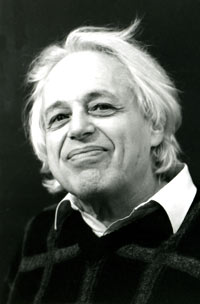

György Ligeti (1923-2006): an

obituary

With the passing of György Ligeti on

12 June 2006 at the age of 83 in Vienna

following a lengthy illness, the musical

world has lost a true maverick. An independent

thinker, Ligeti charted a singular route

in his music with the evolution of a

voice that is hard to ignore. In this

respect one is tempted to put him alongside

figures such as Boulez, Cage, Stockhausen

and Xenakis when considering the major

shapers of late twentieth century composition.

Ligeti was born in Romanian Transylvania

in 1923 to Hungarian parents. Musical

studies began in 1941 with his attending

Cluj conservatoire in Romania, which

led to further study at the Franz Liszt

Academy in Budapest, where he was later

appointed Professor.

Following his arrest in 1943, as a result

of being Jewish, Ligeti was sentenced

to forced labour for the remainder of

World War Two. Survival, however, was

not without its cost: the war claimed

his brother and father amongst other

members of his family.

The end of the war might have brought

physical release but musically he continued

to be heavily constrained by the Stalinist

censorship in Hungary. For this reason

much of his early work draws heavily

on the use of Hungarian and Romanian

folksong, reflecting the influence of

Bartók and Kodály. “I am an enemy of

ideologies in the arts. Totalitarian

regimes do not like dissonances”, he

commented ruefully. The Concerto

Romaneşc (1951) is composed

on the very limit of Stalinist dictates.

One can pick up the folk music influences:

Kodály in the dour Andantino, Bartók

in the scherzo and distant shades of

Enescu in the breathless finale.

After the 1956 Hungarian revolution

Ligeti fled to Vienna, and to his first

real contact with avant-garde composers

of the day, becoming an Austrian citizen

in 1967. The orchestral work Apparitions

established his reputation and secured

the important endorsement of Stockhausen

amongst others. From that point on Ligeti

rarely, if ever, looked back as a creative

force. Works such as Atmosphères

and Volumina expounded a personal

alternative to the serialism of Webern

and his followers. However, if there

was a single concern that dominated

his music it was change. No other contemporary

composer’s work is filled with so many

turning points. Some view these changes

as organic growth, taking its cue from

his research into chaos theory, fractal

geometry and biochemistry.

The 1960s saw his music consumed by

the use of super-dense polyphony he

called "micropolyphony". Poème

symphonique, written for 100 metronomes

which run down at different speeds,

is but a single example of this, and

in extreme. Parallels of a kind were

found in his use of speech sounds and

nonsense syllables, which – perhaps

unwittingly – can bring to mind the

Dadaist conception of language-music-construction

found in Kurt Schwitters’ Ursonata.

At the core of his artistic personality

is the quality of fun, and that in no

small measure has helped to make works

accessible to a wide public. Extracts

from Lux aeterna, Atmosphères

and Requiem found their way

into the soundtrack for Stanley Kubrick's

film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Kubrick was not one to choose his music

lightly, noting that Ligeti’s work had

“an extremely urgent visuality” about

it.

As if to consciously exploit populist

appeal (though I am sure he would not

have agreed with this view) his works

of the 1970s moved back to a whole-hearted

use of tonality. By way of justification

he stated unapologetically, “ I no longer

listen to rules on what is to be regarded

as modern and what as old-fashioned.”

This ran in parallel with several important

explorations of the concerto territory.

Musical “forms with history”, including

the étude (his proved to be the most

important recent contributions to the

genre) were now back on the agenda.

The Piano Concerto blends more

than other works elements of polyphony

and folk music. The Hamburg Concerto,

a horn concerto in all but name, sets

the soloist against instrumental groupings

including four natural horns to make

possible the exploitation of overtones.

