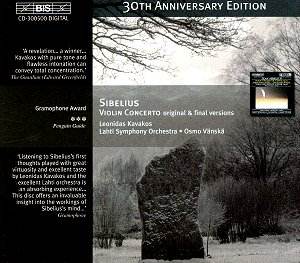

The

Sibelius family has taken a very protective attitude towards the

composerís papers; unnecessarily so considering that any number

of youthful indiscretions, false starts and the like could not

detract an iota from the mighty symphonies and the best of his

other works. Only very gradually have the archives been opened

up. It had long been known that the Violin Concerto (in common

with a few other works, most notably the Fifth Symphony) was first

presented in a version very different from the final one, but

only in about 1990 was permission given for this, and only this,

recording of it. Since it is to be the only recording, it would

have been terrible if it had not been a good one. Fortunately,

the performance of the final version is of such quality as to

set our minds at rest. At the outset I wondered if there was going

to be too much portamento, but this is countered by the silvery

purity of Kavakosís tone, which soars rapturously, passionately

and meditatively as required above Vänskäís dark-hued

orchestra. My one small reservation is that the finale, broadly

taken, could have greater impetus. Oddly enough, this matters

less in the performance of the first version where the major-key

material which Sibelius later expunged in itself lessens the impetus

of the music. All the same, this is a version to rank with the

best.

It

is a sobering thought that a professor of composition, if asked

to comment on the concerto in its original form, would probably

have told Sibelius to leave the second movement as it is (changes

are minimal) and prune the third (as was done), but throw out

the first and start again. To a lesser mortal, this first movement

really does seem too much of a ragbag of ideas to stand any chance

of being put in order. It is a most disconcerting listening experience.

It begins much as we know it, but before long we are in a foreign

territory entirely, and a strange one at that. It is not only

a question of there being many episodes based on material unknown

to us (and one of the orchestral episodes seems remarkably banal);

stranger still is when themes which know where they are going

in the final version sound here to be lost or to be leading in

another direction. The glorious second subject (as we now know

it) is present but only has a minor place in the proceedings.

It is quite extraordinary to reflect that only a year later Sibelius

was to develop this into the taut piece we know. If you love Sibelius

you will need to have this for the insight it offers into his

thought processes.

The

recording is a wide-ranging one; too much so in my opinion. With

the volume at a normal level I only realised the music had started

when the violin entered, so I turned the volume up and started

again. Yet some of the brass climaxes are excessively powerful

even with the volume back down to normal and I had difficulty

in finding a setting which could be maintained without adjustment

from beginning to end. The sound in itself is magnificently truthful.

Christopher

Howell