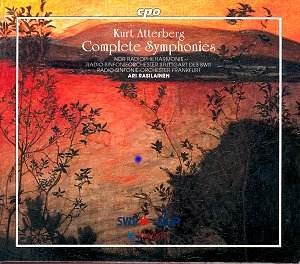

Pay-off time for those

who were prepared to ‘play the long

game’ and wait for this boxed set to

appear. CPO issued these five discs

individually at full price between 2000

and 2003. Now they appear as a bargain

set first on the shelves only a month

after the thirtieth anniversary of Atterberg’s

death.

Atterberg, a Swedish

composer, is the very model of the late-romantic

Scandinavian. Writing from the perspective

of 1974, John H. Yoell in his book ‘The

Nordic Sound’ (Crescendo Press, 1974)

said that Atterberg was "listed

among the casualties buried beneath

the avalanche of non-tonal music engulfing

the world since 1950. But tides of fad

and fashion ... did not erase what Atterberg

managed to accomplish nor quench his

impulse to keep working at an age when

most men sit rocking on the porch."

Indeed Atterberg had to contend with

another burden: that of spending a goodly

part of his very long life watching

the musical world reject his lovingly

crafted lyrical works on the waxing

moon of dodecaphony.

Atterberg’s winning

and even compelling ways show him to

be an adept of orchestral colour and

seething incident. His scores are of

the romantic-folk-impressionist type.

Yoell considered him the equal of Stenhammar

and a cut above Alfvén and Rangström.

Personally I would place him above Stenhammar

alongside a Swedish symphonist not mentioned

by Yoell but also celebrated by CPO

(and Sterling!), Wilhelm Peterson-Berger.

His biography can be

summed up rather brusquely as follows:

Initially studying as a civil engineer

and then working in the Patent Office

(1912-1940). Gave up engineering for

music. Studied with Hallén in

Stockholm. Continued his education in

Munich, Berlin and Stuttgart (the scene

of some of these recordings). Became

a solo cellist. Then took up conducting

at Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm

(1913-1922). Longstanding music critic,

writing for the ‘Stockholms Tidningen’.

Held many official posts in Swedish

musical academe and other artistic institutions.

Conducted internationally. Famously

won the Schubert Centenary Columbia

Graphophone competition with his Sixth

Symphony in 1928.

Atterberg seems to

have sided with the Nazis during World

War Two and his symphonies 7 and 8 were

premiered in Germany. This did little

to help him secure performances post-1945

when a generation of priests of dissonance

were newly risen to eminence. Atterberg’s

musical style was certainly backward-looking

and folk-centred so this approach will

have appealed to the Third Reich’s ‘establishment’.

When Atterberg recorded the Sixth Symphony,

shortly after it had won him the Columbia

competition, he went to Berlin to make

the recording with the Berlin Phil.

In all fairness we should also recall

that in Nazi Germany the most frequently

played non-German composer was Jean

Sibelius. However Atterberg’s music

has about it a lambent lyrical life

partly tapped from Swedish folk sources.

That ebullient life transcends the sympathy

it evoked from Nazi sources.

Atterberg's symphonies

on record have, until CPO and Ari Rasilainen

set about them, been patch-worked across

labels. No. 2 on Swedish Society Discofil.

No. 3 on Caprice (still a very fine

recording by the way). Nos. 1 and 4

on Sterling. No. 6 is multiply recorded

on dell'Arte, Koch and most accessibly

on Bis. Numbers 7 Romantica and

8 are also on Sterling. We should remind

ourselves that the CPO cycle while premiering

on record only the Ninth presents in

most cases only the second CD

appearances of all these works and the

first in full digital format (excepting

only 3, 6, 7, 8).

CPO Disc 1 couples

symphonies 1 and 4; the selfsame works

harnessed on Sterling CDS-1010-2 at

full price. Sterling rescued an LP recording

of the Fourth Symphony from oblivion

and coupled it with the First Symphony

- the results of sessions in the Berwald

Hall, in Stockholm on 3-5 November 1986.

