When one looks into

somewhat older books on the life and

works of Antonio Vivaldi, there is little

chance that the vocal works are discussed.

And if they are discussed it is the

sacred works for soloists, chorus and

orchestra that get attention. The motets

are mostly completely ignored.

Twelve motets are extant,

two of which are incomplete. But there

is conclusive evidence that Vivaldi

composed a fairly large number of motets.

The genre of the motet was very popular

in those days and Vivaldi was not going

to be an exception. In the liner notes

Angelo Chiarle writes: "In eighteenth-century

Italy, a 'motet' was understood as meaning

a vocal work that was sacred but non-liturgical

in character, to a text in Latin verse.

Its place was in the moments of relative

silence during Mass (Offertory, Elevation

and Benediction) or Vespers (between

two psalms, given that the antiphons

were by that period rarely set to music)."

The practice of performing motets like

those of Vivaldi and his contemporaries

during Mass wasn't generally accepted:

the ecclesiastical authorities tried

to limit such performances. One of the

reasons was the character of the lyrics,

which according to the French author

Pierre-Jean Grosley (1764) were "a sorry

collection of rhymed Latin words, in

which barbarisms and solecisms are commoner

than good sense and reason."

In fact, motets were

first and foremost showpieces for singers,

often written for specific singers.

Many of Vivaldi's motets were written

for his pupil, later assistant Anna

Girò, who was a mezzo-soprano.

The structure is standardised:

every motet contains two arias, interspersed

by a recitative, and closes with an

'alleluia'. The scoring is solo voice

- either soprano or mezzo-soprano/contralto

- with strings and basso continuo.

Some of the motets

were written for the Ospedale della

Pietà in Venice, where Vivaldi

worked a large part of his life. But

others were written to be performed

in Rome, which Vivaldi visited in 1723

and 1724 and where he was in close contact

with Cardinal Ottoboni.

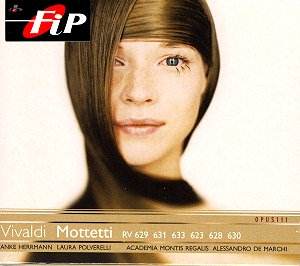

The present recording

is part of a Vivaldi Edition which aims

to record all extant compositions of

Antonio Vivaldi. A large part of the

job will be done by Italian soloists

and ensembles.

There is every reason

to be happy with the contribution of

the Academia Montis Regalis here. The

playing is very colourful and follows

the text of the motets very closely.

That makes it especially disappointing

that I can't recommend this recording

without reservation because of the inconsistent

performances of the singers.

Let me start with saying

that there are some excellent moments.

The last item on this disc, and one

of the most famous of all Vivaldi's

motets, 'Nulla in mundo pax sincera',

is sung very well by Anke Herrmann.

The contrasting character of the two

arias comes across convincingly, and

Ms Herrmann has no problems in this

technically demanding piece. She also

illustrates the singing of the nightingale

in the opening aria of 'Canta in prato'

very nicely.

Laura Polverelli does

quite well in 'Invicti, bellate', clearly

distinguishing between the two arias,

of which the first has a 'battaglia'

character, whereas the second is much

softer, being a prayer to Jesus that

the enemy - the night - may be beaten.

Unfortunately there

are also serious flaws in their singing.

The fact that I don't particularly like

their voices is a matter of taste. Their

extensive use of a rather wide vibrato

isn't: in the 18th century vibrato was

an ornament, not a way of singing, as

is the case here. A clear articulation

of the text isn't one of the strengths

of the singers anyway, and the extensive

use of vibrato doesn't make it any easier

to understand the lyrics.

Sometimes the voice

of Anke Herrmann does sound stressed

and uncomfortable, in particular in

the upper register, for example in the

opening aria of 'O qui caeli terraeque

serenitas'. The ornaments don't seem

to come very natural and the performance

lacks variety.

The two arias of 'Vestro

Principi divino' are characterised in

the booklet as "joyful and nimble",

but Laura Polverelli's interpretation

is rather dour and not joyful at all.

The dark colour of her voice doesn't

help in this respect.

These motets may be

vocal showpieces, but in my view the

abundance of ornamentation in the da

capo of the first aria of 'Longe mala,

umbrae terrores' seems somewhat over

the top. It doesn't enhance the expression,

but rather weakens it.

It is a shame that

the opportunity has been missed to deliver

a recording which does these motets

full justice.

Johan van Veen