JOYCE HATTO

ATES ORGA

©

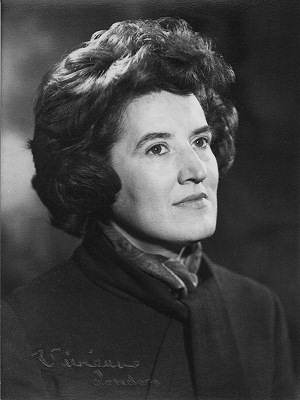

Vivienne of London 1973

©

Vivienne of London 1973

Prelude

Early Days

Serge Krish

Royal Academy of Music

Nikolai Medtner

Alfred Cortot

Vanguard Pianist

Chopin and Liszt

Poland 1956

USSR 1970

Crisis

Scandinavia 1972,

1975

Teaching

Technique

Urgeist versus

Urtext

Reception

Part

2 The

Recordings

see

also

Postscript

to this article 18-10-07

JOYCE

HATTO - A Pianist of Extraordinary

Personality and Promise Comment

and Interview by Burnett James

After

recording 119 CDs, a hidden jewel comes

to light: Fans and critics have

long overlooked pianist Joyce Hatto

By Richard Dyer

Complete list of Joyce

Hatto recordings

available for purchase through MusicWeb

THE ARTIST

‘The musical profession

is a jungle and the

concert platform can

be the loneliest place in the world.

When people flood in

to see you after a concert and tell

you that

"you were marvellous"

that can be very nice, but if they say

"what wonderful

music" then you know that you have

succeeded.’

Joyce Hatto, February

2005

Prelude

I first got to know

the English pianist Joyce Hatto more

than thirty years ago, writing programme

notes for her South Bank and Wigmore

recitals. Quite how I came to be doing

these I can’t remember. But the repertory,

bridging familiar with unknown, was

bold and stimulating, while her playing

struck me as big-hearted and truthful,

adventurous yet with time for finesse.

Music-hunting was her thing, not note-spinning.

She brought to the exercise tone and

quality. And she was generous. In both

the length of her concerts. And the

kindness she showed others lower down

the ladder. One evening came my turn.

In my university days, I’d edited Chopin’s

unpublished Bourrées for

Schott (August 1968, Ed 10984). They’ve

been recorded, played and anthologised

many times since – but it was Joyce

who gave them their premiere, at the

QEH, 11 January 1973, under the auspices

of the Polish Air Force Association.

Minor music maybe, workshop chippings

- but a red-letter occasion even so.

I was grateful.

On leaving Great Portland

Street and the BBC Music Division in

January ’75, I lost touch with Joyce.

I saw some concerts advertised in the

Saturday pages of the Times and

Telegraph, but that was about

it. Twenty-five or so years later, preparing

a Collector’s Guide on Tchaikovsky’s

First Piano Concerto for International

Piano, her name re-surfaced. Not

through her original 1966 Hamburg recording

of the work with Erich Riede but, unexpectedly,

a remake from 1997. Contacting her Royston-based

record company, Concert Artist/Fidelio,

revealed a treasury of recordings from

the early 90s onwards, currently over

a hundred, embracing a wealth of Romantic

masterworks. ‘Probably not since Busoni

has a pianist presented such a wide

and rich in depth repertory,’ believed

the late Burnett James. That broadcasters

and the traditional media have, for

reasons one can only speculate, remained

largely indifferent to this outpouring,

reviewing virtually nothing (or, when

they have, snidely), is one of the mysteries

of modern journalism. How many sixty/seventy-year-old-plus

pianists attempt the integral Haydn,

Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and Prokofiev

sonatas, the complete Brahms, Saint-Saëns

and Rachmaninov concertos, the Chopin

and Schumann catalogue? How many women

do so? English ones at that? A slight,

drawn figure these days maybe (though

still of girlish voice), but the lady’s

alacrity, facility, mental alertness

and imagination is remarkable. An indomitable

force.

1931

Pre-Hammerklavier

1931

Pre-Hammerklavier

Early Days

Born in September 1928,

Joyce grew up in North London, around

the corner from the Medtners. At Mill

Hill School, subsequently renamed Copthall,

two of her tutors instilled a love for

the theatre – Nancy Penhale (who into

her eighties married the literary and

theatre critic Harold Hobson) and Naomi

Lewis. Initially her musical training

was in the hands of sundry teachers,

spirit-shaping encounters, and the émigré

Serge Krish. Subsequently she completed

her piano studies under Zbigniew Drzewiecki

(1890-1971) in Warsaw, and Ilona Kabos

(1892-1973) in London - students respectively

of Paderewski and Árpád

Szendy (one of Liszt’s last pupils).

She sought advice, she’s remarked often,

from Cortot and Henryk Sztompka, Paderewski’s

last student (Chopin), Haskil (Mozart)

and Richter (Prokofiev, the War

Sonatas). She also worked with Nadia

Boulanger. And studied composition with

Seiber and Hindemith – though what pieces

she might have penned remain strictly

private. Hindemith was impressed. ‘An

unusual pianist and not one of the breed

that I am destined to meet […] these

days. I well remember her as a young

student in my composition class […]

because she was the only "composer"

who, when challenged, could sing the

fugue subject that she had chalked on

the board.’

In the summer of 1973

the critic Burnett James got her to

speak graphically about her girlhood:

‘My father played

the piano himself really quite well.