One difference between the two recordings

is that Frank Hedman who produced the

Sterling discs back in 1989 streamed

the Adagio and Presto of

the First Symphony together into a single

track (tr. 2) while CPO keep the two

separate. The Fourth had been recorded

back in 1976 in Norrköping where

the control room was in the hands of

a certain Robert von Bahr now better

known now as the presiding angel of

BIS. Sterling were unable to track down

the master-tape of the Fourth Symphony

so what we hear is overdubbed from a

vinyl disc.

The Sterling First

Symphony is conducted by Stig Westerberg

and the orchestra is the Swedish Radio

Symphony. The timings of the two versions

are only minutes apart with Westerberg

being a few seconds quicker than Rasilainen.

This work is a lanky great 40 minute

symphony full of Rimskian colour, subtle

textures, heroic turbulence akin, in

the tempestuous finale, to Howard Hanson’s

first two symphonies. When the supremely

confident French horns sing out in Tchaikovskian

warmth over the top of the aspiring

strings (at the climax of the finale)

you know that you are confronting a

seriously-intentioned symphonist. You

also know that the CPO engineers have

done well to capture such virile playing

with natural fidelity. Both versions

are good at putting across the exhilarating

spasm and majesty of the final five

minutes. The only differences I noted

between the two versions was that the

violins of the Frankfurt orchestra sounded

sweeter than those of Swedish Radio

and generally there seemed a more naturally

spacious effect on the CPO. It was,

after all, made fourteen years after

the Sterling sessions. Otherwise there

is little to choose between the two

except of course that the Sterling is

at premium price.

The Fourth Symphony

was completed in 1918, the same year

that Atterberg finished his first opera,

Hårvard Harpolekare. It is splashed

with many Sibelian touches especially

in the bristling tense high writing

for violins redolent of the Finn’s light-suffused

Sixth Symphony itself recorded by Georg

Schneevoigt who in 1919 premiered the

Atterberg in Stockholm.

The Fourth is much

more concise than the First and runs

to just over twenty minutes. Sten Frykberg

for Sterling is perhaps a minute quicker

overall. The spirit of folksong is there

in full and a life-enhancing tune courses

through the first movement. The andante

second movement is simply magical

with a Grainger-like folk-tune intoned

smoothly and lovingly by the clarinet

over the gossamer glow of ppp

strings - we will meet that effect again.

In the Sterling version such is the

whisper-quiet of the music you can hear

the light bristle of groove noise both

here and in the finale. The scherzo

is all over in less than 1½ minutes

recalling, along the way, Dvořák’s

New World. It ends with a veritable

wink.

Rasilainen is a mite

more heavy-handed than Frykberg who

is closer to the music’s Mendelssohnian

faery-lightness and strangely enough

his sound-stage is kinder to this spirit

than the grand hall ambience achieved

by Hessischer Rundfunk for CPO. The

finale is lively with the Swedish equivalent

of a lesghinka and the stompingly triumphant

dances that Atterberg became adept at

turning to symphonic gold in his finales.

Listen to the way the orchestra’s leader

launches and sustains a touchingly yielding

obbligato half sob, half cry at ppp

at 2:45 continuing for many bars. The

exuberance and exhilaration of the finale

recalls Lemminkainen’s Homecoming,

Smetana’s Bartered Bride furiants

and Rimsky’s Capriccio Espagnol.

The piece ends with the usual affirmative

blows topped off with a high squeal

from the first violins. This sounds

for all the world like the village fiddlers

dashing off one last stratospheric stab

and slash with the triangle resounding

as the dancers fall exhausted to the

floor. A lovely work this. Some vinyl

wear can be heard in the demanding finale

of the Symphony in the Sterling version.

No such problem in the CPO.

The second disc couples

symphonies 2 and 5. The Second Symphony

was recorded by Stig Westerberg

in October 1967 and first issued on

LP SLT 33179. It runs to 39:19 as against

Rasilainen’s 41:00. The Westerberg is

on Swedish Society Discofil CD SCD1006

and is coupled with Atterberg’s famous

Suite No. 3 for violin, viola and strings;

itself the acme of the Nordic crepuscular

romance and not to be missed. Rasilainen

clearly warms to the beauty of this

softly singing music contrasted with

a slammingly sanguine epic-triumphant

spirit. His version reminded me at times

of Howard Hanson’s First Symphony Nordic

which dates from about eight years

after the Atterberg. The Westerberg

still sounds the business but his violins

while having a more supple victory in

their weight lack the silky gleam of

the Hannover NDR orchestra nor does

the brass sound as cleanly emphatic

and free from that hint of surface spall.

