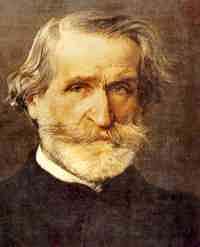

Giuseppe VERDI (1813-1901)

A conspectus of his

life and a review of the audio and video

recordings of his works - Robert Farr

Introduction

Later

in his life, Giuseppe Verdi came to

be called Ďthe glory of Italyí. After

his death, the now unified nation of

Italy mourned as one. Twenty thousand

people lined the streets to pay their

respects as the composerís remains were

carried in a solemn procession through

Milan to their final resting place.

The crowd, aided by the chorus of La

Scala under Toscanini, sang a moving

rendition of Va pensiero, the

chorus of the Hebrew slaves from the

opera Nabucco It was this opera,

composed sixty years before, which set

Verdi on the path to unparalleled national

and international acclaim. He composed

operas for all the major cities of Italy

and for London, Paris, Cairo and St

Petersburg. He played a significant

part in the creation of the nation we

now know as Italy and served in that

countryís first national Parliament.

Later

in his life, Giuseppe Verdi came to

be called Ďthe glory of Italyí. After

his death, the now unified nation of

Italy mourned as one. Twenty thousand

people lined the streets to pay their

respects as the composerís remains were

carried in a solemn procession through

Milan to their final resting place.

The crowd, aided by the chorus of La

Scala under Toscanini, sang a moving

rendition of Va pensiero, the

chorus of the Hebrew slaves from the

opera Nabucco It was this opera,

composed sixty years before, which set

Verdi on the path to unparalleled national

and international acclaim. He composed

operas for all the major cities of Italy

and for London, Paris, Cairo and St

Petersburg. He played a significant

part in the creation of the nation we

now know as Italy and served in that

countryís first national Parliament.

During his later life, and since his

death, Verdiís operas have formed the

backbone of the repertoire of the worldís

opera houses, both great and small.

All his 28 operas are available in well-recorded

studio versions featuring the great

singers of their generation. Many are

also available in video format, increasingly

in varied production styles. Over the

coming months I intend to survey Verdiís

life and the available recordings of

his works. Although some of the lesser

known of Verdiís operas, particularly

those from his earlier earliest compositional

periods, have few recordings his most

popular operas have many. In dealing

with the latter I shall have to make

personal choices as to which I refer

and recommend. Where a recording has

a full review on Musicweb-International.com

a link reference will be provided. Many

of these reviews will be by colleagues

and their opinions may differ from mine.

I will not include references to pirated

live recordings, many in poor sound,

but I will refer to legitimate recordings

of live performances.

The conspectus will appear on

the Musicweb-International.com

classical reviews site at http://www.musicweb-international.com/Current_Reviews.htm

in the following four parts

over the remainder of 2006 under the

title Verdi conspectus.

PART 1. Verdi's background,

getting established and first five

operas from Oberto (1839)

to Ernani (1844)

PART

2. Verdiís Ďanni de galeraí

(galley years). The ten operas

from I due Foscari (1844) to

Luisa Miller (1849)

Forthcoming:

PART

3. Verdiís middle period.

The eight operas from Stiffelio (1850)

to Un ballo in Maschera (1859)

PART

4. Verdiís great final

operas from La Forza del Destino

(1862) to Falstaff (1893) and

including the revisions of Macbeth

and Simon Boccanegra. Also

appendices covering The Requiem, collections

of arias, overtures and choruses.

PART 1. Verdi's

background, getting established and

first five operas from Oberto

(1839) to Ernani (1844)

Giuseppe Verdi was born in October 1813

in La Roncole, a hamlet of one hundred

souls in the plain of the river Po.

Situated in the Duchy of Parma the area

was under the rule of Napoleonic France.

A year after Verdiís birth Russian Cossacks,

allied to Austria, drove out the French

and Parma, like much of what we now

call Italy, came under Austrian control.

The fight for an independent and unified

Italy was later to play an important

part in Verdiís personal and compositional

life.

Verdi drew many short straws in his

long life and these did much to mould

his determined and implacable character.

He carried grudges, was often irascible

and later in life he was prone to exaggerate

earlier personal circumstances and happenings

to give them added colour. He was certainly

not, for example, born into an illiterate

peasant family. His father, Carlo, was

a small landowner and trader and was

literate. Carlo sought education for

his son and by the age of four the young

Giuseppe had begun instruction from

the local priests.  By

the age of eight his aptitude for music

was obvious and his father bought him

a battered spinet. This was rebuilt

free of charge by a local craftsman

impressed by the boyís musical skill

that enabled him to substitute as organist

in the local church. The spinet is now

in the museum of La Scala, Milan.