Even before I could read, he would play

to me every evening before I went to

sleep. He was a devotee of Sergei Rachmaninov

and never missed out on any opportunity

to hear him play. A Rachmaninov recital,

or a Queens Hall concert, was always

a memorable occasion. In the morning

I would find the concert programme by

my bed and I liked to stare at Rachmaninov’s

picture. My father would read the programme

notes to me and sometimes play some

of the easier pieces that Rachmaninov

had included in his recital. It was

almost as if Rachmaninov was a relative,

like some sort of uncle! In fact, the

only time I ever saw my father in tears

was the moment we heard the announcement

of the composer’s death on the BBC [end

of March 1943]. I still have some of

those lovely old programmes although,

over the years, I have given many away.

I remember too that my father had great

affection for Mark Hambourg […] I only

heard him play once. He sat at the piano

in a wheelchair and, although disabled,

he gave a magnificent performance of

the Schubert Wanderer Fantasy

and the Chopin Four Ballades

[…] his recordings of some Beethoven

sonatas and the Third Piano Concerto

[November 1929, with Sargent][…] show

him to be a pianist of very considerable

insight and refinement […] My father

was able to teach me himself and I learned

a great deal from him. [But] he was

a very busy man and so I was sent to

a piano teacher. I started my first

lessons when I was about five and made

good progress. Sadly, the teacher, a

Miss Taylor, I remember, died quite

unexpectedly and I was really heart

broken. Soon after I was six I was taken

to play to Marion Holbrooke, the sister

of Joseph Holbrooke, the composer. We

immediately liked each other. She was

a thoroughly nice [down to earth] person,

quite adventurous in her outlook, and

was actually interested in the music.

She also had a high regard for Sergei

Rachmaninov and that, for me, was the

clinching factor […] I was always an

industrious child and, in a very short

time, I was entered for my first grades

examination. I remember that afternoon

very clearly. I was taken to Trinity

College [Mandeville Place] by Miss Holbrooke,

who shepherded me up the staircase to

the large examination room. I had to

play my thoroughly disliked examination

pieces to Sir Granville Bantock. He

was a fatherly figure of a man, although

I remember feeling a little uncertain

about his beard. For some reason I seemed

to amuse him. After I had finished the

set pieces, he thanked me and [contrasting

modern examination protocol] roundly

declared that he had enjoyed my playing.

In my young reasoning, if Sir Granville

liked those pieces, he would be even

more delighted to hear some of my other

repertory. I duly informed him that

I could play better pieces than those

pieces set by the Examination Board.

The great man was even more amused and

he sat back in his chair again saying

that I had better play them then. Needing

no more encouragement I launched into

[…] Kuhlau and Clementi. Sir Granville

clapped loudly and then took my hand

and returned me to Miss Holbrooke who

had been waiting outside. I confess

that, as hard as I tried, I couldn’t

hear what he said to her. Evidently,

everybody was happy. Miss Holbrooke

seemed very pleased […] and took me

out to a special tea at Selfridge’s

Rooftop Garden Restaurant. She told

me that Sir Granville Bantock (she always

used his full name and title) had told

her "this child is a born performer"

and that he had thoroughly enjoyed his

afternoon! That night, I remember thinking

for the first time that perhaps, if

I worked really hard, maybe I could

be playing concertos, like Sergei Rachmaninov,

in the Queens Hall.’ [BJ]

Serge Krish

The Russian-Jewish

conductor and pianist Serge Krish [Krisch]

- virtually forgotten today save for

a single Haydn Wood track from 1946

[An Introduction to The Golden Age

of Light Music, Guild GLCD

5100] and numbers from Tauber’s operetta

Old Chelsea recorded in May 1943

with the BBC Orchestra [BelAge

BLA103.003] but chronicled

by Joyce with evident affection - was

her first ‘mature’ teacher. Krish had

been a pupil of Busoni in Berlin, as

a child attending his legendary Liszt

recitals in the German capital in December

1904. Never fully accorded his worth

or classico-romantic inheritance in

England, he became somewhat debased

by Establishment ‘worthies’ for his

involvement in the British entertainment

scene (he was MD for Tauber in several

Lilac Time revivals, the Serge

Krish Septet was popular, and he conducted

The New Concert Orchestra in ‘a large

number of recordings’ for the Boosey

& Hawkes background music library

[AB]). In people’s minds he was associated

less with ‘highbrow’ culture than the

likes of Black, Chacksfield, Faith,

Farnon, Goodwin, Mantovani, Melachrino,

Rawicz & Landauer, Semprini and

Torch – rarely ever more than BBC Light

Programme personalities (Home Service

at best) whatever their profound professionalism.

Krish instilled in

Joyce a passion for his teacher’s life-long

devotions - Bach, Beethoven and Liszt

– as well as a broader understanding

of the Romantics from Chopin to Brahms

and beyond. She paints an atmospheric

picture of life under him during the

War, in particular his open-ended sessions

at Yarners Coffee House, Upper Regents

Street, a few doors from Broadcasting

House and the shell of the Queen’s Hall,

Langham Place, bombed by the Luftwaffe

in May 1941:

‘I learned a great

deal from him. Not so much in relation

to actual piano technique but more an

understanding of style and sound. I

have a wonderful memory of having coffee

one morning […] Serge quietly nodded

to an elderly gentleman sitting in the

corner poring over a score. "Do

you know who that is," he asked,

I shook my head. "That is the last

pupil of Franz Liszt. It is Frederic

Lamond!" [… he had fascinating

stories about touring w mmkhiyith [or

meeting, or turning pages for] great

artists such as Huberman, Pachmann,

Cortot, Richard Tauber and so many others.