Interestingly the music reminded me

occasionally of Richard Strauss and

in the swooning ebb and flow of the

first movement of Louis Glass’s masterful

Symphony No. 5 Sinfonia Svastica

again lying about eight years in the

future. Westerberg scores for additional

hushed enchantment in the wonderful

Adagio.

The Fifth Symphony

is the Sinfonia Funebre.

It may be dark but it doesn’t sound

funereal to me. In the Fifth’s first

movement there is a prominent part for

orchestral piano. This is a most impressive

movement with strong Sibelian credentials

- music of bardic surging confidence

likened to the first movements of the

Stenhammar Second Symphony and the Moeran

G minor Symphony as well as the finales

of the first four Joly Braga Santos

symphonies. Before Atterberg succumbs

to a lush Korngoldian luxuriance in

the second movement he write music that

links directly with Nystroem’s much

later Sinfonia del Mare in its

magical redolence of the endlessly murmuring

sea miles. This is saturatedly romantic

material and its neglect in the face

for example of the understandable popularity

of Rachmaninov’s Second Symphony is

incomprehensible. The finale has a fugal

character and there is some wonderfully

pointed fast writing for the violins

at 5:20 on CPO. Again the piano adds

another voice to the texture. It is

oddly in tempo di valse with

possibly a cloaked reference to Sibelius’s

Valse Triste and even to the

eruptively orgasmic pages of Ravel’s

La Valse. Samuel Barber, many

years later, does something similar

in the orchestral version of the Tango

from Souvenirs. This waltz

can also be compared in subtlety with

its use by Prokofiev who infuses a psychological

message - here the ‘strapline’ is one

of brooding and inimical fate. At 12:10

there is a return to the intimately

consolatory rocking motif noted before

as a precursor to the Nystroem Sinfonia

del Mare here touched with the passion-spent

exhaustion of the finale of Tchaikovsky’s

Pathétique. The Symphony

ends in a quietly dismissive pizzicato

- almost impassive. Both Rasilainen

and Westerberg are impressive. Westerberg’s

engineers lent his recording an additional

cosiness that perhaps slightly muffles

the many instrumental strata.

Westerberg conducts

the Stockholm Philharmonic on Musica

Sveciae MSCD620 recorded in August 1990.

He brought out for me the fury of the

writing in the first movement just as

much as Rasilainen. Incredibly some

of this prefigures Vaughan Williams’

snarling Fourth Symphony from a decade

later. Once again there is little difference

between the timing adopted by the two

men.

The Third Symphony

is in the usual three movements.

Subtitled West Coast Pictures this

is a classic of Scandinavian marine

poetry. It’s the place to start any

exploration of Atterberg. The music

is copiously romantic but here delicate

and limpid impressionism is an important

element. This is the most impressionistic

of all the Atterberg symphonies. The

murmurous first movement Sun Haze

once again predicts Nystroem's Sinfonia

del Mare and unknowingly parallels

Bax's Tintagel. Storm

is the central movement. There's a real

surging urgency about this music which

crashes, swells and thunders in oceanic

glory. Wonderfully raw and brawnily

Odyssean writing for the horns adds

distinctively to the aural pantone.

The schema of the piece is worth noting:

two largely placid and poetically self-absorbed

movements flanking a feral storm.

Ehrling's pioneering

version with the Stockholm Phil on Caprice

CAP21634 can still be had. It is very

effective and lovingly recorded. Ehrling

is a minute or so brisker than Rasilainen

in the outer movements. But frankly

Rasilainen's slower pacing suits the

music better in those movements. Try

the great slow unleashing of the world-conquering

melody at 4:09; why are we not hearing

this at the Proms? CPO's recording is

also more attentive to detail. Time

after time solos emerge with greater

command. Were this a one-to-one confrontation

I would still prefer Rasilainen. As

it is, this CPO set is available

at what amounts to bargain price per

disc for the complete cycle. I would

not want you to miss even one of

these fine symphonies.

