The thirty-nine operas

of Gioachino ROSSINI

(1792-1868)

A conspectus of their

composition and recordings

Part 2

Back in Naples impresario Barbaja wanted

something musically different and scenically

spectacular from his contracted composer

for the re-opening of the rebuilt San

Carlo with its new state of the art

stage facilities. Rossini obliged with

his 22nd opera, Armida.

An included fourteen-minute ballet was

good practice for Rossiniís later Paris

works where a ballet was de rigueur.

In fact Rossini produced his most romantic

opera to date in terms of the opulence

of the music including three extended

love duets. The libretto called for

lavish staging including Armidaís palace

and enchanted garden. There was to be

much comings and disappearances as well

as dances by nymphs, cherubs and dragons.

The lovers Armida and Rinaldo descend

on a cloud that becomes her chariot

and, as she waves her wand, turns into

her castle. Despite the spectacle of

the production, the opera was only moderately

well received. The contemporary critical

opinion was that the music was Ďtoo

Germaní; the implication was that it

was too romantic in the manner of Weber.

The requirements for the staging of

the work restricted its spread although

it found favour in Germany. By the end

of the 1830s it had disappeared, only

re-emerging as a vehicle for Callas

at the 1952 Maggio Musicale in Florence.

Added to the complications and cost

of staging the work is the requirement

of six tenors and much high tessitura,

albeit with the prospect of doubling.

The sole female  role

is that of Armida. At the premiere Isabella

Colbran sang the role. She was shortly

to become Rossiniís wife, which may

account for the inspiration for some

of his most voluptuous music. The well

recorded bargain-priced Arts performance

(review)

under the idiomatic and scholarly baton

of Claudio Scimone makes the most of

Rossiniís mature music whilst the well

cast soloists make the most of their

bravura opportunities without succumbing

to vocal excess; a highly recommendable

recording.

role

is that of Armida. At the premiere Isabella

Colbran sang the role. She was shortly

to become Rossiniís wife, which may

account for the inspiration for some

of his most voluptuous music. The well

recorded bargain-priced Arts performance

(review)

under the idiomatic and scholarly baton

of Claudio Scimone makes the most of

Rossiniís mature music whilst the well

cast soloists make the most of their

bravura opportunities without succumbing

to vocal excess; a highly recommendable

recording.

Even by Rossiniís standards the time

between the premiere of Armida

in Naples and that of Adelaide

di Borgogna (No. 23) at the

Teatro Argentina in Rome on 27th

December 1817, was short. He is thought

to have composed the opera in less than

three weeks. Aged 25 and with Isabella

Colbran, the diva of Naples his mistress,

he was certainly working and playing

hard. With only slight alteration to

the orchestration he re-used the overture

from La Cambiale di matrimonia (No.

2) but lavished his efforts on the choral

writing. Currently the Fonit Cetra recording

conducted by Alberto Zedda is not available,

but Opera Rara performed and recorded

the work at the 2005 Edinburgh Festival.

Back in Naples, Mosé in

Egito (No. 24) was premiered

on March 5th 1818. Even the

stage facilities at the refurbished

San Carlo could not portray a realistic

parting of the Red Sea. The work was

an immediate success. Mosesís act 3

prayer Díal tuo stellato soglio,

with accompanying chorus, has become

a firm favourite among basses. Although

uneven in some of the solo singing,

the 1981 Philips recording with Ruggero

Raimondi as Moses, conducted by Claudio

Scimone, is a worthy representation

of the work. This recording is of the

1819 revision which is somewhat expanded

from the 1818 premiere. Rossini made

greater revisions when he presented

the work in Paris, in French, in 1827

as Moïse et Pharaon (No.

37, see below). Translated into Italian

this is the basis of an abridged version

of a live Munich performance (Orfeo

C5149921) and an earlier studio recording

conducted by Gardelli on Hungaroton

(HCD 12290-92).

After Mosé Rossiniís only composition

that year was his last one act farse,

Adina (No. 25). This was

a private commission by the son of the

Lisbon Chief of Police. Rossini composed

the work whilst on a visit to his parents

in Bologna in the summer of 1818. It

was not staged until 1826.

