some fine double-stopping

leads into another short cadenza followed

by a restatement of the main theme.

Quicker music follows for the woodwind and the

soloist - in fact contrapuntal themes seem to play with each other

for a few bars. However the pace slows before the composer

restates the glorious tune - first by the soloist

and then by the full orchestra. Now

the music calms down and becomes reflective

again. There is a restatement of the

main theme and a little cadenza. We

feel we are in the closing pages now.

The woodwind play a little pastoral

tune that is taken up by the strings.

We hear 'muffled horns' and the bells

of Bredon Hill playing in the orchestra

before the soloist closes the work with

a little phrase in the lower register.

The hill is left in peace.

The work is scored

for double woodwind, four horns, two

trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani

and string. It was published by Hawkes

in 1942. A reduction for violin and

piano was subsequently produced.

The first performance

was given in a BBC Studio concert on

29 August 1941 with Thomas Matthews

as the soloist, the composer conducting.

However it was widely performed throughout

the world, being broadcast on successive

nights in North America, Africa and

the Pacific. After the first flurry

of enthusiasm for this work the number

of performances seemed to decline rapidly.

As a piece it certainly did not fit

into the tastes and aspirations of post-war

music.

'Tempo' described this

work as a "notable addition to the brief

list of short works for violin

and orchestra". The Musical Times was

more fulsome in its praise: - in an

anonymous review of the first broadcast

performance, the writer states that

Bredon Hill is "one of the

sweetest additions to music with our

own country's sap and surety in it.

No composer now more genially evokes

a testament of things felt and prized,

things true for all of us, about England". Fulsome praise indeed

- and yet praise

that would be laughed to scorn in current

lack of confidence in things English.

'Music and Letters'

suggests that the work "spills

over with but semi-controlled emotion..."

However, the reviewer goes on to suggest

that a little of Mr Reizenstein's (also

performed at the same concert) dryness

and objectivity could have been infused

into it [Bredon Hill]. He questions

whether Harrison has sufficient material

to expand into a twelve minute work

and suggests that interest and attention

could be lost. However 'EB's' comments

are not all negative. He recognises

that the writing for "both soloist and

orchestra is always luminous and to

the point". He even allows that a number

of poetic touches illuminate this work. But the proof is in the

pudding and in the last sentence - "It should

prove a well liked work."

In 1951 a performance

of Bredon Hill was broadcast from the Winter Gardens in

Malvern along with Arnold Cooke's Concerto for

Strings and Sir Edward Elgar's 1st

Symphony. However the reviewer in

The Times points out that "it was a far cry from this music

(Cooke) to the other contemporary work in the programme".

David Wise was the soloist along with

the LPO. The 'special correspondent'

continued enthusiastically, "...its

gentle, ruminative poetry showed scarcely

less than with the Elgar how the atmosphere

of a landscape can shape the contours

of a composer's thought." Perhaps

the reviewer had in mind the oft-told

tale of Elgar listening to what the

reeds in the River Severn told him.

But I am a little concerned that there

may be a sting in the tail. Surely the

'ruminative' noted above suggests a

ruminant which may suggest a cow leaning

over a gate?

In 1985 Kenneth Loveland

notes that the 100th anniversary

of the composer's birth attracted little

notice. However the present work was

appropriately performed at Hereford

Cathedral and appeared to be well received.

Loveland was impressed that Three Choirs

Town remembered Harrison and Bredon

Hill. The piece was apparently well

played by violinist Felix Kok. His final

comment recognises Harrison was no mean

composer and conductor.

Most recently Dutton

Epoch has released a CD of music dedicated

to Harrison's orchestral music. It remains

to be seen what the critical reception

of this recording will be. However this

author is generally impressed by the

attractiveness, the craftsmanship and

the integrity of all this music.

Bredon Hill

is an important work from a number of

points of view. Firstly it is a well

crafted rhapsody for violin and orchestra

that is enjoyable to listen to and grateful

to play. Secondly it is a fine example

of a work that is nominally in the 'English Pastoral' school of composition but

goes beyond the 'play it once, play it again, louder' critique of Constant

Lambert. But thirdly the work ranges

well beyond this limited genre to something

rising out of the deep springs of the

traditional classical and romantic music

of previous generations.

Lewis Foreman quotes

Gordon Bottomley on this work, "The

dew was so fresh and undimmed by footsteps.

Some of the harmonies came from further

off than Bredon: perhaps there had been

footsteps on them that did not show

on the dew."

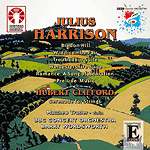

Discography

Julius Harrison

Orchestral Music: Bredon Hill, Widdicombe

Fair, Troubadour Suite, Worcestershire

Suite, Prelude Music and Romance: A

Song of Adoration. Also Hubert Clifford:

Serenade for Strings.

Matthew Trussler (violin).

BBC Concert Orchestra conducted by

Barry Wordsworth.

Dutton Epoch CDLX 7174

Select Bibliography

Articles in Grove.

Donald Brook: Conductors Gallery

Rockcliff, London 1946

Barbara Docherty: English

Song and the German Lied 1904-34

Tempo, New Ser., No. 161/162

1987 pp.75-83.

Lewis Foreman: Sleeve notes to Dutton

Epoch CDLX 7174.

Ted Perkins Pastoral

Style and the Oboe

Geoffrey Self: Julius Harrison and

the Importunate Muse London 1993

Meirion Hughes and Robert Stradling:

The English Musical Renaissance, 1840-1940

University of British Columbia Press.

2001 [2nd edition]

Notices from Tempo, Musical Times etc.

John France, 2007 Ó