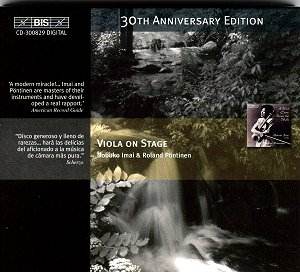

This

is one of those rare recital recordings that actually plays best

as a recital. Since each piece seems to lead so perfectly into

the next, I donít recommend jumping ahead to your favourite piece,

or what you think will be your favourite piece. It will sound

best played in sequence with the others. Taken as a whole this

concert comes across as quite a bit more than the sum of its parts.

Ms. Imai gives credit to Mr. Yukihisa Miyayama of King Records

for helping with setting up the program and for once I am ready

to take a bow to both of them for a job well done.

Quite

a number of these works are world premier recordings. The repertoire

for viola and piano is quite small (I think I have all the rest

of it on a single disk by Kim Kashkashian) and the range of styles

of these pieces is from lushly romantic to severely modern, from

furious, violent, drama to the quietest, most fragile meditation,

but each piece was actually published for viola and piano and

nothing has been hastily converted from music for other instruments.

The Britten arrangement of the Bridge piece is a published arrangement,

for instance.

I

think Toru Takemitsu actually achieved what Anton Webern was trying

to get at, that is, music which can be appreciated one single

note at a time with no sense of time flow. I actually enjoy much

of Takemitsuís music whereas Webernís music leaves me bewildered

and uninvolved. But although the album is named after the Takemitsu

piece, it is not the first on the record although I have shown

it as such in the heading for descriptive sake. The Takemitsu

is actually played between the Britten and the Rota, and it fits

perfectly there.

The

Enescu is appropriately theatrical, a good prelude. The Sibelius

is startlingly vigorous and passionate. The two Britten pieces,

especially the unaccompanied elegy, steadily but firmly move us

into an introspective mood so that for the Takemitsu we are ready

to listen with the crystalline attention required. From that the

Rota brings us back with some more symphonic, dramatic, tuneful

music in the form of a theme and variations. With the Milhaud

we go beyond friendly to the almost comical, with echoes of the

best of the Saudades, but coming to a surprisingly dramatic

finish, for Milhaud. All the better because the Persichetti, beginning

with a long cadenza for solo viola, is the quietest, noblest,

most eloquent piece Iíve ever heard from this usually noisy composer;

at moments it could be taken for Debussy! The Wieniawski has a

nice Nineteenth Century operatic lyricism with moments of heart-throbbing

urgency. The Bridge piece (based on a speech where Hamlet reflects

upon the death of Ophelia) begins in an atonal texture, and then

plays with our desire for triads and open intervals by moving

between close-in and far-out mysteryódemanding, as did the Takemitsu,

careful attention and in return giving rich rewards. The Liszt

is a late and very moody, reflective work, bringing the recital

to an elegiac conclusion.

In

the concert hall this would leave us in the mood for some brilliant

and rousing encores, but at home I think we can decide for ourselves

what, if anything, we want to hear next.

Paul

Shoemaker