On return to his Naples base, Rossini

presented Ricciardo e Zoraide,

(No. 26) on December 3rd.

It was the fifth in the sequence of

nine opera seria he wrote for that city.

Although the libretto has been criticised,

Rossiniís music is innovative and dramatic

with that written for Colbran and the

two Naples tenors, Andrea Nozzari in

the role of Agorante and Giovanni David

as Ricciardo being both florid and dramatic.

The work was well received at its San

Carlo premiere, and later revival, as

well as when seen in  Paris,

Lisbon, Munich and elsewhere. It was

regularly performed until 1846 when

it disappeared from the repertoire until

it was revived at Pesaro in 1990. The

1995 Opera Rara recording (review)

features the tenors Bruce Ford and William

Matteuzzi who portrayed their roles

at Pesaro. The two tenors are particularly

fine in meeting the demands of their

roles as are Nelly Miricioiu as Zoraide

and Della Jones as Zomira. A highly

recommendable recording whose engineering

and conducting matches the quality of

the singing.

Paris,

Lisbon, Munich and elsewhere. It was

regularly performed until 1846 when

it disappeared from the repertoire until

it was revived at Pesaro in 1990. The

1995 Opera Rara recording (review)

features the tenors Bruce Ford and William

Matteuzzi who portrayed their roles

at Pesaro. The two tenors are particularly

fine in meeting the demands of their

roles as are Nelly Miricioiu as Zoraide

and Della Jones as Zomira. A highly

recommendable recording whose engineering

and conducting matches the quality of

the singing.

On March 27th 1819, three

months after Ricciardo, Rossini presented

Ermione (No. 27) at the

San Carlo. The libretto is based on

Racineís great tragedy Andromaque.

The eminent Rossini scholar, Professor

Philip Gossett, considers if Ďone of

the finest works in the history of 19th

century Italian operaí. The Naples audience

were not impressed and it was next heard

in a concert performance in 1977. It

was staged at Pesaro in 1986 with Montserrat

Caballé a formidable heroine.

I personally find the work lacks the

drama and fluidity of Ricciardo.

Nonetheless, I derive much enjoyment

from my 1977 Erato recording (ECD 75336)

conducted by Scimone and with Cecilia

Gasdia as Ermione and featuring the

specialist Rossini tenor duo of Chris

Merritt and William Matteuzzi.

On 24th April 1819, within

a month of the premiere of Ermione,

Rossini presented Eduardo e Cristina

(No 28) at the Teatro San Benedetto,

Venice. In this instance it was not

a question of Rossiniís felicitous capacity

for speedy tuneful composition. Nineteen

of the twenty-six numbers in the opera

were taken from earlier works and a

previous libretto was revised to accommodate

the music! The concoction was a huge

success. The audience at the premiere

encored several numbers and twenty performances

were given in the season. The following

year the work transferred to the La

Fenice, Veniceís premier house. There

were also productions in other cities

although by 1840 it had fallen from

the repertoire. I know of no recordings

of the work.

On his return to Naples in the summer

of 1819 Rossini presented La donna

del lago (No. 29) on 24th

September. It was the first opera to

be based on any of Walter Scottís romantic

works. Although the most famous in our

time is Donizettiís Lucia di Lamermoor,

Scottís popularity as a source of operatic

libretti expanded rapidly after Rossiniís

example. By 1840, a mere 21 years after

La donna del lago, there were

at least 25 Italian operas based on

Scott plus others by German, French

and English composers. Although none

of Scottís works had been published

in Italian at the time, Rossini had

read The Lady of the Lake in

French translation and been inspired

by it. At the premiere on September

24th the opera had a lukewarm

reception that warmed at subsequent

performances. The work remained in the

San Carlo repertory for a further twelve

years and within five years of its composition

it was heard all over Italy and in Dresden,

Munich, Lisbon, Vienna, Barcelona, St.

Petersburg, Paris and London. The Act

2 rondo, Tanti affeti, roused

Naples audiences when sung by Isabella

Colbran. By  1860

the work was forgotten until its revival

in Florence in 1958. It was performed

and recorded live at Pesaro in 1983.

