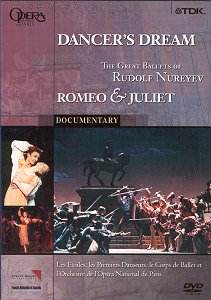

This

documentary film is about one third talking heads (live colour

video), one third ballet rehearsal (live colour video), with the

rest snippets from live staged performances (colour film) and

background images and historical footage (B/W). All the heads

talk in French, and even when an interview is in English, there

is a French voice-over. Sound and picture quality are excellent

especially considering that in most scenes original SECAM video

is converted to PAL for the disk and then to NTSC for my television.

As a result of this, in one brief scene of a very detailed black

and white engraving of the facade of a cathedral the screen was

covered in a checkerboard of scintillating rainbow colours—well,

it was kind of pretty.

The

scenario is that in 1995 the Paris Opera ballet is mounting a

revision of the Nureyev choreography of Romeo and Juliet,

and the ballet tutors, Patricia Ruanne and Frederic Jahn, both

of whom had danced with Nureyev in London and Paris, talk at great

length about how the changes they are making are fully in the

spirit of Nureyev and that their revered teacher would wholeheartedly

approve of their production. There is some historical footage

of previous productions, including a 1955 Bolshoi production from

Russian newsreels. Curiously, they say that the Russian productions

are not well documented: were they unaware of the 1955 Soviet

colour film of virtually the whole ballet?

It

is pointed out that Nureyev worked with Martha Graham in the USA

before he began choreographing Romeo and Juliet. He then

had a special interpreter go over Shapespeare’s play for him word

by word to be sure he understood every word of the play perfectly.

In particular, the characters of Mercutio and Tybalt were greatly

strengthened and the crowd fight scenes were brought to frightening,

dangerous realism. The energy of the dancing was brought to the

fatigue point for the dancers: "Rudolf wanted a step for

every note." "He thought like a film director, and in

the crowd scenes wanted something going on in every corner of

the stage." After working themselves to the point of collapse,

the best the dancers could hope to obtain from Nureyev at the

end of an exhausting day of rehearsals was, "See, you can

do it!" Oddly, Romeo is shown to be a passive character with

everyone else making decisions for him. While at first the English

critics decried this as an error, eventually it was seen to be

just what Shakespeare portrayed.

The

Italian stage designer Ezio Frigerio mentioned that Nureyev wanted

a realistic Italian Renaissance quality to the settings. "He

had strong ideas of what he wanted from looking at Renaissance

paintings, but I had to keep reminding him that I grew up with

the Renaissance all around me every day." Also, "Death

is always present in this work, and we had images of death before

us in every scene."

The

best part of the film is the rehearsals, watching these beautiful

young healthy dancers working their way through the actions one

at a time, with the tutor, then alone, then in ensemble, then

together with props, than in costume on the stage, sometimes cutting

from one to the other on a single beat. If ever you thought it

was easy to be a ballet dancer, this film will knock that idea

right out of you. And it also disposes forever of the image of

the effeminate male dancer. These guys are as tough as they come,

and in the fight scenes with swords and knives tremendous skill

and care were required to prevent serious injury. What I question

is whether this degree of violence was actually a realistic reflection

of Shakespeare’s experience of Elizabethan London (as Nureyev

claimed), or more likely the usual English tendency to portray

almost every other people as more violent and irrational. I remember

one critic commenting on what he thought was the excessive musical

violence and passion in Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet:

"Yes, they were Italians, but not Persians!"

A

most amazing revelation is that in this production the final tomb

scene was never rehearsed, it was left to the dancers to improvise

it, so it was different every time.

This

film is not a good way to become acquainted with the ballet. It

is assumed that the viewer is already familiar with the story,

the music, and the dancing, preferably from one of the Nureyev

choreographed versions. If you’re working on your French accent,

this film could help you with that, as it presents you with 89

minutes of varied examples of Parisian French, English accented

French, and Italian accented French.

Paul

Shoemaker