By

the age of eight his aptitude for music

was obvious and his father bought him

a battered spinet. This was rebuilt

free of charge by a local craftsman

impressed by the boyís musical skill

that enabled him to substitute as organist

in the local church. The spinet is now

in the museum of La Scala, Milan.

In 1823, at age eleven, Verdi entered

the Ďgiannasioí in nearby Busseto, a

town of around two thousand. He lodged

with the local cobbler there for seven

years. During this time he earned money

towards his fees by playing the organ

at Roncole each Sunday and on Feast

days. He claimed to have frequently

walked barefoot the three miles from

Busseto to save his shoe leather. The

young boy was not wholly alone in Busseto.

He came under the eye of Antonio Barezzi,

a wealthy local merchant known to his

father and who was patron of the local

orchestra that met in his house. As

well as formal education at school,

the young Giuseppe began lessons with

Ferdinando Provesi, maestro di cappella

at the local church, and also director

of the local music school and Philharmonic

society. Provesi was also a free thinking

Republican and radical. By the age fifteen

Verdi was conducting the local orchestra

and composing marches as well as arias,

duets, concertos and variations on themes

by famous composers. In all but name

he was Provesiís number two.

Having taught music to Barezziís children

Verdi moved in to lodge with the family

and fell in love with Margherita the

elder daughter, seven months his junior.

Such was his talent that it was hoped

that a scholarship would be granted

for him to study in Milan. This was

eventually forthcoming in 1833. To avoid

the waste of a year Barezzi guaranteed

financial support for the first year

and Verdi applied for admission to the

conservatory for 1832. He was refused

on the grounds that aged eighteen he

was four years beyond the normal age

and not a native of Lombardy-Venetia.

It was a rebuff that Verdi felt very

deeply and never forgot nor forgave.

Barezzi funded private study in Milan

with Lavigna who had been on the staff

at La Scala. Verdi later recalled that

Lavigna concentrated his tuition on

strict counterpoint with nothing but

canons and fugues. Verdi also attended

many performances at La Scala with a

ticket bought by Barezzi.

Verdi completed his studies in 1835.

That year Bellini died and Donizettiís

forty-seventh opera, Lucia di Lammermoor,

was premiered in Naples. Verdi returned

to Busseto. Provesi had died two years

before and Verdi was appointed maestro

di musica but not to succeed his mentor

in the church position. The secular

post involved conducting the concerts

of the Philharmonic society as well

as giving lessons at the music school

in vocal and keyboard music. The contract

was for nine years with a get-out clause

for either party after three. His position

secured, Verdi and Margherita were married

on 4 May 1836. They had two children,

a daughter Virginia Maria born in March

1837 and a son Icilio in July 1838.

Verdiís joy was short-lived as his daughter

died shortly after the birth of his

son.

Whilst Verdi performed his conducting

and teaching duties he composed marches,

overtures and a mass as well as a complete

set of vespers. Regrettably, in later

life Verdi ordered all his early compositions

to be destroyed. Meanwhile he was chaffing

at more ambitious plans including the

composition of an opera. He was in contact

with Milan and a series of letters indicates

the writing of Rocester to a

libretto by a Milanese journalist Antonia

Piazza. He tried to get this staged

in Parma without success. Encouraged

by friends in Milan, and with the help

of the librettist Temistocle Solera,

Verdi revised the work under the title

of Oberto conte di Boniface.

Determined to get the work staged

he resigned his Busseto post in October

1838 and left for Milan with his wife

and surviving child in February 1839.

In 1839, Milan was a city of one hundred

and fifty thousand people. It had been

ceded to Austria under the terms of

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 and was

the capital of the province of Lombardy-Venitia.

The Austrians kept a tight rein on the

local population. There were Austrian

soldiery everywhere and police vigilance

was unceasing as was the detailed activities

of the censor who determined the political

and religious suitability of any play

or opera proposed for presentation in

the cityís theatres. Few of the population

chafed at the situation. Any awareness

of the concept of a united Italy was

restricted to some exiles and literati.

The local aristocracy mingled with artistes

in their salons.

The La Scala theatre was run jointly

with a theatre in Vienna under the direction

of the impresario Bartolomeo Merelli,

who had written libretti for Donizetti.

Its operatic activities could be seen

as a tool of social control; an opiate

administered by a superb roster of singers

and dancers. It was in this milieu that

Verdi sought to establish himself as

an opera composer. He was twenty-six

years of age. By the same age Rossini

had had twenty-four of his operas staged

and was internationally acclaimed.