He was a fantastic raconteur and in

those days I was the dry sponge waiting

to soak up all these wonderful stories

[…] My coffee was always cold before

I drank it. Krish, to my young mind,

simply knew everybody and I couldn’t

soak up enough of the tradition I realised

was already vanishing […] at Yarners

[we] would bump in [the] equally legendary

musicians who were still with us. Among

these [early 1943, was] Sir Arnold Bax

accompanied on one occasion by Harriet

Cohen. My teacher would always introduce

me as his "hard working" pupil.’

[JH/BJ] Serge Krish was very much

a "giver" in music. He created

the People’s Palace Symphony Orchestra

for out-of-work orchestral musicians

- taking the name from the then famous

Victorian People’s Palace in East London’s

Mile End Road [Queens’ Building, Queen

Mary University of London]. Not only

did he give players employment and hope,

he also provided opportunities for up

and coming soloists. Clifford Curzon

and Benjamin Britten were among those

who took advantage of gaining experience

and valuable press coverage. The concerts

were given "Royal" approval

by the patronage and attendance of Her

Majesty Queen Mary in full regalia in

1935. Krish was unable to follow a solo

career as he’d injured a hand as a soldier

in the 1914-18 War. But he made a considerable

reputation accompanying and partnering

star artists. For a few years he was

resident in America, befriending Leopold

Godowsky. It was through Serge Krish

that I became friendly with Benno Moiseiwitsch

and I was made very welcome in that

family and the whole group of quite

exceptional musicians who surrounded

it. [In 1942] Moiseiwitsch’s daughter,

Tanya, married Serge’s youngest son,

Felix – who died in action eleven weeks

later [his RAF Lancaster crashing over

Lincolnshire farmland, 12 February 1943:

within days Serge was back in the recording

studio, conducting for Tauber]. She

never re-married.’ [AO]

©

Angus McBean 1958

©

Angus McBean 1958

Royal Academy of Music

Pianistically the great-grand-daughter

of Liszt and grand-daughter of Busoni

and Paderewski, poetically the niece

of Rachmaninov, Joyce as a child contemplated

attending the Royal Academy of Music.

In the end it was not to be. She went

to none of the London music colleges,

content to do without the peers, accolades

or prejudices that come from such association.

‘When I was twelve

years of age [1940/41] I wrote to Sir

Stanley Marchant, then Principal of

the Royal Academy of Music, to ask about

the opportunities of studying music

there. He sent me a charming letter

suggesting I should meet Michael Head

at the Academy and play for him. I duly

made an appointment, bringing along

a Mozart sonata and a small group of

Chopin Préludes. He was

pleased and took me on a tour of the

building, pointing to various walls

bearing Rolls of Honour on which his

name for winning various prizes as a

student was frequently displayed. Michael

Head said that he would be happy to

take me himself or give me a letter

of introduction to any other Academy

professor. But he then rather spoilt

the occasion by telling me that the

musical profession was a very hard and

precarious life even for very successful

people and it might be better just to

play for pleasure. This negative attitude

didn’t appeal to the twelve year old

before him. Combined with the rather

dreary atmosphere of a rather dreary

building made me decide that it wasn’t

for me. In spite of this we rather liked

each other and we kept in touch. A few

years later I found myself in Leek,

Staffordshire, giving a piano recital

in a series where Michael Head had been

booked to do one of his charming one-man

shows in which he used to play and sing

his own compositions. The following

year we featured together in three other

concert series. He sent me a little

card on each occasion - "I think

you have made your point," he wrote.

He was a nice man and I often listened

to his broadcasts. Sometime later Mr

Krish arranged for me to have harmony

and theory lessons with Professor Leslie

Reegan at the Academy. My lessons frequently

followed on, as it happened, after Peter

Katin. I really didn’t like the atmosphere,

an elderly upright piano, piled high

with dirty tea cups, fourteen of them,

and frequent interruptions. Then one

day he turned to me and said "It’s

really more important for a young girl

like you to be able to cook a good roast

dinner and not bother with all this!"

I left him and the Academy for good

soon after, to study with Mátyás

Seiber.’

Nikolai Medtner

‘Medtner and his

wife and grey tabby lived in a house

on the crossing of Ravenscroft Avenue

and Wentworth Road, NW11. Joyce played

several of his works to him including

(on the advice of Krish) four sonatas

and at one time the Third Concerto

which he’d premiered with Boult towards

the end of the War [Royal Albert Hall,

19 February 1944]. Some of his stuff

is worthwhile but you need to be an

exceptionally good musician to dig out

his message. I think Medtner suffered

as pianists didn't really find it easy

to tap into anything. I think, too,

he was emotionally unsuited to performance.

I heard him in a recital just once:

to my young ears it sounded all so uncommitted.