The recording features Katia Ricciarelli

as Elena, Lucia Valentini Terrani as

Malcolm and Samuel Ramey as Douglas

in a very affecting overall performance

(CBS Masterworks. M2K 39311). The reviewed

mid-price Opus Arte DVD (review)

is of the rather dark 1992 La Scala

staging which lacks any particular Scottish

focus. June Anderson sings with good

firm tone and coloratura. Her tanti

affeti is enthusiastically received.

She also duets well with the creamy

toned Martine Dupuy in the trousers

role of Malcolm. Mutiís conducting draws

the best from what is one of Rossiniís

most inspired and innovative opera seria

scores. There is also an audio recording

from this series of La Scala performances

(Philips 438-211-2).

1860

the work was forgotten until its revival

in Florence in 1958. It was performed

and recorded live at Pesaro in 1983.

The recording features Katia Ricciarelli

as Elena, Lucia Valentini Terrani as

Malcolm and Samuel Ramey as Douglas

in a very affecting overall performance

(CBS Masterworks. M2K 39311). The reviewed

mid-price Opus Arte DVD (review)

is of the rather dark 1992 La Scala

staging which lacks any particular Scottish

focus. June Anderson sings with good

firm tone and coloratura. Her tanti

affeti is enthusiastically received.

She also duets well with the creamy

toned Martine Dupuy in the trousers

role of Malcolm. Mutiís conducting draws

the best from what is one of Rossiniís

most inspired and innovative opera seria

scores. There is also an audio recording

from this series of La Scala performances

(Philips 438-211-2).

Immediately after seeing La donna

del lago staged in Naples, Rossini

went off on one of his frequent absences

to present an opera during the carnival

season at La Scala, Milan. Felice Romani

was on hand to provide the libretto

and Bianca e Falliero

(No. 30) was premiered on December 26th

1819. The work was performed thirty

times during the season and soon spread

throughout Italy and beyond before disappearing

after 1846. It  was

revived at Pesaro in 1986 with Katia

Ricciarelli, Marilyn Horne and Chris

Merritt. The Fonit Cetra recording from

those performances is not currently

available. The Opera Rara recording

(review)

made in November 2000 with Majella Cullagh

as the heroine and Jennifer Larmore

as her lover is an outstanding success

in all respects. The duets between the

two exhibit bravura coloratura singing

of the highest order. The rest of the

cast, conductor and engineering match

this standard.

was

revived at Pesaro in 1986 with Katia

Ricciarelli, Marilyn Horne and Chris

Merritt. The Fonit Cetra recording from

those performances is not currently

available. The Opera Rara recording

(review)

made in November 2000 with Majella Cullagh

as the heroine and Jennifer Larmore

as her lover is an outstanding success

in all respects. The duets between the

two exhibit bravura coloratura singing

of the highest order. The rest of the

cast, conductor and engineering match

this standard.

Another twelve months were to pass

before Rossini presented his next opera,

Maometto II (No. 31).

It was premiered in Naples on December

3rd 1820. This interregnum

between Rossiniís operatic compositions

was connected to personal and political

consideration rather than compositional

inertia or block. Early in the year

he presented an opera by Spontini at

the San Carlo and wrote his Messe

di Gloria. Isabella Colbran, the

lead soprano at the San Carlo, and Rossiniís

mistress, who was to sing Anna Erisso

at the premiere had to return home to

Spain for a period on the death of her

father and to arrange the transfer of

his estate to her. More importantly

civil unrest broke out in Naples with

a group of army officers and priests

leading an uprising against the King

and threatening revolution if he did

not proclaim a constitution. Gunboats

from Britain arrived in the Bay of Naples

and the Austrian army marched in to

provide the King with some backbone.

Rossini is reputed to have served for

a short period in the guardia nazionale

during this period. Maometto II was

received only modestly in Naples. The

recently re-issued Philips 1983 recording

(Decca 475 509 2) conducted by Claudio

Scimone, with Samuel Ramey in the title

role and June Anderson as Anna, reveals

a work of  considerable

dramatic and musical intensity. Rossini

rewrote the work as La Siège

de Corinthe (No. 36) for his Paris

Opera debut in 1826. He also made a

shortened version for performances at

Veniceís San Benedetto theatre in 1822.