The Sixth Symphony

has had reams written about it most

of which detracts from its considerable

intrinsic attractions. The tripartite

movement pattern is followed. Once again

Rasilainen is faster than the main modern

competition (we'll ignore Beecham and

Toscanini). That competition is from

Jun'Ichi Hirokami and the Norrköping

orchestra on BIS-CD-553. Bis or Hirokami

failed in their courage and so the coupling

there is not one of the other symphonies

but A Vårmland Rhapsody and

Ballad Without Words. Even so

Hirokami's reading and Bis's refined

and highly detailed recording is not

to be dismissed easily. You just have

to listen to the hushed enchantment

of the start of the middle slow movement

and Johnny Jannesson's clarinet solo

to know that you are in the presence

of estimable music-making. CPO, by contrast,

have one of Atterberg's finest symphonies

as a coupling: No. 3. Apart from some

false-sounding braggartry in the first

and last movements the whole of the

Sixth works well as another example

of Atterberg's folksy-poetic drama.

Folksong always buoys up his inspiration

as in that sad-joyous clarinet solo

in the Adagio. To a lapidary diaphanous

ostinato Atterberg delivers yet more

fine melodic inspiration in the finale

with Mahlerian grandeur being not a

stone's-throw away.

If you were considering

buying CPO 999 641-2 (symphonies 7 and

8) by itself it would be up against

direct competition from Sterling CDS-1026-2

(Malmö SO/Michail Jurowski). In

both works Rasilainen is not in fear

of pushing forward. He is almost five

minutes faster than Jurowski in No.

7 (four of those five minutes quicker

in the big Drammatico first movement).

In No. 8 he is three minutes shorter.

After the Mahler 5-style

start of the Sinfonia Romantica

(No. 7) there is the usual fine

skein of folk-accented melodic impressionism.

The finale is almost warlike (rather

like Bax's Northern Ballad No. 1)

and the music takes on the character

of a crushing giant's jig with some

rawly raucous work delivered from the

brass benches. On balance the Sterling

is probably more sumptuously recorded

not that the CPO is not excellent.

The Eighth Symphony

is

an exercise in joyous folk grandeur

- in fact Atterberg in this mode strikes

me as the Scandinavian Dvořák.

His treatment of simple folk melodies

is always dignified and never pompous.

He excavates the latency each folk dance

and song has for the epic and for dramatic

effect. In this work he makes delightful

use of pizzicato and woodwind in a way

familiar from Sibelius in The

Tempest written two decades earlier.

In the finale the main theme sounds

a little like 'There was a jolly miller

once ...' Intriguingly the stuttering

trumpet motif from the start of Mahler

5 (already noted in the Atterberg Seventh)

can also be heard in the background

in the finale of Atterberg 8 (tr. 7

7:55 on CPO). Also very obvious are

the passing quotes, in the first movement

of No. 8, to the Schubert Great C

major (tr.4 1:58 Sterling). The third

movement molto vivo reminds me

of Sibelius's lighter theatre music

mixed with Mahlerian ländler. Then

again Atterberg

rises to a syncopated majesty at 1:08

(tr. 6) that transcends any influences.

There are regal moments in Dvořák

7 and 8 that this at the very least

equals: that's how good this music is.

Back to comparisons:

once again the Sterling coupling including

No.8 shades the CPO in refinement and

transparency of sound. Then again the

second movement in Jurowski's hands

is taken a mite too languidly - the

bassoon and cuckooing flute almost coming

to a standstill - although it does make

mesmerising listening.

And now to the final

disc; the only one I have reviewed to

date.

After the strongly

tuneful Nordic romantic-impressionism

of the earlier scores some listeners

are in for a culture shock with the

Ninth Symphony. All the auguries

are promising. The text is from the

Voluspá ('The Face of the Prophetess'),

part of the Icelandic Edda - a creation

epic. The Vanir and Aesir are mentioned

in the sung text as are Odin, Midgård,

Yggdrasil, Heimdall, Thor, Loki and

Frigg. Is this going to be a vivid nationalistic

score? Well actually, no. The contours

undulate, the approach is narrative

rather than dramatic and the music is

sombre, concentrated, serious and broad.

