Allegro – a

new era in music recording

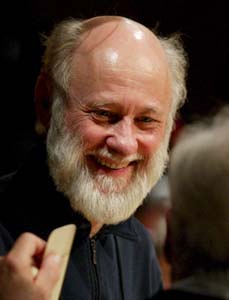

Christopher Nupen talks to Anne Ozorio

about

the release of a series of Allegro Films on DVD

“Christopher Nupen pioneered a style of filming music and

music-making for television in which his excellence has

rarely been equalled and never excelled …. His films

will endure forever as reference documents to the executant’s

art in the 20th century and as constant sources

of musical delight” – Jeremy Isaacs

(Chief Executive, Channel Four and later General Director,

Royal Opera House)

Only a hundred years ago, there

was no way musical performance could

be preserved. The art of recording

is really so new that we haven’t,

perhaps, even begun to explore the

possibilities. Recordings alone don’t

capture the experience of live performance.

Filmed music is in itself a new art

form, which can expand a deeper appreciation

of what is heard.

Only a hundred years ago, there

was no way musical performance could

be preserved. The art of recording

is really so new that we haven’t,

perhaps, even begun to explore the

possibilities. Recordings alone don’t

capture the experience of live performance.

Filmed music is in itself a new art

form, which can expand a deeper appreciation

of what is heard.

Allegro Films is launching a series

of DVDs, to be distributed by Naxos.

These will be reference recordings,

for they preserve not only performance,

but the spirit of the artists, and

the context of the music.

Christopher Nupen pioneered the concept

of filming music. His film The

Trout, a performance of Schubert’s

great Quintet was something of a revolution.

It featured Jacqueline du Pré, Daniel

Barenboim, Pinchas Zuckerman, Itzhak

Perlman and Zubin Mehta, playing in

recital, but was filmed so sensitively

that it captured the spirit of the

artists as well as their performance.

Despite originally receiving a bad

review in the Times and being criticised

by the BBC , both for its form and

its title, it went on to become the

most frequently broadcast classical

music film ever made. .(see review)

In 2005, Jacqueline du Pre in Portrait

became the biggest selling classical

DVD of the year. .

Film adds a powerful dimension to

the music experience. As Nupen says,

film has been around long enough that

people are used to understanding its

“grammar”. People are used to the

way the medium works, and expect good

editing, good lighting, good framing.

Art films have shown that it is possible

to convey a lot more through film

than meets the eye at first. More

can be expressed in good images than

words alone can convey: “you cannot

film music, but you can film musicians

and they are riveting to watch …….

there is something in the great performers

that is deeply inside them … that

wants to communicate to the public

what they feel. Some even believe

that it is their duty on earth to

create music, and that the more the

public responds, the better they get

at it”. Music, in other words, can’t

be filmed, but the artist persona

can, and this enhances the musical

experience intensely. Just as a live

recital is more than just listening,

so is filmed music.

Indeed, it was a musician who first

understood the importance of film.

It was Jacqueline du Pré herself.

Nupen recalls: “I filmed something

and said to her, “It’s not nearly

so good as when you played it on the

stage, it can’t be”. But she said

“Rubbish, you’re wrong, it’s better

on the film”. I said, “What do you

mean, better on the film, it’s nowhere

near what you did on the stage”. She

said, and I quote verbatim, “Because

you can see what’s going on and it

adds another dimension”. It took me

years to realise what she was telling

me. She was telling me, when film

is well done and artists are giving

their all, there is something radiating

that is more than just music, it is

the artistic intention of the artistic

persona and you can see it! It’s the

human element of music”.

Anyone who watches du Pré playing

pizzicato cello on the train, singing

a French folk song, can never forget

the sheer joy of playing that she

radiates. Her artistic persona is

preserved for all time. Indeed, her

enthusiasm for music must have inspired

millions of people who never met her.

It is a lasting legacy, beyond even

her wonderful performances.