This shorter version was performed at

the 2002 Bad Wildbad Festival and recorded

by Naxos (review).

A World Premier Recording, the live

concert is well caught by the engineers,

vibrantly conducted and with the young

singing cast distinguishing themselves.

considerable

dramatic and musical intensity. Rossini

rewrote the work as La Siège

de Corinthe (No. 36) for his Paris

Opera debut in 1826. He also made a

shortened version for performances at

Veniceís San Benedetto theatre in 1822.

This shorter version was performed at

the 2002 Bad Wildbad Festival and recorded

by Naxos (review).

A World Premier Recording, the live

concert is well caught by the engineers,

vibrantly conducted and with the young

singing cast distinguishing themselves.

After the premiere of Maometto,

Rossini went to Rome where he had agreed

to write a new work for the Teatro Apolloís

carnival season. Problems with the libretto

left Rossini with little time and he

enlisted composer colleague Pacini to

assist him by writing three numbers.

Matilda di Shabran (No.

32) was presented on 24th

February 1821. The work had a mixed

reception but quickly spread to other

Italian cities. It reached London in

1823 and New York in 1834. Juan Diego

Florez saved its premiere at Pesaro

in 1996. He jetted in to replace the

indisposed scheduled tenor and subsequent

stardom. He also sang in a new production

at the festival in 2004. It may be that

a CD or DVD of the performance will

be issued. It would be particularly

welcome as a very good all-round cast

also included the delectable Annick

Massis as Matilde. I know of no other

recording.

Back in Naples Rossini found that Barbaja

had arranged for the whole of the company

of the San Carlo to stage a season in

Vienna where Rossini was already the

favourite opera composer. Weberís Der

Freischutz was included in the San

Carlo season alongside six Rossini operas

including Zelmira (No.

33) which had been premiered in Naples

on February 16th 1822. With

Vienna in mind, Rossini took great care

with its composition, but the plot did

not lend itself to success in Naples.

Claudio Scimone praised the score after

conducting it in Venice in 1988, performances

which form the basis of the Erato studio

recording made in London the following

year (2292-45419-2). In the recording

the three tenors are nicely contrasted

and appropriately expressive in the

demanding fioritura. On the distaff

side Cecilia Gasdia in the name part

is well matched by mezzo Bernarda Fink.

This recording is bound to be reissued

where it will find new competition from

Opera Raraís live performance recorded

at the Edinburgh Festival in 2004 (ORC

27) and with Antonio Siragusa managing

the vocal leaps of the David role of

Ilo with ease and welcome tonal beauty.

The down-side is the increasing intrusion

of vociferous applause as the performance

proceeds. The issue includes additional

material Rossini composed for Vienna.

On the way to Vienna Rossini and Colbran

were married. Under the arrangement

Rossini received a dowry equivalent

to about £100,000 at todayís values.

With this money, together with his fees

for the Vienna performances, Rossini

was beginning to have the financial

security he sought and which would relieve

him of the pressures of the hectic compositional

life he had, of necessity, lead previously.

Barbaja, increasingly aware of Rossiniís

asset value was keen to negotiate a

new contract to keep the composer attached

and committed to Naples whilst allowing

him to compose for London and Paris.

Rossini, on the other hand was determined

not to return to Naples and whilst in

Vienna he wrote to the London impresario

Benelli proposing a new opera for that

city involving his wife as lead soprano.

Whilst in Vienna, Rossini was introduced

to Beethoven. The great Austrian composer

encouraged Rossini to write more comic

operas like Il Barbiere di Siviglia.

Rossini for his part was appalled by

Beethovenís living conditions and financial

situation.

The Rossinis left Vienna in July 1822.