It is determinedly tonal but it is as

if the composer no longer sees any compulsion

to create magical effects or diaphanous

brilliance. It is predominantly meditative

music with animation only entering in

Med spjut sprängde Oden, Rym

styr un östern and Nu stundar Friggas

movements (trs. 6, 11, 12 - the latter

two being choral). The Symphony ends

after the words:-

"The sun blackens

the land sinks into the sea

The sun blackens

winter's frost in summer

From heaven fall

flaming stars.

...

Much I've experienced

I see far into the future

...

Now the Vala is silent."

Certainly a downbeat

ending ... 'not with a bang but a whimper'.

None of the visionary exaltation of

Rosenberg's Johannes Uppenbarelse,

Martinů's Epic of Gilgamesh

nor the monumentalism of Goossens'

Apocalypse or Schmidt's Book

with Seven Seals.

The performance history

of this Ninth has been predictably sparse.

The premiere was given in Helsinki in

1957 when the conductor was Nils-Erik

Fougstedt and the orchestra was the

Helsinki Symphony. There was a performance

in Dortmund in 1962 and another in Göteborg

in 1975 on the anniversary of the composer's

death. A tape of the 1957 premiere gave

the symphony a kind of half-life on

the tape underground. Michael Kube's

note is typically helpful and provocative

comparing Visionaria with Karl

Weigl's Apocalyptic Symphony;

Korngold's Symphony in F sharp and Hindemith's

Die Harmonie der Welt. The booklet

prints the full text as sung and in

English and German translation, side

by side.

As a balm to those

bruised by the sustained sobriety of

the Ninth Symphony, Älven

- från fjällen till havet

(The River - from the Mountains

to the Sea) is a symphonic poem

written in the wake of the worldwide

success of the Sixth Symphony. It was

commissioned by the Göteborg Orchestral

Society (who revived it in the 1980s

with Norman del Mar). It is in seven

continuously-played episodes: Through

mountains and forests; The great

lake; The waterfalls; The

quiet, wide stream; The harbour;

View from the mountains over the

sea; Out to the sea. There

is an even more detailed verbal account

given by the composer and quoted in

the booklet. The musical idiom is comparable

with the Third Symphony - alive with

colour and contrast as well as being

rich in melodic resource. The music

moves through cinematic grandeur to

impressionistic filigree (à la

Bantock's Pierrot of the Minute),

to malcontented nightmare rising to

a deeply impressive rolling brass theme

- more Korngold than Strauss (tr.16).

Restless activity is punctuated with

a jerkily emphatic romantic motif that

suggests the Third Symphony (West

Coast Pictures). The star-glimmer

of The Harbour is made distraught

with some very 'modern' wailings and

groans (Ruggles and Varèse perhaps).

These give way to an unusually twee

Swedish folksong and then to the Delian

nobility of the view from a mountain

eminence across the sea's miles. In

the final episode the sea shouts in

a triumph touched on in the Third Symphony;

compare also the gale in Bax's November

Woods.

The CPO cycle of symphonies

can still be purchased separately but

at this price why sample. However here

are the details if you need them:-

Numbers 1 and 4 CPO

999 639-2

Numbers 2 and 5 CPO

999 565-2

Numbers 3 and 6 CPO

999 640-2

Numbers 7 and 8 CPO

999 641-2

Number 9 and Älven

CPO 999 913-2

This is the first cycle

on one label, by one conductor but with

orchestral service divided between two

orchestras: Radio-Sinfonie-Orchester

Frankfurt, Radio-Philharmonie Hannover

des NDR, SWR Radio-Sinfonieorchester

Stuttgart.

Rasilainen inspires

his orchestras to readings of great

intensity and poetry. If you read some

of the Atterberg literature you might

easily misread these symphonies as pictorial,

shallow, technically accomplished but

without depth and far too reliant on

borrowed folk tunes rather than his

own inspiration. Both in hearing these

readings and the preparation I made

in advance by listening to the other

recordings of the first eight symphonies

I have no doubt that Atterberg has every

right to stand with such symphonists

as Bax, Ropartz (whose five are rumoured

already to be ‘in the can’), Moeran,

Stenhammar and Louis Glass. He is a

supremely imaginative virtuoso writer

for the orchestra and his sense of symphonic

trajectory, mood and scenario matches

his extraordinary technical gifts. His

inspirations are of the finest quality

and if he relies on folk material it

is adeptly resolved into the symphonic

fabric rather than seeming to be grafted

on.

