Marco Polo’s Guatemala series has been grinding

on now since Volume 1 was recorded in 1994 so you could be forgiven

for having lost track of it.

On that first volume is the four movement suite

‘Acuarelas chapinas’ translated I should say as ‘Four symphonic

scenes’. These were composed originally for solo piano c.1903

then orchestrated in 1907. The version for two pianos was arranged

as late as 1922 significantly and surprisingly becoming the first

music written in central America for that combination.

It has been interesting to listen to the two

versions side by side, although the Moscow Symphony Orchestra

under Antonio de Almeida (on Marco Polo 8.223710) plays as if

sight reading and that with their eyes shut. This beautifully

prepared version for pianos becomes, mostly, a much more pleasurable

experience. Basically the orchestral version is the same except

that the third movement is enlarged which I feel is beneficial.

Obviously the orchestra offer more variety although both pianists

find some wondrous piano colours from time to time. Despite the

fact that much of it is in little more than salon style it is

called Sobral’s masterpiece. We are told by Rodrigo Asturias who

has written the quite detailed (possibly over detailed) booklet

notes that it is symphonic in scope and form as far as tonality

and contrast is concerned. The four descriptive movements take

you through a typical Sunday in Guatemala City. 10.30 a.m. in

the park. 1 p.m. High Mass, 2 p.m. Cocktail hour, 5 p.m. (Dusk

in that part of the world) ‘At the Window’ including a particularly

memorable opening idea which develops into one of Martinez-Sobral’s

favourite styles – the waltz.

The waltz gives its name to another work the

‘Four Autobiographical Waltzes’ written at different times in

his life. I have to say however that there seem to be no secrets

hidden here that are in any way noticeable. These are salon waltzes

which Johann Strauss would have been proud of. The final waltz,

appropriately named ‘Autumn’, was the composer’s last instrumental

piece. It is the most memorable.

The ‘Five Characteristic Pieces and a Romance’

which opens the CD, consists of two Mazurkas, two Gavottes, a

Minuet and then the final Romance. These are romantic pieces neatly

assembled with thought for key contrast and logical development.

They were "put together" in 1920 but mostly pre-date

World War 1. The opening Mazurka and some aspects of the two Gavottes

easily bring to mind Chopin. The light-hearted second Mazurka

brought to my mind at least Cecile Chaminade (1857-1944).

I know that it is the house style Marco Polo

(to justify top price?) but the simple charm of these pieces is

unnecessarily deeply analyzed in the booklet notes where the most

appropriate response to this music is to sit back and let the

tunes flow over you. Only rarely do I think analysis unhelpful

and unnecessary but here I do.

The elegant pianism of Suzanne Husson seems ideally

suited to this easy-going music. She recorded another disc of

his piano music in the late 1990s (Marco Polo 8.225104) and so

understands what it takes to get the best out of it. She is most

ably assisted by Michel Bourdache in the best music on this mostly

unmemorable CD the ‘Acuarelas chapinas’.

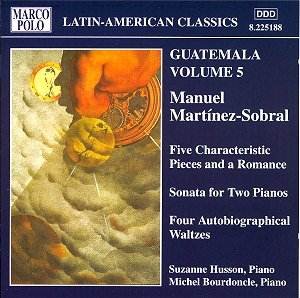

The delightful if somewhat abstract cover photograph

is of a painting by Arlette Asturias who is perhaps related to

the writer of the notes?

Gary Higginson

see

also review by Don Satz

Message received

Posted by Xavier Beteta

on February 24, 2004,

In response to the reviews posted by

Gary Higginson and Don Satz on “Guatemala

Volume V” I would like to clarify

some aspects regarding the Guatemalan

composer Manuel Martinez Sobral (1879-1946).

The works by Manuel Martinez Sobral

were discovered by the composer Rodrigo

Asturias in 1989. For a long time Martinez

Sobral’s music remained unpublished

and unknown and to some extent it was

considered lost. Before 1989 only two

works were fairly known of all Martinez

Sobral’s output and they were published

by “Gallet et fils” in Paris,

1955.

From different perspectives I would

say that Manuel Martinez Sobral occupies

a special place in Latin American musical

history. As a matter of fact, almost

all serious music composed in Latin

America between 1850 and 1950 has a

strong folkloric influence. In some

sense this “folklorism” could

be considered the “musical epidemy”

of that époque in the region.

In this sense, Martinez Sobral remained

neutral to this tendency, developing

a particular musical personality, being

profoundly Latin American (specifically

very Guatemalan) but not falling in

the excesses of folkloric references.

He could be compared to Edward Macdowell

who was educated in Europe, but developed

his own “american” musical

language without being folkloric.

Martinez Sobral’s music is full

of tradition. In his music prevails

the balance and the concept of the classical

forms. He was also influenced by Chopin

but by any means he could be considered

an imitation of the great polish composer.

For example, Martinez Sobral does not

present the “fioritures” or

ornaments so characteristic of Chopin.

To some extent Martinez Sobral created

his own personal “impressionism.”

His musical language is so particular

that it cannot be labeled under any

traditional style.

It is also known that his personal musical

library is still intact. From that we

know that he knew very well the music

from Bach to Liszt. Apparently he never

heard or had any contact with the works

of the post-romantics and the nationalistic

movements of the early XX century. It

is less possible that he had any reference

of the French Impressionism.

His musical craftsmanship was very

strong as it is shown in pieces like

the Acuarelas Chapinas, the final movement

of the Piano Sonata, the first piece

of the Evocaciones or the Vals Brillante

de Concierto (based on a ternary form

A-B-A combining rondo form and variation

form). This only gives us a sense of

to what extent Martinez Sobral approached

the real problems of composition and

musical creation.

His musical language shows great spontaneity,

being concise, flowing as a necessity

and focusing on a direct aesthetic pleasure.

It is never redundant or of “bad

taste” and his harmonies and musical

ideas present a particular refinement.

His melodic language has some relation

with the musical forms of the époque.

That gives as a result, memorable melodies

so easy to recognize. Of this type I

would mention Hojas de Album, piezas

como Danza, Tempo de Vals Lento, Mazurka

and Berceuse. Even, the first movement

of Acuarelas Chapinas presents a memorable

first theme that will be recapitulated

at the end simultaneously with the no

less attractive second theme.

Unfortunately Martinez Sobral had to

quit composing at age 42 to dedicate

himself to his other profession, law.

Now we know that the musical scene in

Guatemala of that time made him to take

this decision. There was a lack of interest

in musical culture in the Guatemala

of the 1920’s where dictatorships

were taking place one after another

destroying any form intellectuality

and artistic sensibility.

XAVIER BETETA

Composition, Musicology and Theory Division

College Conservatory of Music

University of Cincinnati