Merelli agreed to present Verdiís opera

in the spring of 1839 bearing all the

costs of the production himself, a high

risk with a composer untried before

the public. Due to illness among singers,

Oberto conte di Boniface,

No. 1 in the Verdi oeuvre

was not premiered until 17 November

1839. During the rehearsals Verdiís

second child, his son Icilio, died.

The opera was a big enough success for

Merelli to extend the number of scheduled

performances to fourteen that season

and twelve the next. He also sold the

score to Ricordi for the not inconsiderable

sum of two thousand Austrian Lire thus

recouping some of his investment. More

importantly for Verdi, Merelli contracted

the composer for three more operas to

be presented over the next two years

for a fee of four thousand Lire each

and half the money raised if the score

were sold. Oberto is also significant

insofar as it shows the composer drawn

from the start of his career to the

often-troubled father-daughter relationship

that was to occur overtly in so many

of his works.

Oberto missed out in the

seminal initial series of eight early

Verdi operas recorded by Philips between

1971 and 1979 under the stylish baton

of Lamberto Gardelli. Fortunately, Orfeo

took up the challenge with the same

conductor. Their recording of Oberto

features the incomparable Verdi

tenor Carlo Bergonzi and the veteran

Rolando Panerai in a well-sung  performance

(C 105842 H). This recording held the

fort until Philips returned to early

Verdi in 1998 and recorded the work

with Neville Marriner on the rostrum

(454 472-2). The recording features

Samuel Ramey as a sonorous, if not always

ideally steady Oberto, Maria Guleghina

as a generous-toned dramatic Leonora

and the then unknown Lithuanian Violetta

Urmana as a rich voiced Cuniza. Although

the tenor, Stuart Neil, is no match

for Bergonzi he sings with clean tone.

With the added advantages of an ideally

recorded sound and the inclusion as

appendices of music Verdi composed for

the La Scala revival in 1840, this performance

is clearly in first place. The La Scala

additions show something of a significant

step in compositional maturity on Verdiís

part compared

performance

(C 105842 H). This recording held the

fort until Philips returned to early

Verdi in 1998 and recorded the work

with Neville Marriner on the rostrum

(454 472-2). The recording features

Samuel Ramey as a sonorous, if not always

ideally steady Oberto, Maria Guleghina

as a generous-toned dramatic Leonora

and the then unknown Lithuanian Violetta

Urmana as a rich voiced Cuniza. Although

the tenor, Stuart Neil, is no match

for Bergonzi he sings with clean tone.

With the added advantages of an ideally

recorded sound and the inclusion as

appendices of music Verdi composed for

the La Scala revival in 1840, this performance

is clearly in first place. The La Scala

additions show something of a significant

step in compositional maturity on Verdiís

part compared with the original score. What inner

creative force within Verdi, who had

undergone an overwhelmingly difficult

personal and professional period since

the first staging, enabled this step

up in quality of composition can only

be conjectured? (Note:

An Italian correspondent has kindly

brought to my notice a live performance

of Oberto available on both DVD and

CD involving Michele Pertusi, Fabio

Sartori and Dimitra Theodossiu conducted

by Daniele Callegari available on the

Fonè label and which is his preferred

version)

with the original score. What inner

creative force within Verdi, who had

undergone an overwhelmingly difficult

personal and professional period since

the first staging, enabled this step

up in quality of composition can only

be conjectured? (Note:

An Italian correspondent has kindly

brought to my notice a live performance

of Oberto available on both DVD and

CD involving Michele Pertusi, Fabio

Sartori and Dimitra Theodossiu conducted

by Daniele Callegari available on the

Fonè label and which is his preferred

version)

The first of the three contracted operas

to follow Oberto for La Scala

was initially to have been Il proscritto,

a libretto written by Gaetano Rossi

who had provided Rossini with the librettos

for Tancredi and Semiramide.

Before Verdi could commence work Merelliís

plans changed, he needed an opera buffa

and he passed several texts by the house

poet, Romani, over to Verdi. None appealed,

but with time short he settled on ĎIl

finto Stanislauí written twenty

years earlier, performed at La Scala

in 1818 and never revived. The title

of the work was changed to Un

giorno di Regno (A King for

a day), No. 2 in the Verdi oeuvre.

During the workís composition life for

Verdi was difficult. Money was short

and his wife pawned jewels to pay for

their lodgings. Always prone to psychosomatic

symptoms, Verdi suffered from a bad

throat and angina during the composition.

Then, in June 1840 on the feast of Corpus

Christi his beloved wife died of encephalitis.