The Violin Concerto recalls with

more than a little nostalgia his roots

and the style of folk fiddling with

intentionally varied tuning of the solo

instrument, to an unreservedly polyrhythmical

accompaniment. This reflects the growing

influence that African drumming was

having upon his music in the 1990s.

Surrealist juxtaposition and the theatre

of the absurd came to bear in equal

measure upon the inception of his stage

work Le Grand Macabre,

an effortless mix of operetta and the

darkest of black humour: “Stage action

and music should be dangerous and bizarre,

absolutely exaggerated, absolutely crazy.”

This, he felt, was the most direct way

he could reach an audience.

Among the many awards and prizes his

work attracted a couple stand out. The

2004Polar Music prize recognised his

ability to "stretch the boundaries

of the musically conceivable from mind-expanding

sounds to new astounding processes,

in a thoroughly personal style that

embodies both inquisitiveness and imagination

", as the judges put it. The same

year also brought the ECHO KLASSIK Award

given by the Deutsch Phono-Akademie

for Lifetime Achievement.

There can be little doubt that Ligeti

was fortunate in having musicians with

searching interpretive abilities perform

his music in recent years with Pierre-Laurent

Aimard, Isabelle Faust, Charlotte Hellekant,

Jonathan Nott, George Benjamin and the

Arditti Quartet amongst them. Without

the determination of such artists the

Ligeti Edition on record might never

have been achieved. Requiring several

labels that were willing to get involved

at various stages throughout the project,

more than once it seemed as if the end

might never be reached. How close Ligeti

came to being a major victim of the

recording industry’s collective implosion.

Ligeti is survived by his wife and a

son, Lukas, a New York-based percussionist.

* * *

Personal recollections:

My first extended contact with Ligeti’s

music came in 1989 with the ‘Clocks

and Clouds’ Festival given on London’s

South Bank by the Philharmonia Orchestra

under the committed baton of Esa-Pekka

Salonen. To say that each concert bemused

me would be an understatement. What

was valuable though was the context

of contrasts Ligeti was set in: Debussy

rang strongly at the time. Each concert

ended with a still sprightly Ligeti

jumping onto the platform with armfuls

of sunflowers, which he then distributed

to the performers… meeting with some

bemused looks in the process! That ‘Clocks

and Clouds’ helped announce some key

works in the Ligeti oeuvre to London

was important in itself. For me, it

sparked an ongoing interest in his music

(not that I always get his point first

on first hearing, but that says far

more about me than Ligeti).

Diary notes made following Pierre-Laurent

Aimard’s 2005 Wigmore Hall recital that

featured a selection of Ligeti’s etudes

record that I found:

Across the Études

many long shadows are cast, not least

by Chopin's and Debussy's compositions

in the genre with the techniques of

Scarlatti and Schumann. Satie, Liszt,

Nancarrow or Hungarian and Balinese

flavours (even the sculptures of Constantin

Brancuşi) infuse and form the

basis of individual studies.

Indeed, it was interesting

for me to note how it took such a refined

pianist as Aimard to show that the Études

could "grow from simplicity to

great complexity, behaving like growing

organisms […] displaying high virtuosity

as a response to my own inadequate piano

technique", as Ligeti himself outlined

they should.

And tradition? “There is only one tradition.

Our music either stands up to it or

not.” His certainly did.

Evan Dickerson

The complete Ligeti discography:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/cgi-perl/music/muze/index.pl?site=music&action=discography&artist_id=830324

Further reading:

György Ligeti by

Richard Toop (Pub: Phaidon

Press, 1999)

Based on interviews with Ligeti, this

book surveys his life and music.

György Ligeti: Music of the

Imagination by Richard

Steinitz (Pub: Northeastern

University Press, 2003)

A scholarly traversal of Ligeti’s compositions.

Image credit © Schott Music

See also

Seen

and Heard Obituary

by Tristan Jakob-Hoff