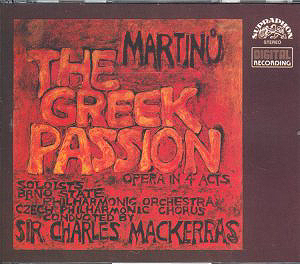

During

the mid-1950s Martinů was looking for a suitable Czech subject

for an opera. He was knocked off course by discovering the Kazantzakis

novel ‘Zorba the Greek’. He even toyed with setting Zorba but

eventually found it an intractable challenge. He turned instead

to the same author's ‘Christ Recrucified’ but changed the title

to ‘The Greek Passion’. It is Martinů's last but one opera,

the final one being Ariane (also recorded on Supraphon).

In

1957 he completed it ready for Kubelik to produce at Covent Garden

however the Garden authorities rejected the work. Martinů

went back to the drawing board and produced a transformed new

version directing it to the Zurich Festival. The first version's

materials were lost until a reconstruction was made ready for

the Bregenz Festival in 1999. This was prepared by Aleš Březina.

The Bregenz performance was recorded on Koch conducted by Ulf

Schirmer. The Supraphon recording uses the revised version - the

one premiered by Paul Sacher on 9 June 1961 two years after the

composer's death. It took until 29 April 1981 for The Greek

Passion to be premiered in the UK at the New Theatre Cardiff,

Welsh National Opera under Charles Mackerras.

The

plot. The setting is the Greek village of Lykovrissi. The time

- early 20th century. A passion play is being prepared. Manolios

is to play Christ. When some refugees arrive the priest tells

then to leave. Manolios suggests where they might stay outside

the village. Katerina is obsessed with Manolios. Manolios rejects

physical passion with Katerina who plays Magdalene and she accepts

spiritual love. Manolios becomes increasingly Christlike. At a

village wedding the priest excommunicates Manolios. Panait, who

plays Judas, kills Manolios outraged at his assumption of the

role of Christ. There is mourning for the death and the refugees

prepare to leave. The opera amplifies and distorts the usual interplay

of love, guilt, envy and anger.

There

are various spoken sections including in Act 3 the conversation

between Grigoris, Patriarcheas and Ladas in which they condemn

Manolios for his Christlike exhortations about sharing property

and also in Act 2 Sc.1 when Ladas reveals his plans to exploit

the desperate refugees.

This

is a very different work from the opera Julietta. The floatingly

surreal is replaced with a dramatically cogent sense of direction

at both musical and narrative levels. Julietta can seem

perplexingly poetic. The Greek Passion pushes forward all

the time. Tragedy jostles with poetry. It helps that the libretto

is in English.

The

work bursts onto the scene like the start of La Bohème.

After a reverential hymn the music delivers a buzzing tension,

an exciting jangle of bells (a recurrent presence in this opera)

and a hum of expectation. The choral contributions throughout

have the colossal quality of Mussorgsky's crowd scenes. This applies

to both the villagers' choir and the crowd of refugees. The orchestral

tissue is rich and seething with Martinů hallmarks. In addition

there are new touches like the guitar (bouzouki?) effects at 11.02

and 19 53 in Act 1. In the second act's first bars the orchestral

evocation of a mystical dawn is touched with the exoticism of

Szymanowski's King Roger. Folk influences are felt in both

the concertina and Nikolios’s pipe playing on Mount Panagia. In

Act 3 Grigoris, driven by hate, speaks his threats over drumbeats.

In Act 4 there is the chatter and wheeze of the village band.

The chanted word: ‘amin amin amin’ recalls the imploring calls

of the choir in Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass. When Grigoris

formally excommunicates Manolios, Michelis, Yannakos and Kostandis

all stand with Manolios and the orchestra announces the joy of

their fidelity to the ideal. This is Martinů’s closest approach

to grand opera with tragic and spiritual dimension.

It

is regrettable that Supraphon chose to have only a single band

for each act. A full libretto is provided with sung English and

parallel translations into German, French and Czech. There are

no separate notes about the opera and its writing.

Rob

Barnett