To crown Verdiís misfortunes Un giorno

di Regno premiered on 5 September

1840 was whistled off the stage at its

first performance. The other five scheduled

performances were cancelled. Whilst

the composer recognised limitations

in his score he was pleased four years

later to note that what had been hissed

at La Scala was a great success in Venice.

In Naples in 1852 it played to full

houses  under

its earlier title. Although Verdi was

not to write another comic opera until

Falstaff in 1893, recent revivals of

Un giorno di Regno, one of which

I caught at the Buxton Festival. It

was thoroughly enjoyable and showed

the quality of the music being quite

worthy of a young composer and equal

to all but the best of Donizettiís comic

operas. The Italian company Cetra thought

the piece sufficiently strong to issue

a recording at the time of the fiftieth

anniversary of the composerís death

in 1951. Although re-issued by Warner-Fonit

it is not a serious competitor against

the 1973 recording in Philipsí early

Verdi series under Gardelliís sympathetic

baton and featuring José Carreras,

Jessye Norman and Fiorenza Cossotto

(422 429 2), which is thoroughly recommendable.

under

its earlier title. Although Verdi was

not to write another comic opera until

Falstaff in 1893, recent revivals of

Un giorno di Regno, one of which

I caught at the Buxton Festival. It

was thoroughly enjoyable and showed

the quality of the music being quite

worthy of a young composer and equal

to all but the best of Donizettiís comic

operas. The Italian company Cetra thought

the piece sufficiently strong to issue

a recording at the time of the fiftieth

anniversary of the composerís death

in 1951. Although re-issued by Warner-Fonit

it is not a serious competitor against

the 1973 recording in Philipsí early

Verdi series under Gardelliís sympathetic

baton and featuring José Carreras,

Jessye Norman and Fiorenza Cossotto

(422 429 2), which is thoroughly recommendable.

With his personal and professional life

in tatters, Verdi returned to Busseto

determined never to compose again. He

later said he spent his time reading

bad novels, surely self-flagellation

for a man who loved Shakespeare and

knew the works of Byron, Schiller and

Victor Hugo intimately. In reality Verdiís

life in this period was not that simple

or desperate. Merelli replaced the scheduled

performances of Un giorno di Regno

with further stagings of Oberto

a mere six weeks after the failed

opening night of the buffo work. As

I have noted, for these performances

Verdi composed entirely new music including

an entrance aria for Cuniza and two

duets. He made more extensive revisions

for performances given in January 1841

during the carnival season in Genoa

and which he had been commissioned to

mount personally. Regrettably none of

the music of these revisions survives.

After returning to Milan from Genoa,

Verdi met Merelli and returned the libretto

of Il proscritto and which the

impresario passed on to Otto Nicolai.

In return Merelli pressed on Verdi the

libretto of Nabucodonosor by

Temistocle Solera and which Nicolai,

then at the height of his Italian career,

had refused. Perhaps to satisfy Merelli,

Verdi read the libretto and was greatly

stimulated by it. Between the spring

and early autumn of 1841 the opera that

came to be called Nabucco,

No. 3 in the Verdi canon

was written. To Verdiís chagrin

its completion was too late for inclusion

in the La Scala season whose sequence

(Cartellone) had already been completed

and published. It took some vehement

correspondence from the composer before

the opera was premiered on 9 March 1842

in secondhand sets but with a first-rate

baritone and bass. Giuseppina Strepponi,

who was to be a great influence in Verdiís

life sang Abigaille, but was in poor

voice. The work was a resounding success

and although the season had only ten

days to run Nabucco was given

eight more times. The delighted Merelli

promptly scheduled a revival for the

following autumn when there were another

sixty-seven performances, breaking all

La Scala records. The chorus Va pensiero

was regularly encored with the Milanese

public, under Austrian occupation, clearly

identifying themselves with the oppressed

Hebrews of the story. It was a tenuous

start to the identification of Verdi

and his operas with the movement later

in the 1840s for the liberation and

unification of Italy called the Risorgimento.

