To

say of a work such as Carmina Burana that a particular

recording is the very best ever made is something of a presumption,

considering there are hundreds of recordings, and surely reasonable,

knowledgeable, discriminating persons would diverge in their preference.

In my more rational moments, I have been known to admit there

are many good CBs, Ormandy, Previn, Shaw, for instance.

But, sorry, I guess right now Iím not being very rational and

there is only one best of the best: Eugen Jochum 1953 on monophonic

DGG.

Perhaps

I am prejudiced since I discovered this recording at the same

time I discovered hi-fi, in my early years of college when so

many vast intellectual horizons were opening up for me, great

music being just one of them. But since then I have noticed there

is a magic to first recordings. Nobodyís done it before. Nobodyís

told anybody how it should be done, so everything has to be worked

out and everybodyís a little scared that it might not come off.

Everybody knows they could have done many things, but chose to

do just this, just exactly this.

This

was hardly a first performance however, and the composer

was on hand. Certainly he must have been excited to know his music

was going to be preserved and the performers must have been especially

proud that he approved of their efforts. But there can hardly

have been any real bewilderment as to how the music should be

played, just some in how it should be recorded.

In

reviewing some great monophonic choral recordings one notices

that the most successful have a certain imprecision in the chorus.

You donít want a chorus so perfectly together that they sound

like one person. You want just enough diversification of the voices

so it sounds, over a single channel, like a group of people singing.

The Scherchen Bach Mass in b minor from 1952 is especially

successful in this way. Whether this was intentional or not, the

chorus sounds like a group of people who have something very important

they want to tell you, and later multi-channel recordings, however

excellent their ambiance and precision, may or may not have this

quality. With this group of Carminers, you can very well imagine

yourself going out to a tavern to get drunk and have a lot of

fun, all the more because youíre scared to death at what might

to happen tomorrow.

So,

strict critics will tell me, Iím excusing lapses in ensemble in

the chorus. What will I say about how the soprano can barely stretch

to the high notes? Will I find something good to say about that

too? Well, it isnít as bad as that, and she does sing extremely

well, with a certain innocence required by the part. Did Orff

even intend her to hit the high notes? He was there. He could

have thrown a tantrum and demanded they find someone else. Some

later sopranos who have no trouble with the high notes sound too

old, too professional for the text. Maybe Orff wrote the high

notes on purpose so they werenít hittable?

What

was for many years the crowning glory of this recording was the

Olim lacus colueram, the song of the roasted swan. My Jewish

friends angrily called it the song of the roasted Jew. At the

first performance of Carmina Burana at Hollywood Bowl (conducted

by Stokowski) some members of the audience got up in a body and

very noisily walked out. Those of us in the cheap seats didnít

hear much for a while. But most of the audience stayed. If anything

should rise above the horrors and hatreds of World War II music

should do it. Stokowski thought that, and I thought that. Carmina

Burana and I were both born in 1937, and I am as willing to

admit that the music is as innocent of genocide as I am innocent

in the firebombing of Dresden. Anyway, almost everybody stayed

at Hollywood Bowl and the performance continued. But I wondered

if any of this was the reason that Olim lacus colueram

was for many years by other artists performed way out of characteródeliberately

out of character? Simply sung off like a college glee? Thatís

all past now, too, and the melodramatic mock tragedy in this song

is now generally hammed up for all itís worth by famous tenors

and countertenors. But this first time through is still the best

ever done.

The

other crowning glory of this recording comes when the musical

circle comes full around and we begin the repeat of the opening

section with the shattering crash of full orchestra including

the tamtam. Very skilled and brilliant orchestras have played

this music, some of them much louder, but nobody, including Jochum

in his stereo remake, has ever captured the terror of this moment

so effectively. I think this may be a second where everybody in

the hall remembered that, a mere 8 years before, they were all

terrified, and truly wondered if there would be a tomorrow, if

the next crash would be the last sound they would ever hear, if

the circle would ever turn around again for them. Whatever the

magic, it was of that moment, and we have never heard it again.

But you can hear it now any time you want to.

This

recording has never been out of print, and Iíve worn out two LP

copies of it. This is at least its second restoration to CD, and,

if youíre asking, it sounds better than the first time around.

The mid range is cleaner, the bass is fuller (note the clear distinction

throughout between timpani and bass drum), and the highs are there,

too, clean but not clattery. Thereís no artificial reverb or brightening

like some of the DG restorations from the mono have. And the price,

just about exactly what the first LP pressings cost 50 years ago,

is, in terms of todayís currency value, utterly trivial by comparison.

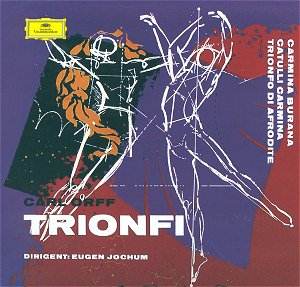

In

1953 this was a best seller, and Jochum eventually got around

to recording the other two numbers in Trionfi to make a

complete recording, and that is what we have here, complete for

the first time on CD. The magic wasnít quite there for parts 2

and 3, and I would be the last to speculate why. Really, the music

isnít quite as good, or at least quite as important, and

maybe thatís all there is to it. Other recordings by Smetacek

and Kegel, all in stereo no less, are about as good in these later

parts, but theyíre more expensive.*

If

you ever hear of my having suddenly and permanently been removed

to a desert island, donít come round my house looking to find

this recording. It wonít be there.

*There

does exist a recording of the prelusio only from Catulli

Carmina which sweeps away all competition, but that will make

a good story for another time.

Paul

Shoemaker

see

also review by Rob

Barnett