It was a measure of Rossiniís status

that he was invited by Prince Metternich

to attend and compose for the Congress

of Verona. During several weeksí stay

he composed five cantatas as well as

attending many receptions. He was introduced

to the Austrian Emperor, the Tsar and

the Duke of Wellington. From Verona

the Rossiniís journeyed to Venice where

the composer had agreed to write an

opera for La Fenice. His fee was an

unprecedented five thousand francs.

During this stay Rossini also presented

the revised version on Maometto II

referred to above.

The new opera for La Fenice was Semiramide

(No. 34) based on Voltaireís tragedy.

The work was well received at its premiere

on February 3rd 1823. It

was performed twenty three times that

season and quickly spread throughout

Italy, Europe and, later, America. After

some years of neglect Semiramide

was revived at La Scala with Joan

Sutherland in the title role. These

performances were the stimulus for Deccaís

recording, which also features Marilyn

Horne in the trousers role of Arsace.

(425 481-2). A new critical edition

was staged at Pesaro in 1992 and is

used in the complete DG recording of

the same year featuring Cheryl Studer

in the name part, Jennifer Larmore,

Samuel Ramey and Frank Lopardo (437

797-2). In Semiramide Rossini

elaborated his stylistic vision. It

was the last opera he composed for the

Italian stage. At age 31 he was ready

for new horizons

After spending time in Bologna in the

summer of 1823 the Rossinis travelled

to London via Paris where the composer

was fêted and began negotiating

about future work. In London he presented

several of his operas although their

success was constrained by Colbranís

declining vocal state. Rossini did,

however, earn considerable remuneration

by singing and playing at musical occasions

organised by English aristocracy. In

Brighton where the Court was in session

he sang duets with the King. The proposed

London opera, although started, was

never completed when Benelli went bankrupt.

The Rossinis returned to Paris, where

the composer was appointed Director

of the Théâtre Italien.

His contract required him to present

productions of his own works, and that

of other composers, as well as writing

new works in French for presentation

at The Opéra (The Théâtre

de líAcadémie Royale de Musique).

The works in French were a little slow

in coming, as Rossini needed to grapple

with the prosody of the language and

re-align his own compositional style

towards that of his new hosts. All this

was to take time and whilst there was

some impatience at the lack of a new

opera from him in French it was recognised

that his revitalisation of the Théâtre

Italien was demanding of his time. First

though was the unavoidable duty of a

work to celebrate the coronation of

Charles X in Reims Cathedral in June

1825. Called Il viaggio à

Reims (a journey to Reims) (No.

35) it was composed to an Italianís

libretto and presented at the Théâtre

Italien on 19th June. It

was hugely successful in three sold-out

performances after which Rossini withdrew

it considering it purely a pièce

díoccasion. The opera plot makes a parody

of the stereotypes of the various nationalities

who become stranded, through lack of

horses, on the way to the Coronation

of Carlos X in Reims. Although Rossini

reused nine of the numbers in Le

Comte Ory (No. 38 below), Il

viaggio became lost until scholarly

research work found missing numbers

in the Santa Cecilia in Rome. By adding

these parts to those found in Paris

and Vienna, Philip Gossett produced

the edition presented at the Pesaro

Festival in 1984. DG engineers combined

the best of the Pesaro performances

to give an outstandingly sung and recorded

issue (414 498-2). That should be a

part of any collection of Rossiniís

operas. There is also available a DVD

of a performance at Barcelonaís Grand

Liceu in March 2003 conducted by Jesus

Lopez-Cobos (TDK DV-OPVAR)

For his first work in French, Rossini

established a tradition later followed

by Donizetti and Verdi of revising an

earlier work to a new libretto. The

first of two such revisions was Le

Siège de Corinthe (No.

36). It was premiered to massive acclaim

at The Opéra on October 9th

1826. This was Rossiniís second revision

of Maometto II. Whilst the first

revision, as noted, reduced the length

of the work, for the Paris performances

Rossini added an overture, several new

numbers and the de rigueur ballet. It

clocked up no fewer than one hundred

performances at The Opéra within

thirteen years. It was quickly seen

in translation throughout the Italian

peninsula as LíAssedio di Corinto.

The Paris staging was lavish with the

final tableau depicting the sacked and

burning Corinth being both viscerally

and visually thrilling and horrifying.

