The idea of chamber

music generally bespeaks a certain intimacy

of scale - not one of Anton Bruckner's

conspicuous strengths. Indeed, to all

intents and purposes, the F major Quintet

is simply another of the devout Austrian's

heaven-storming symphonies, decked out

in minimal instrumental garb. The composer's

standard harmonic and structural tics

all come into play: the emphatic octave

climaxes, the harmonic pivots from flat

keys into distantly related tonal regions

in sharps, the codas emphatically banging

away at the tonic chord. And, at forty-five

minutes and change, the piece is of

comparably symphonic duration as well.

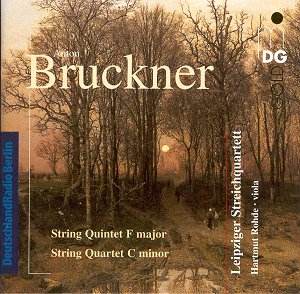

The Leipzig Quartet

members, and their guest violist, acknowledge

the scope of this music with a big-boned,

firm-bowed sound, providing even the

semiquavers a sense of breadth, and

infusing the moving parts in the chorales

(as at the Adagio's opening)

with full tonal weight. They understand

the music's proportions, eliciting expression

from details, but never to the detriment

of the music's long, arching structures.

Their intonation is consistently impeccable:

the most tortuous harmonic side-steps

are "placed" precisely, while simple

passages in thirds sing vibrantly. And,

while the players know how to project

the music's lyric grandeur, they don't

neglect the relaxed, rustic charm of

its Austrian folk elements.

Against this, an erratic

attitude to dynamics is a small but

definite minus. Bruckner, as an organist,

knew how to use terraced dynamics for

dramatic effect, and did so extensively:

the score abounds in sudden drops to

piano or pianissimo. Sometimes,

when all five players make the adjustment

(as at 4:32 in the Adagio), the

effect evokes the awe the composer surely

meant to suggest. But other such opportunities

are completely missed, with no audible

change at all (at 0:59 and again at

5:47 of the Scherzo). In still

other places, leader Andreas Seidel

gets markedly softer than everyone else,

so the desired contrast is indicated

rather than fully realized.

And the playing, sturdy

and dead in tune as it is, isn't really

suave. Seidel's tone can be momentarily

grainy at the start or end of phrases.

Solo second violin passages expose Tilman

Büning's scrawny, whitish sound

- though, given the frequent violin

part-crossings, this actually helps

the ear distinguish the voices. And

cellist Matthias Moosdorf hammers away

overbearingly at the first-movement

coda's repeated Fs. But the players'

fervent commitment ultimately convinces.

Besides, modern alternatives aren't

exactly thick on the ground. L'Archibudelli's

Sony recording is excellent, but they're

"period" players who use gut strings,

to lovely but markedly different effect.

The C minor Quartet,

a student work with a strongly classical,

Beethovenesque profile, stands in the

same relation to the Quintet that the

F major "Study Symphony" - the one the

French call "Double Zéro"

- does to the canonical symphonies.

Still, the second subject of the opening

Allegro moderato evinces some

of the familiar liquid misterioso

quality, with the occasional moment

of soaring lyricism hinting at the beauties

to come. I didn't have access to a score

to check on dynamics, but I doubt this

early work calls for many sudden level

changes, and the players certainly sound

fine.

Stephen Francis

Vasta