For an opera of such pulsating rhythms,

glorious choruses and well-written parts

for principal soprano, baritone and

bass, Nabucco has curiously few

studio recordings. This may be due to

the impact of the outstanding first

stereo recording by Decca in 1965. It

was recorded in the companyís favourite

venue in Vienna with the orchestra and

chorus of the State Opera under the

baton of Lamberto Gardelli, an incomparable

Verdian who had learned his craft at

the feet of the great Italian opera

conductor, Tulio Serafin. Gardelliís

name will feature regularly in this

conspectus. His conducting of Deccaís

Nabucco, allied to the atmospheric

recording, the singing of the chorus

and the outstanding characterful portrayal

of Tito Gobbi in the name part and Elena

Suliotis as his supposed daughter, made

the recording one of the best of the

period. Suliotis aged 22 was unknown,

but her portrayal of Abigaille brought

big headlines. The role is dramatic

and strenuous. Her entrance recitative

cum aria Pride guerrier ranges

from B below middle C to B in alt and

combines declamatory and coloratura

styles. Suliotis attacks the aria and

the rest of the role with youthful vocal

abandon bordering on the reckless. It

is an approach which presages visceral

and dramatic excitement rather than

vocal beauty, but one which conveys

Abigailleís ruthless character and ultimate

softer plea for forgiveness to great

satisfaction. Gobbi, the odd raw patch

at the top of his voice apart, is as

characterful and vocally expressive

as one would hope. Carlo Cava as the

High Priest could be steadier whilst

the chorus is a match for any of Italyís

best.

EMI ventured into the studio in 1977

with Muti on the rostrum and a strong

trio of principals and a British session

chorus. Renata Scotto, although curdling

the odd high note, sings with typical

character as Abigaille. In the eponymous

role, Tunisian-born Matteo Manuguer ra

sings strongly whist Nicolai Ghiaurov

is the best High Priest on record. The

recording lacks the presence and frisson

of the Decca issue. Against the competition

DGís Berlin recording of 1982 with Sinopoliís

unidiomatic dissection of the score

is a non-starter against the competition.

Many will think that the role of Abigaille

would suit the Callas temperament. In

fact she only ever sang three performances

at age 25 in December 1949 at the Teatro

San Carlo, Naples under Vittorio Gui

and with a raw-toned Gino Bechi as Nabucco.

Recordings in rather poor sound have

appeared from time to time, the latest

(2006) from Membran Music (222387-311).

ra

sings strongly whist Nicolai Ghiaurov

is the best High Priest on record. The

recording lacks the presence and frisson

of the Decca issue. Against the competition

DGís Berlin recording of 1982 with Sinopoliís

unidiomatic dissection of the score

is a non-starter against the competition.

Many will think that the role of Abigaille

would suit the Callas temperament. In

fact she only ever sang three performances

at age 25 in December 1949 at the Teatro

San Carlo, Naples under Vittorio Gui

and with a raw-toned Gino Bechi as Nabucco.

Recordings in rather poor sound have

appeared from time to time, the latest

(2006) from Membran Music (222387-311).

On DVD Nabucco has fared well

with performances, including reviewed

releases listed below (click on the

image to see the review).

| Verona |

1981 |

Renato Bruson (as Nabucco)

Maurizio Arena (conductor) |

|

| La Scala |

1986 |

Renato Bruson

Riccardo Muti |

|

| Naples |

1997 |

Renato Bruson

Paolo Carignani |

|

| the Met |

2001 |

Juan Pons

James Levine |

|

| Piacenza |

2004 |

Ambrogio Maestri |

|

An updated version

with Leo Nucci in the title role appeared

in 2006 (to be reviewed)

In one bound Nabucco put Verdi

to the forefront of Italian opera composers.

The salons of the aristocracy were opened

to the country boy. From this period

his long friendships with the Countesses

Appiani, and particularly Maffei, date.

In their salons he mixed with the cognoscenti

of Milanese literature and music, many

of whom were politically radical thinkers.

After Nabucco Verdi never lacked

for commissions. Indeed there were times

that the pressures from impresarios

and publishers became too great and

his health suffered. In the next nine

years he composed thirteen operas for

all the great theatres of Italy as well

as for London and Paris. Verdi was to

call these years his Ďanni de galeraí

(years in the galleys).

With the raging success of Nabucco

on his hands, La Scala impresario

Merelli wanted to get Verdi started

on his next opera. This would be the

last of the three the composer had contracted

for the theatre after the modest success

of Oberto and including the failure

of Un giorno di Regno. Merelli,

recognising Verdiís newfound status

asked him to name his own fee. Uncertain,

the composer sought the advice of Giuseppina

Strepponi who was singing Abigaille

during the run of Nabucco. She advised

him to ask for the same fee as Bellini

was paid for Norma, eight thousand

Austrian Lire. Verdi asked for, and

got, nine thousand!