The complete Atterberg

symphonies? Well, not quite. It’s a

bit like Malcolm Arnold in fact. Atterberg

wrote nine numbered symphonies. Arnold

wrote nine numbered symphonies. Both

wrote a Symphony for Strings but unlike

Karl Amadeus Hartmann and William Schuman

they did not include them in their numbered

canon. This has tended to leave both

works out in the cold. As it is, the

Atterberg has never been commercially

recorded although an athletic and exciting

radio studio recording (S-A Axelsson

and Malmö Radio Orchestra) has

for many years done the rounds among

tape and CDR collectors. It was a lost

opportunity that it was not added to

the Visionaria disc instead of

the symphonic poem. All in due time.

There is plenty more Atterberg to be

recorded. There is for a start the awesomely

attractive Three Nocturnes from

his ‘Arabian Nights’ opera Fanal;

not to mention a systematic recording

of the nine orchestral suites. We have

most of the concertos but let’s not

forget the Double Concerto (violin and

cello). And that’s without looking at

a Requiem, two string quartets, four

ballets, and five full-length grand

operas: Hårvard Harpolekare

(1918, Harvard the Bard),

Bäckahasten (1925), Fanal

(1934 - given the extraordinary

quality of the Three Nocturnes this

should be revived first), Aladdin

(1941 - yes, the very same Oehlenschlager

drama that inspired Nielsen in his incidental

music and Busoni in the finale the Piano

Concerto) and The Tempest (1948).

As an anhang to this

set don’t forget CPO 999 732-2 which

has the Piano Concerto; Rhapsody; Ballade

and Passacaglia. However if you are

curious about the Piano Concerto you

can also hear it in a more substantial

coupling on Sterling CDS-1034-2 coupled

with the Violin Concerto (1913-14).

So far as presentation

is concerned the set simply fits the

five individual CDs as issued into a

light card slip case. This tends to

be CPO’s practice - compare their Korngold

and Frankel symphony sets. This differs

from the practice of BIS who usually

repackage such sets (Alfvén symphonies,

orchestral music of Stenhammar, Nielsen

symphonies and Vänskä’s Sibelius

symphonies) into slimmer line multi-CD

boxes with a new booklet. I have no

substantial complaints about CPO’s decision;

certainly not at this price - in the

UK £25:50 for 5 discs.

For now we should focus

on having such a sympathetically recorded

and magnificently conducted cycle at

our finger tips in return for what amounts

to Naxos price for the five discs. To

enthusiasts who in the 1970s and 1980s

moved heaven and earth, bank balances

and tape machines to get to hear the

full cycle this box represents riches

unimaginable.

Rob Barnett

COMPARATIVE REVIEWS OF THE CPO ATTERBERG

SERIES as they were released.

All very well worth reading. However

do take time to have a look at Lewis

Foreman’s highly informative reviews

especially the review of symphonies

3 and 6 as well as at Ian Lace’s vividly

descriptive general article on Atterberg.

My recommendation is that you start

with the Third Symphony and then find

your own way reserving 9, 5 and 4 towards

the end of the listening experience.

Ian Lace on Kurt Atterberg

http://www.musicweb-international.com/film/2000/mar00/ifonly.htm

Symphonies 1 + 4. CPO

http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2000/apr00/atterberg.htm

Symphonies 2 + 5. CPO

http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2001/Jan01/atterberg.htm

Symphonies 3 + 6. CPO

http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2001/Jan01/atterberg.htm

Symphonies 7 + 8. CPO

http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2001/Dec01/Atterberg78.htm

Symphonies 9 + Älven. CPO

http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2003/Nov03/Atterberg9.htm

http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2003/Sept03/atterberg9.htm

Piano Concerto. CPO

http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2002/Mar02/Kurt%20ATTERBERG.htm

Concertos: Violin; Piano - Sterling

http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/nov99/atterberg.htm

http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/oct99/atterberg.htm