There are lots of new

record labels about, but Explore Records

is special. They focus on important

recordings that haven’t made the transfer

to CD. For the first time in years,

we’ll be able to get hold of this material

without having to track down playable

LPs (or LP players). Fortunately, Musicweb

can supply their catalogue.

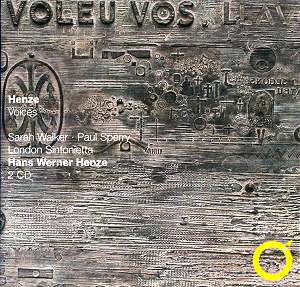

This release is the

premiere recording of Hans Werner Henze’s

Voices. It’s conducted by the

composer himself, and performed by the

London Sinfonietta, for whom it was

written. This alone would make it a

must-hear, but on its own merits it

is by far the most lucid and idiomatic

performance. For years I’ve praised

the only other worthwhile version, conducted

by Horst Neumann in Leipzig, also from

1978/9 with Roswitha Trexler and Joachim

Vogt. It’s on the Classics label but

there’s also one conducted by Johannes

Kalitzke on CPO 999 192. But a friend

said this version was by far better.

He’s absolutely right. While the Neumann

reflects the older German agitprop tradition,

this version is far more modern, much

more in tune with Henze’s essential

new music and international outlook.

This year (2006), the work was performed

at the Proms review

and some critics dismissed it, suggesting

that it was dated. If only they’d heard

this livelier version! This performance

is spirited and vivacious, and the music

is as fresh, and as relevant, as the

day it was written. If all releases

by Explore are as good as this, we are

in for exciting times.

Voices is a

kaleidoscope of songs from different

genres, expressing Henze’s belief in

the fundamental unity of the "people"

of the world. Unlike, say, Tan Dun,

Henze doesn’t attempt to adapt non-western

music into his own, because no outsider

can really assimilate forms which have

evolved over centuries. He sticks to

what a westerner might relate to, such

as North and Latin American idioms.

Instead, he minimalises his writing,

creating understated, unobtrusive settings,

giving the text prominence. Thus we

have the powerful "voice"

of Ho Chi Minh’s Prison Song,

unadulterated by pseudo-orientalism.

The only exotic touch here is the simple,

reedy flute melody, which could belong

in any Third World culture.

Nonetheless, where

it helps, Henze incorporates styles

that extend the impact of his songs.

His many years of living in Italy have

informed his writing style, so he adapts

Italian folk idioms with ease. Caino

is a song from the Italian wartime

Resistance. The poem is about a German

soldier, lying dead by a stream, his

hair flowing in the current like a "soft

weed". Flute, guitar and accordion

provide a minimal, but plaintive background,

as winding and limpid as the stream.

Sarah Walker’s voice captures the pathos,

but there’s no mistaking, when she sings

"Perchè, soldato tedesco?",

that this is a powerful anti-war statement,

even though it sympathises with a dead

enemy. The notorious Electric Cop

isn’t fake Americana so much as a savage

collage of images from television and

bad movies. It is a song which can easily

descend into embarrassing corniness.

Until now, it was my least favourite

in the set. I’d fast forward when it

came on. However, this performance has

made me realize just how coherent it

is, musically and conceptually. Henze

puts in gunshots and a tape of a political

rally, not for mere effect, but because

he’s building up a dense collage showing

how we’re assaulted constantly by mindless

sound. Paul Sperry’s singing shows how

carefully Henze has caught the idiomatic,

broken lines of the poem. The flamboyant

Hispanic ending suddenly makes sense.

It’s joyful dance, complete with maracas

and horns, coherently expresses something

real, unlike the barrage of sound that’s

come earlier. Having Henze conduct probably

made all the difference to this masterful

interpretation.

Ultimately, Henze’s

panorama is a vision of all humanity,

despite the vignettes of America, Italy

or Germany. Tellingly, one of the most

passionate performances is Sperry’s

account of the murder of 42 schoolchildren.

During the Vietnam war "What

have we learned", he intones

ominously, "From Guernica and

from Poland. From Coventry, Stalingrad,

Dresden, Nagasaki, Suez, Salkiet?".