Verdiís 4th opera, I

Lombardi alla prima crociata

(the Lombards of the first Crusade)

was premiered at La Scala on 11 February

1843. The libretto was again by Solera

and he and the composer seem intent

on a mark two Nabucco. The theme

has a religious basis and there are

plenty of choral frescoes and more than

a hint of patriotic nationalistic fervour

for the audience to identify with. At

the first performance the act 4 chorus

O Signore, dal tetto natioí (O

Lord, give us a native heath) aroused

a storm of approval just as Va pensiero

had done in Nabucco. The opera

also marked an early brush with the

Church and censor. Verdi refused point-blank

to alter what was written and it required

some diplomacy on Soleraís part with

a sympathetic Chief of Police to settle

on the simple change of Ave Maria

to Salve Maria, which Verdi

accepted. Critical opinion regards the

libretto as poorly constructed and full

of improbabilities in a sequence of

scenes that includes a last act aria

from heaven by the slaughtered tenor

hero. Stagings of an opera with eleven

scenes do not come round often.

Significantly a different roster of

singers were available at La Scala for

I Lombardi than those for Nabucco,

notably the soprano Erminia Frezzolini

who had debuted as Belliniís Beatrice

in 1838 and included Donizettiís

Lucia in her repertoire. Verdi

always wanted to know the singers available

before composing and kept their vocal

characteristics in mind while doing

so. The soprano role in I Lombardi

is utterly different from Abigaille

and reflects Frezzoliniís strengths

being lighter, more flexible and pure-toned.

Without doubt these characteristics

also influenced Verdiís conception of

his heroineís personality and is an

important consideration in the casting

of the role in recordings. There is

no baritone role in the opera but as

well as a principal tenor there is a

tenor comprimario role of greater substance

than that definition usually implies.

The casting of this secondary role on

recordings, along with the principal

tenor, bass and soprano is significant

to enjoyment.

Philips launched their series of eight

recordings of early Verdi operas under

Lamberto Gardelli with I Lombardi.

Recorded in London in 1971 it features

the young Placido Domingo in  pristine

and virile vocal condition as Oronte.

His stylish singing is well matched

by the sonority and evenness of Ruggero

Raimondi as the later contrite villain

Pagano. In the Frezzolini role of Viclinda,

Christina Deutekom is more variable,

often lacking body to her tone. Jerome

Lo Monaco is an excellent second tenor.

This recording held the field until

in 1996 Decca got round to recording

Pavarotti in a role he had first sung

long before in the theatre. It was recorded

in New York under James Levine with

the Met orchestra and chorus. Although

Pavarotti has lost some of the sap from

his tone and lacks the vocal youthfulness

of Domingo, his is a well-sung interpretation.

Samuel Ramey as Pagano whilst showing

some vocal looseness of tone since his

best days is always musical and characterful.

June Anderson scores over Christina

Deutekom for vocal body but lacks some

flexibility. By the time of the recording

James Levine was a much more sympathetic

Verdian than earlier metronomic self.

Where this version scores highly is

in the immediacy of the recording and

the singing of the Metropolitan Opera

Chorus who are full-bodied and vibrant

(Decca 455 287-2). The secondary tenor

role is well taken by Richard Leech

and the importance of the role is highlighted

by the poor performance of Carlo Bini

on the only currently available DVD

version, that of the 1982 La Scala produ

pristine

and virile vocal condition as Oronte.

His stylish singing is well matched

by the sonority and evenness of Ruggero

Raimondi as the later contrite villain

Pagano. In the Frezzolini role of Viclinda,

Christina Deutekom is more variable,

often lacking body to her tone. Jerome

Lo Monaco is an excellent second tenor.

This recording held the field until

in 1996 Decca got round to recording

Pavarotti in a role he had first sung

long before in the theatre. It was recorded

in New York under James Levine with

the Met orchestra and chorus. Although

Pavarotti has lost some of the sap from

his tone and lacks the vocal youthfulness

of Domingo, his is a well-sung interpretation.

Samuel Ramey as Pagano whilst showing

some vocal looseness of tone since his

best days is always musical and characterful.

June Anderson scores over Christina

Deutekom for vocal body but lacks some

flexibility. By the time of the recording

James Levine was a much more sympathetic

Verdian than earlier metronomic self.

Where this version scores highly is

in the immediacy of the recording and

the singing of the Metropolitan Opera

Chorus who are full-bodied and vibrant

(Decca 455 287-2). The secondary tenor

role is well taken by Richard Leech

and the importance of the role is highlighted

by the poor performance of Carlo Bini

on the only currently available DVD

version, that of the 1982 La Scala produ ction.

The vocal strengths in this performance

are provided by José Carreras

as Oronte and Silvano Carroli as Pagano.

As the heroine Ghena Dimitrova is vocally

variable and acts poorly. The production

is traditional with lavishly costumed

Crusaders and Muslims. Brief extracts

are contained on a DVD of scenes from

La Scala stagings from the early 1980s

(see review)

and there is also a recording of the

complete production: La Scala, Milan/Gianandrea

Gavazzeni (see review).