Moiseiwitsch played a handful of his

pieces and could make them sound something

with his lovely tone. But he didn't

play much because Medtner never expressed

a "Thanks Benno" and wanted

to spend hours giving him advice on

how to play everything. Benno got fed

up with that very soon. He only took

up his music anyway because Rachmaninov

had asked him if he could help Medtner.

Eileen Joyce was going to play a group

of Medtner pieces after she heard Joyce

play the Danza Festiva. Medtner

immediately wanted to change her technique

and instruct her on every note. She

also got fed up with that and gave him

a big miss. Everybody in the end most

people got fed up with Medtner because

he was such a worrier. According to

Benno, he plagued the life out of Rachmaninov

to help him with concerts in America

and with publishers. Mrs Medtner was

charming and bore all this with great

fortitude. Krish had a sister who lived

a few houses away from the Medtners.’

[WB-C]

Alfred Cortot

‘Alfred Cortot was,

I think, a very honest teacher and musician.

He was certainly the most musical musician

that I ever met. His voice was musical,

mesmeric in French but still hypnotic

in English. He poured out comments and

information on every aspect of music

and art. His astonishing grasp of the

wonderland of Schumann’s musical world

has been partially eclipsed by his reputation

as a Chopin player. His playing of Ravel

was simply in another sphere. I shall

never forget his comments on Beethoven’s

Op 109 or Liszt’s Dante Sonata

and the two Legends. A performance

to him was the stuff of life and breathe

itself. Music was not to be reduced

to an ego trip for those pianists who

feel that they are rendering composers,

however eminent, a great service by

simply playing their music at all. Quite

contrary to some of the comments that

I have read over the years from Cortot

"pupils" I never found him

particularly dogmatic, egocentric or

egoistic. […] Alfred Cortot was first

and last a musician. To him being a

musician meant making music, communicating

music, and bringing the composer and

his music to life. He continually underlined

the importance of reading and learning

as much as possible about the lives

and times of the composers.’ [JH/Chopin]

Vanguard Pianist

During the late forties

and fifties Joyce lists appearances

with conductors ranging from de Sabata

and Beecham to Kletzki and Martinon.

She worked with Britten, Vaughan Williams

(whose Piano Concerto she wanted to

programme), and Malcolm Arnold (of the

‘immaculate suit’).

One day at the old Sadler’s Wells

Theatre, around 1946/47, Constant Lambert

encouraged her to take on Bax’s Symphonic

Variations: ‘You’ll have the field to

yourself – nobody will touch it [no

one did till the late eighties]. You

might not like it though, it lasts fifty

minutes and the pianist never gets the

big tune’. Standing by British music,

playing it in Britain and overseas,

she did her share promoting not only

Bax, Bliss, Bowen, Ireland and Rawsthorne

but also some of the rarer, obscurer

byways of the repertory - from Lambert’s

‘chamber’ Concerto for piano and nine

players to Walter Thomas Cooper’s Third

for piano and strings, premiered under

Martin Fogell at the Wigmore Hall in

1954. A ‘technique […] beyond prestidigitation,’

affirmed Hindemith. ‘Her performance

of my Ludus tonalis […], so beautiful

in some of the quieter moments, [moved

me] to tears. There were no technical

problems for her, and her understanding

of my intentions – even when not ideally

realised in my notation – showed that

she was [firstly a] musician not [a]

technician. Her wonderful independence

of line would have surely seduced Johann

Sebastian into composing another Forty

Eight just for her.’

Chopin and Liszt

From the beginning

Chopin and Liszt featured high in Joyce’s

sympathies, at a time in England when

neither composer necessarily guaranteed

serious aspiration on the part of the

artist. In the ’50s, whatever the intent

and demonstration of Rubinstein and

Malcuzynski, Horowitz and Gilels, Lipatti

and Michelangeli, Chopin was pretty

tunes, encores, and box-office guarantee,

Liszt was show-music, tinsel and Liberace.

Promoters’ fare rather than critical

fodder. (In his book Reflections

on Liszt, Alan Walker concludes

the great man is even now [2005]

denied his ‘proper place in history’,

even as we approach the bicentenary

of his birth.) Inspired by Arthur Hedley

writing on Chopin (1947), ‘fired up’

by Sacheverell Sitwell’s enthusiasm

for Liszt (1934), Joyce had other ideas.

‘Sacheverell’s enlightened

rapport for Liszt’s music induced me

to explore as much of his music as I

could find in wartime London’s second

hand book and music shops. One of my

favourite haunts was Harridge, a wonderful

Mecca of second-hand and rare records

in Soho’s Lisle Street. Among the records

that I bought there was the [Abbey Road

1932] Horowitz recording of the Liszt

Sonata and the pre-war recordings

made by [another Blumenfeld student]

Simon Barere. I also acquired a number

of equally compelling performances of

then unusual repertoire by Louis Kentner

[Ilona Kabos’s husband]. He nearly always

[included] interesting Liszt works in

his recital programmes.’ [BJ]

Spurning routine programming,

Joyce presented inventive juxtapositions

and originally themed series. One such,

in 1953, at the age of twenty-five,

offered the integral nocturnes of Chopin

and Field with programme notes by Chislett

(Field) and Hedley (Chopin). Another,

further into the decade, featured all

the Beethoven symphonies transcribed

by Liszt at Cowdray Hall, a popular

Central London venue of the period benefiting

from ‘a nice acoustic’ [WB-C]. Publicised

through a blurb by the composer and

former BBC Third Programme producer

Humphrey Searle, the cycle was presented

across four concerts – Nos 1-3, 4-6,

7-8, 9 – the third including additionally

Alkan’s transcription plus cadenza of

the first movement of the C minor Concerto.