Francis Toye wrote Ďwith this work Grand

Opera was borní. The plot concerning

Greeks and Turks was particularly apposite

in the Paris of the premiere where the

Greek cause found much favour. It needs

another spectacular staging to be caught

on DVD to bring this French version

back into favour. As it is, there is

a worthwhile studio recording conducted

by Thomas Schippers of the Italian translation

in a version prepared for La Scala in

1969 featuring Beverly Sills and Shirley

Verrett (EMI CMS 64335-2).

Rossiniís second work for The Opéra

was Moïse et Pharaon (No.

37). Derived from the Italian Mosé

in Egitto, the revised French language

libretto involved several name changes

and expanded the opera into four acts.

The necessary ballet music in act 3

was taken from Armida. As well

as new music Rossini also drew from

Bianca e Faliero. Moïse

et Pharaon was premiered on

6th March 1827 and was received

with even greater appreciation than

that accorded Le Siège de

Corinthe. An Italian translation

called Mosé e faraone quickly

followed. The newly issued DVD of the

2003 La Scala production conducted by

Muti ( to be reviewed) fills a major

gap in the availability of Rossiniís

works. Although lacking Francophone

singers, and having some idiosyncratic

stage effects, the recording provides

a vivid and well-sung performance of

a work that deserves greater circulation.

A month before the premier of Moïse

et Pharaon, Rossiniís mother died

in Bologna. The composer took her death

badly and after bringing his father

to Paris he increasingly talked of retirement.

By the spring of 1828 the Paris newspapers

were speculating about a possible end

to his career as an opera composer.

In this period he wrote some occasional

music and despite having agreed to write

Guillaume Tell for The Opéra

he first turned his hand to a comic

work, Le Comte Ory (No.

38). For this opera he re-used five

of the nine pieces in Il viaggio

a Reims, and reduced the need for

primo voices. First heard on 20th

August 1838 Le Comte Ory further

consolidated Rossiniís reputation. It

was a favourite work of Vittorio Gui,

music director of the Glyndebourne Festival,

and a recording was made after performances

at the Edinburgh Festival in 1954. This

scintillating performance kept the work

in the public domain and the LP catalogue,

along with Il Barbiere and La

Cenerentola, until the composerís

other works  began

to be more widely performed and recorded

from the mid-1970s. In sonic terms it

has largely been superseded by Philipsí

highly enjoyable 1988 recording conducted

by John Eliot Gardiner deriving from

performances at the Lyons Opera (review).

A more recent audio recording from the

Pesaro Festival

began

to be more widely performed and recorded

from the mid-1970s. In sonic terms it

has largely been superseded by Philipsí

highly enjoyable 1988 recording conducted

by John Eliot Gardiner deriving from

performances at the Lyons Opera (review).

A more recent audio recording from the

Pesaro Festival  features

Juan Diego Florez. His pinging top notes

and ease in the highest register are

not enough for my ears to overcome the

disadvantages of a live audio performance

and an uneven cast (DG 477 5020). More

welcome has been the arrival of a DVD

of the 1997 Glyndebourne production.

It is a wholly delightful performance

well caught for the medium by nonpareil

video director Brian Large (review).

features

Juan Diego Florez. His pinging top notes

and ease in the highest register are

not enough for my ears to overcome the

disadvantages of a live audio performance

and an uneven cast (DG 477 5020). More

welcome has been the arrival of a DVD

of the 1997 Glyndebourne production.

It is a wholly delightful performance

well caught for the medium by nonpareil

video director Brian Large (review).

In 1828 when Rossini began composing

Guillaume Tell

(No. 39) he was 36 years old and following

the death of Beethoven he was the worldís

best-known composer. It was to be his

last opera despite his living until

his 76th year. As Director

of Parisís Théâtre Italien,

Rossini had a guaranteed annuity for

life and had earned considerable sums

at the 1822 Vienna Festival and during

his visit to London. With good counsel

from banker friends he had enough money

to live in style. Many have speculated

that given his liking for social activities

he saw no reason to continue the strained

and hectic life he had perforce been

leading. There was also the question

of his mental resilience and physical

state. His marriage was not successful

and he was much distressed by his motherís

death. His physical state was affected

by his chronic gonorrhoea exacerbated

by frequent, and futile, stringent treatments

and which certainly lead to depression.