I first heard this song in a film about

Voices, where images of bombs

and maimed children filled the screen.

The impact was such that I’ve never

forgotten it, nor recaptured the impact

from other performances. On this disc

though, it’s overwhelming. Although

I can’t be sure, I vaguely remember

that this was the recording used in

the film. Chances are, it was. This

version is truly visceral.

Voices was written

to capitalize on the London Sinfonietta’s

formidable strengths, their chamber

sensitivity and their fluency with unusual

instruments. Henze uses two or three

solo instruments in groups, creating

textures which shift weightlessly as

one group gives way to another. The

double bass frequently provides an anchor

holding lines together – there’s almost

no drumming, and even the brass is played

with restraint. . Sometimes, the musicians

have to hum, their very voices expanding

the human aspect of orchestration. This

humane quality is supported by the use

of instruments like accordion, harmonica,

mandolin and recorder, all humble instruments

that don’t need virtuoso players per

se. When played as sensitively in

ensemble as this, they become compelling.

For example, in the song The Worker,

a man is killed in an industrial accident.

The machines don’t stop, but continue

"whirling and buzzing and humming".

This is evoked in the accompaniment,

literally hummed by the orchestra, sounding

at once like machines and like a strange

church choir. The man may be humble

but the song makes him noble. The Sinfonietta

is infinitely better suited to this

music than Neumann’s East German orchestra.

There really is no comparison. They

are in an altogether different league.

The Sinfonietta is perhaps one of the

most important new music ensembles in

the world. The avant-garde is the natural

element in which they thrive. In their

hands, Voices comes alive, vibrant

with inventiveness and fluency. In this

case, being conducted by Henze himself

– no mean conductor, despite his pre

eminence as a composer – must have been

inspiring. There’s a real sense here

that all are working together towards

the same vision. The enthusiasm is infectious

– it’s hard to imagine anyone thinking

this version of Voices is dull.

The soloists, Paul

Sperry and Sarah Walker are superb.

This isn’t music for conservatoire voices,

since it’s supposed to reflect the common

man. There’s no need to belt things

out like Lotte Lenya – Henze’s music

is just too sophisticated and subtle

for that treatment. Trexler and Vogt

were influenced by their understanding

of the German tradition of political

cabaret which stresses direct communication.

Thus their approach has validity. Sperry

and Walker, however, are far more focused

on the modern aspects of the music.

Henze may have roots in the German tradition,

but he goes further musically than Weill

or Eisler could ever have imagined.

Thus Walker understands the inner dynamic

of Screams (Interlude). There’s

more to it than just screaming. She

has a feel for phrasing and the variation

of nuance, making sense of the way the

music shapes the poems’ fractured images.

Like some of the other poems in this

set it’s not very good, but what Henze

does with it makes it a work of art,

and Walker shows us how. Walker is a

much under-appreciated musician, whose

down-to-earth commonsense and sense

of humour allow her to approach this

most esoteric group of songs and bring

out their simple humanity. Her voice

moves from warmth to anguish, yet never

loses its flexibility and sense of conviction.

These are not easy songs by any means,

and being one of the first interpreters,

she had to understand them from within.

Paul Sperry is extremely

good, too. In Vermutung über

Hessen, he curls his voice around

the devious syntax "gutgläubige

falten die Finger inning um Knüppel

jetzt". It’s a miniature tour

de force, for he sings against a cacophonic

background of sounds imitating machines

and the sound of a loud hailer addressing

a crowd and police whistles. Yet the

ebb and flow of this song is important

– it veers between wild marches and

ironic detachment. Again, a sense of

irony brings out the true savagery of

these texts. In Schluss, the

orchestra imitates something between

an oompah band and a bouzouki troupe,

but Sperry’s singing makes clear that

the nihilistic message is anything but

complacent. Together, Walker and Sperry

are very good indeed too, for the key

duets, Das wirkliche Messer and

Das Blumenfest, depend on a complex

intertwining of their voices.

These last few weeks,

I’ve been blessed by a surfeit of excellent

recordings and can hardly believe my

good luck. But this recording really

is special. We are all lucky that Explore

has made it readily available at last.

Anne Ozorio