(Nos 5-6 plus the Alkan were to be repeated

in an unfinished series at the Wigmore

twenty years later, among Joyce’s last

stage appearances.) Remarkably, by modern

reception values, the project – the

first known modern performance of the

cycle, nearly thirty years before Idil

Biret’s Montpelier Festival claim -

attracted no critical attention. The

Liszt Society (whose Committee then

included Kentner, Sitwell and Walton)

‘promoted’ the series - but ‘gave no

funding towards it’ [WB-C].

Of the Chopin-Field

venture, Hedley recalled in 1958:

‘Joyce Hatto […]

is still a young pianist [but] with

a particular, and proven, feeling for

Chopin. She is unusual, rather unique

among English pianists, in understanding

the darker side of the composer. She

does not strive for pretty effects and

her projection of Chopin as a ‘big’

composer sets her aside from most of

her contemporaries. Her often quite

astonishingly ample technique always

allows her additional scope in conveying

her interpretive views. It is a considerable

achievement of will that she never allows

her own forceful personality to intrude

on that of the composer. In her performance

of the Field Nocturnes [King’s

Lynn; Friends Meeting House, King’s

Cross Road, London; Bath Pump Room]

she never made the mistake of "anticipating"

what was known to be on the horizon

in Chopin. She allowed Field his moment

in time - no mean feat and a revelatory

one.’ [AH]

The notion of Chopin

as a ‘big’ composer was one shared with,

if not inherited from, Cortot:

‘His remarks on

all the Chopin that I ever played to

him were directed to the feeling and

content of each piece and how essential

it was in all Chopin performances to

rid oneself of the sticky sentimentality

that was so often presented as being

"authentic". Time and time

again he emphasized to me "Chopin

is a big composer and the sentiment

expressed in his music is masculine

–not effeminate".’ [JH/Chopin]

When, from what used

to be the Friends of Chopin, Lucie Swiatek

founded the London Chopin Society in

1971 under the presidency of Maurice

Jacobson, Joyce was appointed to the

first committee – joining Daisy Kennedy

and the former Minister of State, Welsh

Office, Baroness Eirene White.

Poland 1956

You will not find any

evaluation of Joyce as a Chopin specialist

in James Methuen-Campbell’s Chopin

Playing (London: 1981) – saying

more about the author than the artist.

Her dedication to the composer is complete.

From early concert days to late recordings

and occasional CD annotations. From

visits to Poland (the first, part of

an official British delegation, coinciding

with the anti-communist Poznań

uprising of June 1956) to associations

with that country’s musicians, conductors

and orchestras - her preferred recording

partners. The Polish trips showed

her the people, the earth and high art,

the history of a land under occupation.

She played anything anywhere for anyone.

In Warsaw she took part in a recital

series including Zak, Rubinstein and

Malcuzynski. She visited the tracks

and sheds of Auschwitz, eleven years

on from its past.

‘An experience that

really changed me. One can hardly believe

the horrors of that place. I was able

to speak to people who had been in the

camp. A man who had worked on the ovens.

A woman violinist, who had played in

the orchestra to welcome new arrivals.

I was not aware that quite a number

of British people, including our prisoners

of war, had perished there. However

much one has read, however many pictures

one has seen, you can never be prepared

to actually see and walk around the

buildings for yourself. The atmosphere

was so heavy and there were few birds

to sing a requiem […] Heart-rending

stacks of suitcases, clothing and shoes.

Spectacles, personal belongings of every

possible description piled high. These

filled room, after room, after room.

I noticed stacks of music. A volume

of Brahms’s piano music, with the name

of the owner so carefully written on

the cover, was clearly visible […] It

was the same Breitkopf Edition that

I had at home. Possibly I had been practising

the same Brahms pieces as this unknown

Polish pianist who had endured such

a terrible fate. It has had a lasting

effect on my life […] I will always

remember it.’ [BJ]

USSR 1970

In May 1970 Joyce’s

Guildford Philharmonic performance of

Bax’s Symphonic Variations and the ensuing

EMI Abbey Road sessions were attended

by the Soviet Cultural Attaché

in London. On the basis of what he heard,

he confirmed he would recommend the

piece for inclusion on her forthcoming

tour of the Soviet Union (ipso

facto entrusting to her its Soviet

premiere).

‘The works that

I had been booked to play were Mozart’s

A major Concerto K 488, Brahms

D minor, Beethoven’s Third

(Alkan cadenza), Chopin’s F minor

and, finally, the Bax Variations.

I also took a Liszt recital and a special

[…] programme for some engagements in

universities and [conservatoires]. This

contained the Bach Goldberg Variations

and Rachmaninov’s First Piano Sonata.

In the Liszt recital, in place of the

B minor Sonata, I included the

rarely played Grand Concert Solo.

The B minor Sonata seemed particularly

popular with young Russian pianists

and featured in three of the five recitals

I was invited to attend. The Bax […]

really stunned and surprised everybody

[…] a great success.’ [BJ]

The public warmed to

her Brahms D minor, one reviewer commenting:

‘Her performance […]

was a triumph. The technical virtuosity

was compelling […] but it was the blazing

passion that brought the huge audience

to its feet. To repeat the third movement

as an encore was more than a gesture

[…] It was a challenge thrown down to

the orchestra who responded magnificently.