Nupen adds, “There is something spiritual

in music that seems to link us to

the eternal. That sounds like a highfalutin

statement but that is what caused

Kenneth Clark to say, “Once art touches

the soul, it calls that soul back

for the rest of its days”. People

are used to the power of film. It’s

possible that the market for classical

music hasn’t even been tapped, and

could be magnified many times over

if film could be used to bring in

audiences used to watching. Once people’s

imaginations are challenged by good

films, they go onto listening further

and enjoying the experience, just

as Kenneth Clark predicted. Television

does reach these audiences. When Channel

Four presented a sixteen week retrospective

of Allegro’s work in 1993, it was

their biggest success of the year,

overall. Indeed, if anything, classical

music may even mean more in modern

society with its upheavals, because

its spiritual aspects transcend the

temporal. That’s why, says Nupen,

so many people come to music at significant

times of their lives, say, at 21,

41 or 61, when they are thinking that

there may be more to life. In an increasingly

technological and impersonal world,

the humane language of music may be

even more important than before. A

philanthropist who would sponsor classical

music and film would give society

emotional and spiritual benefit, which

would be long term and lasting.

The BBC was founded on the belief

that audiences could be “educated,

informed and entertained”. Whether

or not television still performs this

function is moot, but the power of

film to achieve these aims remains.

DVD is an even more effective medium

than television in many ways because

it’s as permanent as is currently

possible. Unlike a television programme,

it can be played over whenever you

choose. “A really good film on an

artistic subject can never be comprehended

fully in its first viewing” says Nupen,

so it pays to have something you can

revisit. Moreover, the use of chapters

enables you to return to specific

passages, just like the bookmarks

in a book. “DVD is encyclopaedic,

comprehensive and inclusive”, says

Nupen. We can turn to a DVD at any

time, for however long as we need,

and whenever we are ready, and so

much more can be included in a DVD.

Television doesn’t give the viewer

such options. Moreover, it’s “always

in a hurry”, to use Nupen’s own terms.

Everything must be produced to format,

and to deadlines which don’t allow

for the intrinsic need of artistic

innovation. Nupen and his team at

Allegro, David Findlay and Peter Heelas

have been working together for many

years. They have created extremely

high quality work. As Isaac Stern

said “Christopher Nupen’s artistic

conscience is extraordinary. He makes

the camera an instrument, not just

an observer. It is a lesson in how

alive the camera can be in response

to the inner quality of the music”.

Film is an art form, too, and Allegro

films aim for the same high standards

that the musicians they portray.

The first release in the new series

will be the seminal film “Jean Sibelius

– The Early Years - Maturity and Silence”.

It’s not a biopic, but an exploration

of the music itself, which is much

more creative and subtle. It focuses

on Sibelius’s music, and his own words.

Says Nupen, “they are extremely telling

words, extremely poetic words, extremely

deeply felt words. This man cared

more than anything else that he had

to compose music, and that he wanted

to reach people with that music ……

It’s telling the story, but it’s the

story of the work and what it has

to tell us today.” It gives remarkable

insight into Sibelius’s musical personality.

When it is released in October 2006,

it will be a major contribution not

only to Sibelius studies but to the

whole art of music appreciation.

The Sibelius film will be followed

by another great Allegro classic,

the film about Nathan Milstein. Milstein

was one of the finest violinists of

his century, acclaimed by Toscanini,

Horowitz and many others. Yet, as

Nupen recounts, “he never did one

thing to publicise his work in his

life because his mother told him,

if he publicised his work, he’d taint

his art. When Nathan died all the

musicians in the world who knew him

lamented him but there was no public

recognition, and his music was lost.

I was very lucky to get to know him,

to develop a friendship with him.

We used to have tea on Sunday afternoons.

One day, after three years, I told

him that I’d discovered that a very

early German filmmaker had filmed

Paganini in rehearsal in Frankfurt.

For a few seconds, he was startled.

And then he said “Why do you tell

me such nonsense?” And I said, “Nathan

Mironovitch, if there was film of

Paganini you were probably be first

in the queue to want to see it because

you are like that, you are more curious

than other people.” He’d once said

to me “when you stop learning, that’s

when the trouble starts!” So he said,

“Okay, you win!” and made the film.

Thus the film preserves Milstein’s

art for eternity, while Paganini’s

art is alas lost …. lost. At the age

of 82, Milstein performs with intensity,

knowing that this film will “educate,

inform and entertain” many generations

to come.

Before the age of recording, music

was live, visual and personal. Film

thus restores something of this natural

state. Just as audio recording was

an innovation in preserving performance,

audio visual recording can usher in

a new era. As performance is enhanced

by bringing in the subliminal clues

that image provides, it can develop

and expand audiences for classical

music. Being inspired by a performer

in action, picking up on nuances of

expression, as Jacqueline du Pré,

prophetically intuited, “adds a new

dimension” to the experience as a

whole.

Anne Ozorio