There also exists a live performance

at 'Teatro Ponchielli,' Cremona, Italy.

November 2001 conducted by Tiziano Severini

(see review)

ction.

The vocal strengths in this performance

are provided by José Carreras

as Oronte and Silvano Carroli as Pagano.

As the heroine Ghena Dimitrova is vocally

variable and acts poorly. The production

is traditional with lavishly costumed

Crusaders and Muslims. Brief extracts

are contained on a DVD of scenes from

La Scala stagings from the early 1980s

(see review)

and there is also a recording of the

complete production: La Scala, Milan/Gianandrea

Gavazzeni (see review).

There also exists a live performance

at 'Teatro Ponchielli,' Cremona, Italy.

November 2001 conducted by Tiziano Severini

(see review)

The success of Nabucco and I

Lombardi placed Verdi at the forefront

of Italian opera composers of his generation.

Offers of contracts from around Italy

poured in. Whilst recognising his indebtedness

to impresario Merelliís support, the

composer resisted his blandishments

for another opera for La Scala. Maybe

Verdi was reluctant to push his luck

with another premiere at Italyís leading

House, or perhaps he wished to dip his

toes into other waters. There was also

the matter of his relationship with

the experienced but rather slapdash

librettist Solera. Verdi had a very

acute sense of theatre and felt restricted

by his librettistís rather casual off

the peg approach. Given Soleraís experience,

Verdi did not constantly press for more

apt dramatic situations as he did subsequently

with other librettists.

Meanwhile the Society that owned the

Gran Teatro la Fenice in Venice assembled

to decide on the names of opera composers

for the coming season with Verdi high

on the list. La Fenice was La Scalaís

biggest rival in Northern Italy. Rossini

had won international fame with Tancredi

and LíItaliana in Algeri,

both premiered at the Fenice and concluded

his Italian career in triumph with Semiramide

premiered on 3 February 1823. After

that performance Rossini was escorted

to his lodgings by a flotilla of gondolas,

a water-borne band playing a selection

from his score. A success in Venice

had its own particular flavour and the

prospect was an attraction for Verdi.

Count Alvise di Mocenigo, president

of La Fenice, entered into correspondence

with Verdi, much of which survives.

The composer, aware of his increasing

value drove a hard bargain asking for

twelve thousand Lire for the new opera,

the fee to be paid after the first performance,

not as was usual after the third. After

all if the opera was not well received

there might not be a third. Verdi also

demanded that La Fenice stage I Lombardi

as well as presenting a new opera

to a libretto of the composerís choice.

To write the verses he chose Francesco

Maria Piave who was to be his collaborator

in many subsequent works.

Piaveís name was suggested to Verdi

by the management of La Fenice as a

good versifier. He was almost the same

age as the composer but had never previously

written for the theatre. He and Verdi

were ripe for each other. Although Piaveís

verses were well crafted Verdi constantly

demanded changes, making suggestions

that would give greater dramatic effect.

The librettist was happy with this modus

operandi throughout their long association

that extends through Macbeth and

Rigoletto to the original 1862

version of La forza del destino,

and its 1869 revision, ten operas in

all.

As well as wanting to work with a more

malleable librettist than Solera, Verdi

also wanted to break away from the latterís

grand frescoes and move towards the

setting of more intimate and personal

dramas. After turning down one libretto

from Piave he settled on the subject

of Ernani as his 5th

opera. Based on Victor Hugo, it

featured Verdiís first bandit or outlaw

character. This feeling for the outsider

might reflect something of his introspective

view of himself and his origins. It

is noticeable in later life how he tended

to shelter his own beginnings and the

bruises he sustained along his way to

success.

Although the subject of Ernani had

already been featured in operas by others,

and even considered by Bellini, Verdiís

music brought out the story as no other

had done before. Verdiís Ernani is

written in traditional form with arias,

cabalettas and group scenes with virile

chorus contributions an additional attraction

for composer and audience. Verdi brings

out the character of the conflicting

roles, and their various relationships,

so that each has clear identification

in the music. This manner had, perhaps,

been missing in his earlier successful

duo, which had succeeded on the basis

of the popular appeal their thrusting

melodies and identification with the

frustrations and aspirations of the

audience. Ernani has a density

of musical invention and melody that

is perhaps only matched by Macbeth

before being equalled in Rigoletto,

all with libretti by Piave, and the

great mature period operas that followed.

