This Third Symphony is a cracker.

I immediately recommend you buy this disc.

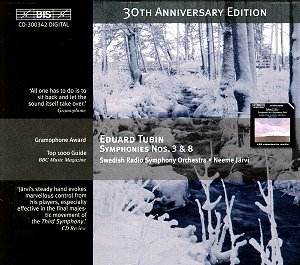

It is almost exclusively to the conductor Neeme

Järvi that we owe a real debt of gratitude for making known

the works of Eduard Tubin since he introduced them to the West

while he was living in the USA.

Tubin was born in 1905 in Estonia close to the

border with Russia. Eduard inherited a lot of music from his brother

who died young. His father played the trumpet in a village band

and was a tailor by trade and enjoyed fishing. In his duties looking

after the pigs young Eduard played the flute. Who says a composer's

life is a glamorous one? His father sold a calf to enable his

son to have music lessons and he also learned to play the balalaika.

When Eduard was still young, Estonia declared its independence

and was attacked by Russian communists and the Germany army. Eduard

studied at Tartu and became a teacher and conducted the College

choir. He gave the first performances in Estonia of Debussy's

La demoiselle élue and Stravinsky's evergreen Symphonies

of Wind Instruments.

While in Budapest he showed his first two symphonies

to Zoltan Kodaly who was a great encouragement. I have never understood

why the congenial William Walton did not like Kodaly! I believe

it was Kodaly's unassuming influence that led Tubin to visit Estonian

islands to collect folk songs.

His beloved Estonia was invaded in 1940 by Soviet

troops. Tubin was head of composition at Tartu at the time. He

was sent reluctantly to Leningrad to study Soviet music and culture.

Eventually he was exiled in Stockholm where he directed a male

voice choir.

Neeme Järvi emigrated from Sweden to the

USA in 1980 and programmed works by fellow Estonians including

Tubin.

The Symphony no. 8 of 1966 is an introspective

work in four movements written in the twentieth year of his exile

in Stockholm. It is a sinister work sometimes sparse like the

desolate Finnish landscapes that Sibelius realised so effectively.

The music often has a chamber orchestra feel about it. The opening

andante quasi adagio is deeply felt and sounds to me like a very

sober lament rising and falling in various degrees of tension.

But there is always a menacing undercurrent and an unbearable

tragedy. It is not comfortable music. Perhaps it is nostalgic

longing for his own country. Some of the melodic fragments suggest

folk songs. The orchestration is remarkably clear and expertly

textured. Beautiful if a little strange! The second movement is

marked allegro moderato often curiously subdued again and marked

by economy but not miserliness. Some outbursts occur which heighten

the tension and the movement is clearly held together by recurring

wisps of melody. The movement ends with an alarm. There follows

an allegro vivace but it is not that vivace. It seems to be a

protest movement and it builds up to a great climax with cymbals,

tam-tam and braying horns and energetic strings. The protest is

a procession which: is coming, is there and disappears into the

distance! The coda is sinister and decidedly creepy!

The finale is slow marked lento, tenuto e maestoso.

The brass chorale is uncanny and uncomfortable as is the rest

of the movement. Don't be put off by the word lento. The music

does not grind but it does not always flow either. There is some

eventual drama which is very impressive with a long high soaring

and beautiful violin line and crashing tam-tam!

This is clearly a very personal symphony and

, while I do not like comparisons, I think I could safely compare

this with Sibelius's Symphony no. 4 in A. You either love it or

hate it. But with Tubin's Eighth there is an extraordinary chilling

beauty!

The Symphony no. 3 began in 1940 when Estonia

was occupied by the Soviet army. The opening largo has a march

like style and a glorious soaring violin line supported by horns.

The march develops into a very impressive procession. I am sure

Robert Farnon, had this, or something like this in mind, when

he wrote the Colditz March. This largo leads into a rugged fugue

or fugato but, as with Shostakovich, it seems to portray the war

machine, the invaders. The orchestral punctuation is quite staggering

and the Swedish orchestra is very fine and I need not comment

about its conductor. At 5.20 there is a soulful tune reminiscent

perhaps of the folk songs of Hiiumaa. The energico section is

full of high drama with bold rugged music with crashing tamtam

and a vital drive, superbly orchestrated. Shrill flutes, vigorous

strings and sinister percussion all add to the excitement and

it is real excitement. Sometimes the music sounds like a mighty

cathedral organ at full throttle!

Despite the highly scored orchestration all is

clear in this amazing performance. Be warned, hold on to your

hats for the final minute. You will want to jump up and applaud.

It is that good!

The second movement is quick, too. It is headed

molto allegro e temptestoso. Here Järvi exercises great control

in an agitated piece full of nervous and uneasy energy. The tension

becomes too much. We know we are heading for an explosion. We

are fooled once when we think it is about to happen but when it

does it is simply terrifyingly marvellous! The moments of calm

are necessary. There is a violin solo of some pathos, played by

Bernt Lysell, who just avoids being sugary, a lone voice, a voice

in the wilderness lamenting the despicable acts of the Soviets

but who will listen? Who cares but Estonians? This is lovely music,

so human and so real. The agitation returns and approaches with

menace hiding periodically and then re-emerging and with the vicious

tread of despots. The end is a surprise more akin to Mendlessohn's

A Midsummer Night's Dream than anything else.

Largo, maestoso is the heading for the finale

but this is not a slow quiet tedious piece. Often it hits you

between the eyes. Curiously there is a warmth. After the premiere

in Tallinn on 26 February 1943 the conductor Olav Roots spoke

of "the music's despair, obstinacy and hatred which overcame

a race who wanted to regain its lost independence." This finale

highlights confidence and the strength of the Estonia people.

No wonder the Estonian public gave it a prolonged and standing

ovation. There seem to be several marches playing all at once

and a nobilmente devoid of pompous arrogance! The ending is both

colossal and exciting!

The sound engineers have done a great job!

This is a memorable disc.

David Wright