Whilst Rossini had hinted at possible

retirement during the composition of

Guillaume Tell, the work

itself shows no signs of any waning

of musical creativity, or capacity and

concern for detail on his part. It is

by far his longest opera, a complete

performance lasting nearly four hours.

Rossini took excessive care over its

libretto, casting and composition. Sections

at the end of act 2 where the representatives

of the three Cantons assemble and agree

to revolt against the tyranny of Governor

Gesler draw from Rossini some of his

most memorable music in an opera full

of melodic and dramatic felicity. Donizetti

is reputed to have attributed the rest

of Guillaume Tell to Rossini

but act 2 to God!

Because of its length there was an

early propensity to cut out sections

of Guillaume Tell. Within

a year it was presented in three abbreviated

acts and then act 2 only was given as

a curtain-raiser to ballet performances!

The opera was first presented in Italian

translation at Lucca in 1831 and then

at the San Carlo in Naples in 1833.

Commendable audio recordings are available

in both the original French and Italian

translation. The French has Nicolai

Gedda and Caballé under Gardelliís

baton (CMS 769961-2) whilst  the

Italian version has Pavarotti and Mirella

Freni conducted by Chailly (Decca 417

154-2). Both recordings, on four CDs,

feature a full text and tenors with

good upward extensions well able to

assay the 456 Gs, 93 A flats, 54 B flats,

15 Bs, 19Cs and 2 C sharps required

of the role of Arnold. There is also

a DVD of the 1988 La Scala performance

available (Opus Arte OA LS 3002 D) [review].

The reviewed CD from Orfeo (review),

is of a live performance in French given

at the Vienna State Opera in 1998. Giuseppe

Sabbatiniís tightly focused, but ever

musical and tastefully phrased tenor

meets the demands of the high notes

if not

the

Italian version has Pavarotti and Mirella

Freni conducted by Chailly (Decca 417

154-2). Both recordings, on four CDs,

feature a full text and tenors with

good upward extensions well able to

assay the 456 Gs, 93 A flats, 54 B flats,

15 Bs, 19Cs and 2 C sharps required

of the role of Arnold. There is also

a DVD of the 1988 La Scala performance

available (Opus Arte OA LS 3002 D) [review].

The reviewed CD from Orfeo (review),

is of a live performance in French given

at the Vienna State Opera in 1998. Giuseppe

Sabbatiniís tightly focused, but ever

musical and tastefully phrased tenor

meets the demands of the high notes

if not  quite

having the heft and robust tone the

role ideally requires in its most dramatic

moments. Nancy Gustafson as Mathilde

is less than ideal whilst Thomas Hampson

in the title role sings well and Fabio

Luisi is the outstanding conductor.

All round it is a vibrant performance

but misses around 40 minutes of music

compared with the studio recordings

mentioned. Davis Pountneyís production

was not appreciated by many of the audience

who voice their disapproval from time

to time.

quite

having the heft and robust tone the

role ideally requires in its most dramatic

moments. Nancy Gustafson as Mathilde

is less than ideal whilst Thomas Hampson

in the title role sings well and Fabio

Luisi is the outstanding conductor.

All round it is a vibrant performance

but misses around 40 minutes of music

compared with the studio recordings

mentioned. Davis Pountneyís production

was not appreciated by many of the audience

who voice their disapproval from time

to time.

No collection of Rossiniís operatic

works would be complete without a collection

of overtures from his

operas, all of them full of melodic

musical invention and unexpected felicities.

Ola Rudnerís ABC Classics CD

(review) has nine whilst a Double Decca

from Chailly manages fourteen (443 850-2).

A Philips Duo CD issue of Rossiniís

ballet music from Le Siège

de Corinthe, Otello, Moïse

and Guillaume Tell, along

with some of Donizettiís ballet music

composed for his Paris works and conducted

by Antonio De Almeida is worth hearing

(442 533-2).

