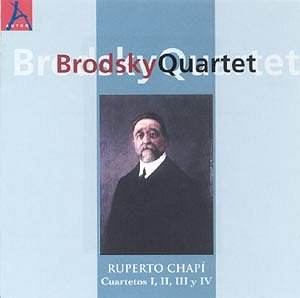

Ruperto

Chapí was the chameleon of 19th century Spanish music.

Best known for his highly popular zarzuelas, operas and orchestral

suites such as the Fantasía morisca and Los gnomos

de la Alhambra, his greatest gift was to synthesise diverse

influences and styles into attractive pieces more remarkable for

energy and compositional skill than for individuality. Maybe we're

too prone to praise innovators, leaders rather than consolidators

of fashion. Certainly few composers wear borrowed clothes with

Chapí's ingenuity or aplomb. Then again, intelligence,

wit and imagination are rare enough commodities; and whatever

his limitations, the composer of great zarzuelas of the quality

of La revoltosa or La bruja had enough of those

and to spare.

The

reputation of these String Quartets, written late in Chapí's

career, has intrigued those of us who know him almost exclusively

through his zarzuelas. By 1903, when No.1 was written for the

Cuarteto Francés, much of his best stage work was behind

him; but judging from contemporary reaction - as reported both

in Luis G. Iberni's sleeve-note here, and his authoritative study

of Chapí's life and work - the Quartets excited and divided

critical opinion to an unexpected degree.

Thanks

to the Brodsky Quartet we finally have the chance to find out

what it was that made madrileño music lovers a century

ago sit up and take notice. Chapí's foray into a genre

which, since the time of Haydn, has been the chosen vessel for

the deepest thoughts of so many great and not-so-great composers

must have come as a surprise. Even so, in their consciously Beethovenian

ambition, their virtuosity and unpredictable alternation of sun

and shade, they do come as something of a revelation.

Chapí

was not of course the first stage composer to try his hand at

a String Quartet. In No.1, Verdi's sole example comes to mind

by reason of Chapí's comparably assured technique and focus.

Like the Italian, he is content to take the expressive possibilities

of the form as he finds them, but arresting gestures, good tunes

and theatrical contrasts keep us highly entertained throughout

the work, which culminates in an energised Finale combining zortzico

and jota rhythms. The whole may not equal the sum of the

parts, but this is living music, mainstream European in language

but - unlike his rival Tomás Bretón's more sombrely

classical chamber pieces - recognisably Spanish in accent.

Its

successors share No.1's four-movement structure as well as its

boldness and fire. No.2, written for the Czech Quartet - Josef

Suk on second violin and Oscar Nedbal on viola - is more nationalist

in tone. It begins with some delicate alhambrismo, Aida

embracing Thaïs in a poetic Andalusian nocturne. The later

movements, with their unpredictable tonal shifts, are equally

attractive, witty and elusive, even if the pizzicato ostinato

of the third movement is a little too obvious an exercise in Beethovenian

bizarrerie.

The

brooding first movement of the more classically compact No.3 is

Franckian in feeling, whilst the epicurean melancholy of the Larghetto

recalls early Debussy - though the pulsing Allegro finale,

thematically integrated with the earlier movements, is much more

Mediterranean in temper. The harmonic simplicity of No.4 initially

strikes a contrasted pose, Dvořákian in melodic cut, easy

amplitude and harmonic procedures. Its urbane Allegretto

is interrupted by a surprisingly morose, world-weary lento,

stamping a more personal dimension on a work otherwise richer

in romantic suavity than depth of feeling.

It

would be folly to pretend that the rediscovery of Chapí's

Four rewrites the established order of the String Quartet. Intelligently

varied, well stocked with musical and technical interest, their

very diversity works against a compelling sense of emotional through-line

- at this level underlying personality does count, and they owe

much to Beethoven and his successors. Again, they are ambitiously

structured, and despite Chapí's easy formal grasp some

movements are thematically lightweight enough to feel overlong.

No matter. This is music which gives a deal of pleasure, plenty

of food for thought, music which is always alive, music for which

it is impossible not to feel growing affection, even love.

The

Brodsky Quartet convey the spirit of these underrated works superlatively

well. Their virtuosity is impressive, and technical challenges

are generally well met. Their alertness and sensitivity to Chapí's

quicksilver moods is unfailing, and they convey a freshness which

adds greatly to the pleasure of this rediscovery. The clear, unfussy

recording is another plus.

Which

makes it all the more stupid that nobody - neither the production

company Autor, nor the Quartet's own online sales outlet - seems

to care enough about this important issue to offer any distribution

outside Spain, even in the Brodskys' native UK. After a century

of undeserved neglect, Chapí's String Quartets - and the

Brodskys themselves - deserve a better deal.

Christopher

Webber