Joyce Hatto [is] an exceptionally fine

pianist with no fear of heights. Her

playing in the Brahms concerto was a

benchmark by which all future pianists

can be judged. [She] has a charming

grace of manner and her complete humility

to the demands of the composer sets

her aside as being special.’

Crisis

But for the fighter

in Joyce, Bax might have been her swansong.

She was 41 - and ill with cancer. She

has been ever since.

‘She went straight

from the EMI Studios to hospital for

surgery the next day. It was then found

that with a blood count just on 50 [normal

MCV being 86-98 femtoliters] any operation

was impossible. The surgeon was adamant

that she would never recover. Immediate

blood transfusions were given and a

week to regain strength. Her doctors,

one of whom was in attendance at the

Guildford concert and the London recording,

said that she was "not in a fit

state to do either". Well, she

did recover, toured Russia and Scandinavia,

and played a number of Liszt recitals.

She only finally gave up on the public

stage when a critic mocked her appearance.

Her name nonetheless remained in the

record catalogues. In 1980-90 there

were 70 cassette titles available, distributed

in Britain, the USA, South Africa, Australia,

Japan and the Eastern Bloc. When the

UK national broadsheets stopped reviewing

cassettes, it gave a rather false impression

of the business, denying Joyce her presence

as a recording artist.’ [WB-C]

‘She doesn't want to play in public

[again] because she never knows when

the pain will start, or when it will

stop, and she refuses to take drugs.

Nothing has stopped her, and I believe

the illness has added a third dimension

to her playing; she gets at what is

inside the music, what lies behind it.’

[WB-C, quoted by RD]

Scandinavia

1972, 1975

The warmth of Joyce’s

reception abroad has given her good

memories. In 1972, for the first time

in ten years, she returned to Sweden

to play Rachmaninov’s Third Concerto,

the Schumann, and an all-Schubert programme.

The Göteborgs-Posten atmospherically

caught the occasion – ‘Joyce Hatto the

astonishing English pianist’:

‘Her performance

of the Rachmaninov Third Piano Concerto

(which she played on her début

here in 1962) has not dimmed but become

even more impassioned. The alternative

"big" cadenza in the first

movement would seem an almost impossible

demand for a diminutive woman pianist.

But here, as in the thrilling finale,

[she] completely dominated her Steinway

and it was noticeable that it was the

orchestral players who were sweating,

not the soloist! The explosive reception

she received demanded six encores. These

ranged from an incredible Mephisto

Waltz to equally fine performances

of Rachmaninov’s Preludes in C minor

and G minor, ending finally with

three Scarlatti sonatas, no doubt beautifully

chosen to calm an emotionally charged

audience.’

Of her ‘brave’ Schubert

offering, they wrote:

‘Miss Hatto’s sponsors

need not have worried at this choice

of programme as the hall was more than

comfortably filled. This English pianist,

still young by international standards,

has a phenomenal technique. It is phenomenal

not simply in terms of power and the

speed of her dazzling finger work (yes

she does have all that) but in the vast

variety of different sounds she is able

to coax from her instrument. Phenomenal

too is the complete independence of

her hands. This alone enables her to

colour her playing in a way few pianists

can achieve […] all this seemingly additional

pianistic technique is placed at the

disposal of the composer. Conventional

criticisms of Schubert’s piano writing

no longer concern us and we are free

to gasp at the wonderful sound pictures

the composer, through the hands of his

interpreter, paints for us. Nowhere

was this more convincingly illustrated

than in the Wanderer Fantasy,

receiving an astonishing performance

of power and pianistic conviction.’

A pair of Schubert

sonatas in Stockholm galvanised the

critic of Svenska Dagbladet:

‘Joyce Hatto [is]

a thoughtful pianist of quite exceptional

power and an astonishing, seemingly

endless, variety of keyboard colour.

The clarity of her vision in all she

plays and the profundity of thought

that permeates her music-making set

her uniquely aside. Her individual conception

of Schubert’s Sonata in B flat major

was completely at odds with the interpretations

we hear in concert and on recordings

by an array of the world’s greatest

pianists. An expected mood of boundless

despair was replaced by a searching

performance that found hope and looked

forward to the future with more than

a glint of confidence […] In this deeply

considered performance we were held

completely in awe of the music and were

made to feel that Schubert has not given

up his struggle but is still reaching

out for fulfilment and some happiness.

Rare indeed are the pianists that can

grip, mould and hold an audience for

forty-five minutes without a single

cough to break the spell. [Miss Hatto

opened her recital] with a daringly

different view of Schubert’s "sunny"

little Sonata in A Major D 664.

In the opening Allegro moderato

(played with exposition repeat) she

made us deeply aware of the underlying

sadness that is never far away in Schubert,

and our eyes were opened to the real

stature of this piece. The final movement

was a magical journey in which the composer’s

rapid changes of mood were further illuminated

by this artist’s ability to coax so

many different sounds from her instrument.’