As with the earlier performances of

I Lombardi in Venice, Ernani

had only a moderate success at its

premiere, the vocal limitations of some

of the soloists being to blame. It had

to wait until felicitous productions

at Vienna in May 1844, and La Scala

in September of that year, for full

recognition of its qualities. For the

La Scala performances additions were

made to the role of Silva with an added

cabaletta in act one to accommodate

the distinguished bass of the time and

promote the role from comprimario to

primo basso. Ernani was the first

of Verdiís operas to be translated into

English and was admired by George Bernard

Shaw. It remained in the Italian repertoire

in Verdiís lifetime, eventually falling

from favour in the early part of the

twentieth century.

In view of the musical invention and

vibrancy of Ernani, including

the melodic arias for all the principals

and some magnificent choruses, the paucity

of recorded versions is surprising.

It perhaps reflects the intellectual

elitism towards early Verdi that was

prevalent among opera house intendants

and some artist and repertoire departments

of recording companies in the heyday

of recorded opera. A 1967 studio recording

made in Rome with Bergonzi as Ernani

and Leontyne Price as Elvira displaced

an early 1950s Cetra issue. It remains

the best-sung version although the recording

has its rough edges (RCA). An atmospheric

1982 Hungaroton recording features a

vibrant Sylvia Sass and a tightly focused

Ernani from Giorgio Lamberti.  This

is now available at mid price (Philips)

but has little to commend it apart from

Gardelliís conducting. A 1982 live La

Scala performance is vibrantly and dramatically

played under Muti and has a starry cast

of Bruson, Ghiaurov, Domingo and Mirella

Freni in the principal roles (EMI on

CD and Warner DVD). Bruson and Domingo

are in superb voice whilst Ghiaurov

sounds suitably authorative as the inflexible

Silva. In the large La Scala theatre,

Freniís voice is a size too small and

she sounds strained at times. Add the

difficult acoustic of La Scala and the

fact that the audio recording is spread

over three CDs and a firm recommendation

in this medium falls on the RCA issue.

The most recent original language audio

recording features the final collaboration

on record of Joan Sutherland and Pavarotti

with support from Nucci and

This

is now available at mid price (Philips)

but has little to commend it apart from

Gardelliís conducting. A 1982 live La

Scala performance is vibrantly and dramatically

played under Muti and has a starry cast

of Bruson, Ghiaurov, Domingo and Mirella

Freni in the principal roles (EMI on

CD and Warner DVD). Bruson and Domingo

are in superb voice whilst Ghiaurov

sounds suitably authorative as the inflexible

Silva. In the large La Scala theatre,

Freniís voice is a size too small and

she sounds strained at times. Add the

difficult acoustic of La Scala and the

fact that the audio recording is spread

over three CDs and a firm recommendation

in this medium falls on the RCA issue.

The most recent original language audio

recording features the final collaboration

on record of Joan Sutherland and Pavarotti

with support from Nucci and  Burchuladze

under Bonynge now at mid price (see

review).

Made in 1987 it sat in Deccaís vaults

for eleven years before seeing the light

of day. The reason is not difficult

to determine as one listens to the tenorís

tentative start, the divaís poor diction

and lack of steadiness in Ernani

involami, Nucciís nasal sound and

the glottal Italian of Burchuladze.

In fairness, Pavarotti improves to give

a worthy and at times thrilling performance.

The latest studio recording is that

on Chandosí Opera In English

series with Alan Opie commendable as

the King (reviewed

in live performance) On DVD the La Scala

performance under Muti is available

from Warner in a resplendent production

by Luca Ronconi. Excerpts from this

issue featuring all the principals can

be seen on a Warner La Scala highlights

DVD (see review).

Burchuladze

under Bonynge now at mid price (see

review).

Made in 1987 it sat in Deccaís vaults

for eleven years before seeing the light

of day. The reason is not difficult

to determine as one listens to the tenorís

tentative start, the divaís poor diction

and lack of steadiness in Ernani

involami, Nucciís nasal sound and

the glottal Italian of Burchuladze.

In fairness, Pavarotti improves to give

a worthy and at times thrilling performance.

The latest studio recording is that

on Chandosí Opera In English

series with Alan Opie commendable as

the King (reviewed

in live performance) On DVD the La Scala

performance under Muti is available

from Warner in a resplendent production

by Luca Ronconi. Excerpts from this

issue featuring all the principals can

be seen on a Warner La Scala highlights

DVD (see review).

On his return to Milan after the Venice

production of Ernani, Verdi found

himself offered contracts to write for

several Italian theatres. He was seen,

aged thirty, as the coming composer

and natural successor to Donizetti.

He was to write ten operas in the remainder

of the decade and to call these years

his ‘anni de galera’ (galley

years). These operas, which were premiered

in Paris and London as well as throughout

Italy, are the subject of Part

2 of this conspectus.

Robert J Farr

Go to: Part

2 Part

3 Part 4