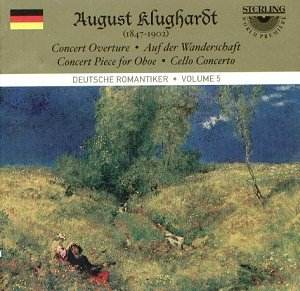

Born

in Cöthen in 1847 Klughardt’s life was suffused in musicality.

A piano soloist at sixteen (Mendelssohn’s G minor no less) his

studies took him to Dresden and to his teachers Blassmann and

Reichel - with whom he studied counterpoint. His early twenties

saw him on the move as a provincial conductor – he took a number

of successive posts around the country – whilst also keeping up

the piano. But it was composition that occupied him more and more

and the early grounding in Schumann became, over time, augmented

by admiration for Liszt, whom Klughardt knew, and Wagner, whom

he met at the first performance of Liszt’s Christus. Though he

was later to enshrine elements of Liszt’s tone poems in his own

works – which include a large number of piano miniatures, two

symphonies, a violin concert and a raft of chamber works – the

pieces on this disc, all derived from radio performances, reflect

much more the early rusticities of his Schumannesque musical persona.

These

are all attractive, well crafted and constructed with surety.

They are also attractively lyrical and ardent in a definably restrained

way. There are no undiscovered masterpieces but equally there

are some attractive discoveries. The Konzert-Ouverture has some

fine hieratic mountain top horn calls, some moments of contrapuntal

confidence (shades of Reichel) and plenty of nature poetry from

the School of Schumann – plenty of zest, plenty of good, honest

orchestration. The Konzerstück for Oboe and Orchestra is

a generous, verdant nine-minute affair, if somewhat conventional

in actual layout. There’s certainly room for attractive cantilena

in the slow section and the puckish oboe figures – contrasted

with the rather phlegmatic orchestral responses – enliven the

finale. The Cello Concerto is, in the spirit of the times, a single

movement, and multi-sectional one lasting eighteen minutes. It

was premiered by Julius Klengel in Dresden in 1894, the composer

conducting. Klengel was, with Hugo Becker, the leading cellist

in Germany and one of the most significant string players of the

day and it was a signal honour for the composer. Klengel was also

principal cellist of the Gewandhaus, a position he held for not

far short of forty-five years – maybe Klughardt’s early Dresden

connections paid off. The work is decidedly Schumannesque, full

of eloquent lyricism with a tune so delicious that Klughardt reprises

it almost immediately, this time varnished by pizzicati lower

orchestral stings – a miscalculation but an understandable one;

if you write a tune that good you want to hear it again. It would

have been better, though, to have embedded it as reminiscence

at the end of the work.

Auf

der wanderschaft is a six-movement suite of a decidedly verdant

kind. There’s plenty of nature painting in the opener, avian winds,

sturdy horn calls, all forest and stream. Der Jäger, the

fourth movement, is especially vibrant – hunting horns this time

and bird calls in sprightly collision. There’s a big boned waltz

as well – let’s not forget the dance floor – that leads straight

into the Gute nacht final movement; wistful, explicitly

Dvořákian and full of wind tracery. The Schumann melos is

still with us here though, warmly affectionate and ever lyrical.

The

recordings are getting on a little but they sound quite acceptable.

If your fancy leads you to the fringes of the Romantic repertoire

– don’t expect Brahms, much less Bruckner – I think you will find

Klughardt congenial company.

Jonathan

Woolf