Teaching

‘It is really only

possible to teach well by example. If

you can’t illustrate a difficult passage

fluently yourself how can a pupil accept

advice on technique?’ [JH/Chopin]

Joyce has spent a large

part of her life teaching. Not in a

time-restricted, prescriptive college

environment but privately. On a one-to-one,

hands-on basis, the problems and strengths

of each student individually, inspirationally

addressed, helped and remedied.

‘I have always enjoyed

teaching. It is true that many musicians

do not. I have always loved the piano.

For me there is a frisson merely to

see the sight of the piano open and

standing alone on the concert platform.

Waiting for the pianist to appear, sit

down, and launch into the adventure

of a performance […] I think that most

people are born with a talent for something.

The people who are happiest in life

are those who have been able to discover,

or recognise, their own particular god-given

gift, and go all out for it! There is

that well worn and very unfair adage

that "People who can’t perform

teach". I love the piano whether

I am playing myself or teaching young

pianists how to play well or […] better.

Good teaching, [in whatever discipline]

whether it is mathematics, physics,

languages, ballet, or opera, must be

recognised as vital to the success of

our society. Inspired teaching always

produces results and who better to inspire

a young performer than advice given

freely by somebody who has been through

the mill.’ [BJ]

In the essay accompanying

her 75th anniversary edition

of the Chopin Studies she tellingly

quotes a conversation Cortot had with

her:

‘What one must always

try to do in teaching is to convince

the student that they have something

to say (if they have) and give them

confidence to expand on that. If they

can say nothing when faced with a great

work of art or find nothing meaningful

of themselves to weave into their playing,

then I advise them to take up cartography,

geography, swimming or anything else

where they can do no harm. I never ever

advise them to take up teaching as an

alternative to public performance. What

can they teach for God’s sake!’

[JH/Chopin]

Seeking out Joyce’s

students has never been easy. (Gail

Buckingham made a brief name for herself

in the late-60s, sailing the Niobe

Fantasy among other things, but then

vanished.) Possibly because many, like

Chopin’s, were not destined for a life

in music. One such grateful soul, circa

1955, was the novelist Rose Tremain,

whose spent her boarding-school days

at Crofton Grange in Hertfordshire –

and still keeps in touch:

‘Crofton Grange

was hard at first. I was homesick. [But]

life got easier and then I began to

like it. There was a lot of time to

fill up and we filled it up stupendously

well, with art and drama and music […]

I longed to be a good pianist, because

we had the concert pianist, Joyce Hatto,

to teach us and the sound she made on

the wonky old Crofton grand was unique

in the history of the school. I never

got beyond Grade 3, despite her brilliant

instruction. My fingers wouldn’t do

the fast bits, so I had to play very

slow sonatas.’ (The Scotsman,

10 December 2003)

Technique

Among Joyce’s favourite

maxims is Arthur Rubinstein’s ‘there

is no method – there is only the right

way’. Over lunch in Cambridge, at the

University Arms, Valentine’s Day 2005,

discussing facets of piano technique,

she enumerated some of her basic principles

and understandings.

‘(1) The mind plays

the piano.

(2) The mind tells

the fingers what to do before they do

it.

(3) The mind instructs

the whole arm to be totally relaxed

all the time.

(4) Everything travels

through the whole arm dictated by the

mind. One doesn’t have to be concerned

with ‘arm weight’, ‘wrist tension’ or

such things. It is all completely irrelevant

and will simply get in the way.

(5) Pianists move quicker

than they play. The articulation is

dictated by the mind and the fingers

are always close to the keys. Krystian

Zimerman and Evgeny Kissin demonstrate

this.

In this way of playing

all sound is released out of the instrument,

and the mind chooses its repertory of

sounds.

(6) The pianist sits

low and away from the keyboard so that

the elbow is lower than the keyboard.

(7) The hand is

not ‘prepared’ in anyway but remains

outstretched. The thumb is always away

from the fingers, which can then be

articulate. There is no such thing as

a weak finger.

[‘It is the tendons that are

strengthened not the "fingers"

as such. The tip of the finger to the

first knuckle doesn't cave in’ (WB-C)]

(8) If applied successfully

and the hand is lifted off, by the other

arm, it will be as light as a feather

[a simple demonstration proves the

point – as well as showing remarkable

tendon development.

(9) The sound is caught

by the cushion pads on each finger as

the weight travels down the arm.

(10) Legato is transferring

the weight from one finger to another.

This needs slow practise at first to

connect the relaxation from one finger

to another. The thumb is used as another

finger and this achieves a pure legato.

(11) The lazier

[more relaxed] the arm the bigger

the tone coming through the instrument.’

[AO]

Arrau once told me

he never bothered with drill practice:

the works he played gave him the material

he needed to keep in shape. Joyce goes

along with that to an extent. But the

regular playing of technical/musical

studies is still an important routine.

As a child living through the Blitz

near a munitions factory, she honed

her fingers on Cortot’s 1928 Rational

Principles of Piano Technique. Did

an hour of Bach. Immersed herself in

Liszt. And wandered the highways of

Chopin-Godowsky, courtesy of Krish.

She still lives with Clementi’s Gradus

ad Parnassum. ‘When discussing the

Paganini Études with Joyce

Hatto at a Liszt Society recital,’ Humphrey

Searle noted in 1952, ‘I was interested,

but not entirely surprised, to learn

from her that she regularly uses a number

of the [late] Liszt Technical Studies,

combined with Clementi’s Gradus ad

Parnassum, as a basis to build and

maintain her very formidable technical

prowess.’ [HS]

Urgeist versus

Urtext

Joyce is more interested

in Urgeist than Urtext.

