The fifteen Mystery

Sonatas date from approximately 1674

and are works of the utmost spirituality.

Biber wrote them - he was himself a

virtuoso violinist and a technical innovator

not least in his use of scordatura,

a retuning of the violin

from the standard fifths - as

representative of moments in the lives

of Christ and the Virgin Mary. They

are pictorial and not obviously representational.

The Mysteries are presented sequentially

– the five Joyful mysteries followed

by the five Sorrowful Mysteries and

finally the five Glorious Mysteries

– and ending, properly speaking, with

the great unaccompanied Passacaglia

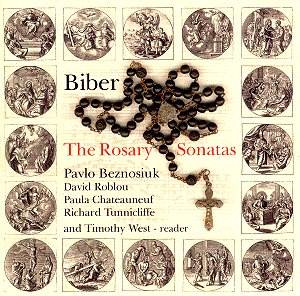

(as here). In the extraordinary manuscript

of the Sonatas, housed in the Bavarian

State Library, there are fifteen engravings

(probably taken from a Rosary Psalter)

depicting the fifteen mysteries whilst

the concluding Passacaglia has an engraving

of a Guardian Angel holding a child’s

hand. In this recording Timothy West

prefaces each sonata as he reads from

3 Rosary Psalters.

Pavlo Beznosiuk has

been associated with Biber’s Rosary

Sonatas for a number of years now and

his performances are invariably eagerly

anticipated. Surrounding him is an experienced

accompanying group, like-minded and

expressive, creating textures of great

depth with theorbo, archlute, viola

da gamba and violone as well as harpsichord

and chamber organ. Beznosiuk evokes

the tension and ascending lines, full

of the purest expectation, in the Annunciation

and finds grandeur and nobility in the

Allemanda of the second sonata, the

Visitation. Equally open to the expressive

tenderness and delicacy of the Nativity

(an especially well voiced Courante/Double)

he impressed me especially strongly

in the swaying and crispness and colourful

attacca style, full of edge, in the

Ciacona of The Presentation in The Temple.

The aptness of that instrumental group,

for example, can be exemplified by the

archlute in the Sixth Sonata. Beznosiuk

is fine at the communing intimacies

that course through the Sonatas (the

first Adagio of the Sixth, say) or in

the acrobatic leaps of the Ninth or

the same sonata’s tentative frailty

and final, abrupt ending.

The searing Crucifixion

is followed by a Resurrection conjoined

with drone and imitative writing, coupled

with spare, elliptical drama and an

emergent Hodie Hymnal of devastating

candour. But Biber manages to vest these

sonatas with rustic brio as well (see

the Intrada of No.12) as much as the

increasing exultation of the Descent

of the Holy Ghost and the Assumption,

ending in the noble lyricism (well played

by Beznosiuk) of the Sarabanda of the

Fifteenth. The great Passacaglia tends

to heighten a perception that only once

or twice had impinged, namely that Beznosiuk

sees the ebb and flow of its rhetoric

as intensely human and as a result susceptible

of some metrical daring. He doesn’t

take it as an unwavering Passacaglia

arch, tending rather to coil and uncoil

with fervour, if sometimes threatening

the structure. A modern instrument performance,

such as that by the Czech violinist

Gabriela Demeterova takes an opposite

view – and it’s one I share, but there’s

no denying Beznosiuk’s understanding.

There are plenty of

competitors in the repertoire, from

such as Demeterova (Supraphon) and original

instrument performances from such well-known

musicians as Holloway and Moroney, and

Reiter and the group Concordia. But

Avie’s release is very attractively

produced in a resonant acoustic, with

fine notes – and makes for enjoyably

spiritual listening.

Jonathan Woolf