Also essential are vocal recitals from

some of the leading Rossini singers.

The dramatic  low

mezzo Ewa Podles features six arias

recorded live at a concert in her native

Poland in 1998 (DUX 0124) [review].

She also sings arias from

seven of his operas including Semiramide,

Maometto II and La donna del

lago in a highly enjoyable 1995

studio recording (Naxos 8.553543). Also

commendable is fellow mezzo and great

exponent of Rossini, Marilyn Horne.

She can be heard on an excellent Decca

recording titled Heroes and

low

mezzo Ewa Podles features six arias

recorded live at a concert in her native

Poland in 1998 (DUX 0124) [review].

She also sings arias from

seven of his operas including Semiramide,

Maometto II and La donna del

lago in a highly enjoyable 1995

studio recording (Naxos 8.553543). Also

commendable is fellow mezzo and great

exponent of Rossini, Marilyn Horne.

She can be heard on an excellent Decca

recording titled Heroes and  Heroines

(476 7089) and which features arias

from six operas including extensive

excerpts from the rarely heard Líassedio

di Corinto. She also features on

a CD of alternative arias that Rossini

wrote for specific singers and productions

after the premiere [review].

Heroines

(476 7089) and which features arias

from six operas including extensive

excerpts from the rarely heard Líassedio

di Corinto. She also features on

a CD of alternative arias that Rossini

wrote for specific singers and productions

after the premiere [review].

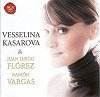

The recent tenore di grazia favourite,

Juan Diego Florez, sings in some duets

with Vesselina Kasarova on her all-Rossini

CD (RCA 74321 57131 2)  that

made the charts in 1999 as did his 2002

solo disc of tenor arias from eight

of the composerís works (Decca 470 024

-2). The three Rossini items involving

Kasarova and Florez from the RCA issue

are repeated on a recommendable disc

of duets constructed round the Bulgarian

mezzoís previous recordings. (RCA 82876

52929 2) [review].

On the remaining tracks she is joined

by Eva Mei and Ramon Vargas in excerpts

from the 1995 recording of Tancredi

(RCA 09026 68349 2) whilst the duet

from Maometto II comes from an RCA disc

called Between Friends and focuses on

Vargas (RCA 82876 54243 2) (review)

Samuel Ramey, with his flexible sonorous

bass was a great favourite at Pesaro,

and on disc, in a number of Rossini

roles. His recital disc on Teldec is

well worth searching out (9031-73242-2).

that

made the charts in 1999 as did his 2002

solo disc of tenor arias from eight

of the composerís works (Decca 470 024

-2). The three Rossini items involving

Kasarova and Florez from the RCA issue

are repeated on a recommendable disc

of duets constructed round the Bulgarian

mezzoís previous recordings. (RCA 82876

52929 2) [review].

On the remaining tracks she is joined

by Eva Mei and Ramon Vargas in excerpts

from the 1995 recording of Tancredi

(RCA 09026 68349 2) whilst the duet

from Maometto II comes from an RCA disc

called Between Friends and focuses on

Vargas (RCA 82876 54243 2) (review)

Samuel Ramey, with his flexible sonorous

bass was a great favourite at Pesaro,

and on disc, in a number of Rossini

roles. His recital disc on Teldec is

well worth searching out (9031-73242-2).

In preparing this conspectus I have

been indebted to the following sources:-

- Gioachino Rossini. Philip

Gossett in The New Grove, Masters

of Italian Opera, pp 1-90. Edited

Stanley Sadie. Macmillan, London,

1983

- Rossini. Charles Osborne.

Master Musicians Series. J M Dent.

1987

- The Bel Canto Operas. Charles

Osborne. Methuen 1994. pp 3-136 and

Selective Discography pp 356-359

- Innumerable CD booklets and sleeve-notes,

often by Philip Gossett who, for the

last thirty years or so, has been

widely accepted as the foremost Rossini

scholar. He, together with Alberto

Zedda, conductor and fellow scholar,

did much to establish the Rossini

Foundation and Festival at Pesaro.

Robert J Farr

16 November 2005