Spirit before letter. Composer before

editor.

‘I always mistrust

Urtext editions as they are never

exactly what they proclaim. Mozart and

Chopin always seem to attract ‘scholarship’

of a kind that can never accept that

they might actually have meant what

they put down on paper. Any deviation

from notation in a first movement repeat

or in a reprise is immediately put down

to a composer having simply been tired,

forgetful, ignorant or perverse. Over

the years Chopin has suffered badly

from editors who think that their understanding

of harmony is to be more trusted. They

water down piquant harmonies or discords

to fit in with their own lesser flights

of fancy. This has happened in some

Chopin Urtext Editions when even

the composer's own corrections of the

original plate-makers’ engravings have

gone "uncorrected". Existing

copies of first editions used by the

composer's pupils and assiduously corrected

by him, pointing to occasionally quite

different conclusions [alternatives],

are also often ignored, despite their

accessibility [see Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger,

Chopin: Pianist and Teacher,

Cambridge: 1986].’ [AO]

From a generation in

a country, England, that came late to

the Germanic Urtext mentality

– well-thumbed 19th century

derived or influenced editions of the

classics still outnumber Henle/Bärenreiter/Wiener

Urtext ‘purifications’ in the

main British music colleges – Joyce

has no ethical problem using the 1906

Augener text of Mozart’s sonatas edited

by Franklin Taylor, one of Clara Schumann’s

pupils. But only as a basic notation

reference, open to academic scrutiny.

Occasionally, she says, she’ll make

‘changes in those instances where Mozart

is known to have changed his mind or

had second thoughts’. In the slow movement

of the F major Sonata K 332, for example,

she opts to play the ornamented second

half variant of the first edition (1784)

on the grounds that (a) ‘though its

authenticity [cannot] be proved, it

seems not impossible that Mozart is

[the] author’ (Salzburg Mozarteum-Ausgabe,

Vienna: 1950); and (b) it ‘rings true’

(Frederick Neumann, Ornamentation

and Improvisation in Mozart, Princeton:

1986). She points out, with respect

to dynamics, that she will accord or

not with an editor’s opinion subject

to her own perception of a passage or

context. ‘Mozart himself employed very

few expression marks, for the most part

f and p.

These signs were to indicate the general

character of a phrase, and not to imply

a monotonous continuance

of the same degree of force or sound.’

In the case of Mussorgsky’s

Pictures at an Exhibition, getting

to the Urgeist of the music was

through Paul Lamm’s edition (Moscow:

1931, basis of the International Music

Company text, New York: 1952 – explaining,

for instance, the fortissimo

at the start of Bydlo, and the

original C-D flat-B flat ending of ‘Samuel’

Goldenberg und ‘Schmuÿle’.

The autograph (facsimile, Moscow:1975/82).

And first-hand contact with London’s

‘White Russian’ Romantics – the Krish

circle.

‘When I first played

Pictures to Moiseiwitsch he told

me quite casually that Rachmaninov had

considered producing a "performing

edition" but had given up on the

task feeling that it was better to leave

well alone. Rachmaninov, however, did

pass on some of his ideas to Medtner

who allowed me to copy them into my

own copy of the music. I am not aware

that Rachmaninov actually performed

the piece, but I do know that he intended

to play it in a Boston recital before

abandoning the possibility. In my recording

[CACD 9129-2] I incorporate one

or two of the thoughts he communicated

to Medtner. I do not entertain any harmonic

changes. But I do divide up some chords

for the sake of harmonic emphasis. I

endeavour to play each of the Promenades

slightly differently so as to make for

a more thoughtful (or thought about)

performance. I have no specific "authority"

for this – though Cortot (who suggested

I should play the piece originally)

did pass on some splendid personal comments

and advice. The difficulty in playing

Pictures is to make a diffuse

piece, albeit a very great one, that

little bit more cohesive, without

sprawling about in one’s own unbridled

emotions.’ [AO]

Reception

Finding out anything

about Joyce, anything corroborative,

is a challenge. Her lack of vanity,

self-effacement, and desire to be behind

the composer, the music, the CD, to

be the medium rather than the personality,

has over the years created an effective

information block. Odd programmes and

advertisements surface from time to

time. And there’s the standard management

biography. But otherwise one hunts vainly

for information. No dictionary or handbook

entries. Virtually no third-party references.

Few readily accessible reviews from

her concert days (she’s never kept press

cuttings). Her Concert Artist CDs however,

offering an in-depth picture of her

(present day) strengths and breadth,

have helped redress the balance somewhat,

attracting notice in Europe and America.

The first major piece about her appeared

on the internet: the 1973 Burnett James

interview. An intriguing read – too

intriguing to have been withheld for

thirty years. A German profile then

featured in Fono Forum, an admiring

Frank Siebert concluding that ‘the piano

art of Joyce Hatto stands in contrast

to today's ostentatious music business’.

Subsequently Richard Dyer took up the

story, calling her ‘a hidden jewel’.

‘Joyce Hatto must be the greatest living

pianist that almost no one has ever

heard of […] The best of [her CDs] document

the art of a major musician’ (Boston

Globe, 21 August 2005).

Part 2

The Recordings