I

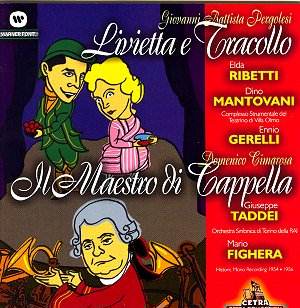

have often complained that the inadequate documentation of these

Cetra reissues has sent me scurrying to the Internet in order

to find out something about the performers. So congratulations

this time not only for good notes on the music and a synopsis

– as is usual – but also biographies of the three singers and

one of the conductors – nothing about Fighera, and I can only

add that he appeared regularly with the Turin orchestra at that

time. Not that Taddei will be a new name to most music lovers,

and opera collectors will know of Ribetti and Mantovani too, though

their appearances with the major companies were generally in minor

roles.

Where

Cetra have not changed is in providing us with the librettos in

Italian only, and I wonder if I would have enjoyed this disc as

much as I did if I had not been fluent in Italian myself, for

the slender plot of Pergolesi’s Intermezzo requires full understanding

of the various gags, as in the scene where Livietta speaks in

French and Tracollo, hearing a word or two here and there which

sounds like an Italian word, answers at total cross-purposes.

Italian speakers will also relish in full the delivery of the

recitatives, as natural and vivacious as speech itself. Another

gag is Tracollo’s singing falsetto on his first entry – listeners

not expecting this will think they are hearing a not very good

counter-tenor. Still, there are some nice arias – Livietta’s "Caro,

perdonami" is most imaginatively realised by singer and conductor

– and admirers of Stravinsky’s "Pulcinella" will hear

some familiar phrases along the way.

We

like to think that we have learned how to sing baroque music only

in the last two or three decades, but when both singers have such

bright, well-placed voices without a trace of excessive vibrato

or heavy-duty operatic delivery it is difficult to see what advances

have been made. The conducting is also clean and lively. Just

two features will date the performance a little. Very likely such

music would now be played with one string per part; and if a slightly

larger group were employed, there would still only be one double

bass. I’m not suggesting that the orchestra here is enormous,

but the sound is a little bass-heavy, in spite of the liveliness

of the playing itself. The other oddity is that, while a harpsichord

accompanies the recitatives, it stays silent when the orchestra

is playing. All the same, the performance is most enjoyable and

a valid tribute to the pioneering work of the Villa Olmo company

which revived no fewer than twenty-four works of this kind in

a single year. The recording is remarkably good for the date.

The

recording of Cimarosa’s little jeu d’esprit is more what

we expect from Cetra, the voice well caught and to the fore, a

rather woolly orchestra in the background. But it’s not bad and

the main thing is Taddei. Although he took on plenty of big roles

during his long career (Guglielmo Tell, Scarpia, Hans Sachs ...)

he was also a famed Mozartian and made a special study of baroque

vocal style. So he enters fully into the spirit of the piece without

ever seeming too big for the part. He was the first singer in

modern times to perform this work, for the RAI in 1953; the success

of this performance led to the present recording, which uses an

edition by Maffeo Zanon, who orchestrated the recitatives.

Here

is another piece where I feel that only listeners well versed

in Italian are going to get the most out of this sketch of a singer

rehearsing a not very co-operative orchestra but, again, a translation

would have helped. I have another reservation, but maybe this

is inherent in the piece. When the Maestro pulls up the various

sections – "What are you up to, my dear oboe? ... Damned

double bass, what the devil’s happening here? ... Please, oh please,

pay attention and learn to count properly ... " – the instruments

in question have actually been playing quite nicely. And conversely,

when he goes into raptures after the violins have got their little

phrase right, their performance here is unremarkable. I’m wondering

if the orchestra should have entered into the spirit of the thing

and played deliberately badly in order to be corrected more convincingly.

But on the other hand, would such a farcical approach, however

hilarious in a live performance, stand repeated hearings?

More

recent recordings have been made by Claudio Desderi, Fernando

Corena and József Gregor. The latter has an obvious coupling

in Telemann’s "Der Schulemeister" but has been criticised

for an exaggeratedly farcical approach; the other two come in

rather mixed company – Desderi in a rag-bag programme of "La

Scala at the Bolshoi", Corena as the filler for a complete

"L’elisir d’amore" where the conducting of István

Kertesz has found little favour. So Taddei sounds like the best

buy. A modern version of "Livietta" comes from Nancy

Argenta and Werner van Mechelen with La Petite Bande under Sigiswald

Kuijken, a very well filled double bill (80 minutes) with "La

Serva Padrona". But I think that opera buffs who get this

to add another Taddei performance to their collection will not

regret having the Pergolesi.

I

have mentioned the excellent notes, which are anonymous. Not so

the English translator, Nigel Jamieson, who gets into the booklet

three times over. But I wonder if his work was tampered with,

since entire pages go without a hitch, to be followed by some

very unfortunate expressions indeed. A recurrent grammatical mistake

comes in such sentences as "The Stabat Mater written

for soprano, contralto strings and organ, that immediately spread

throughout Europe, was transcribed ...". Unfortunately, you

can’t substitute "which" with "that" when

the relative pronoun is a non-defining one. And what are we to

make of this? "Ennio Gerelli, a trace of whose career

can still be found at the Municipale di Reggio Emilia in a Dido

and Aeneas performance by Purcell and in a Voix humaine

performance by Poulenc in 1970 ...". And I always thought

Purcell died young! Of course, even a perfectly competent translator

can come a cropper if music is not his subject. Thus we learn

that "Among the certain instrumental works by Pergolesi are

the Concert for violin, strings and continuous ...". Surely

anyone with a smattering of knowledge about classical music knows

that "concerto" and "continuo" remain unchanged

in English. Then we discover that Pergolesi wrote an "Oratory"

La Fenice sul rogo. But an "oratory" is a building

for prayer, a sacred story set to music is an "oratorio"

(the same word does for both in Italian). Curiously, the poet

Metastasio is transcribed into Latin as "Metastasius"

and it is explained that "Between the 15th and 17th century

the interlude, with praise and songs, included other spectacular

elements such as ballet and pantomime." If you don’t see

where "praise" comes into it, neither did I. Consulting

the original Italian text I find they are laudi, a type

of sacred song common at the time. There is no English translation

so the word must be left as it is, maybe italicised; any good

English musical dictionary will explain it.

Christopher

Howell