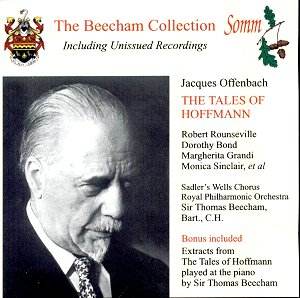

This set of The Tales of Hoffman is the

soundtrack to the famous Powell-Pressburger film of 1951 though

it was recorded at Shepperton Studios in 1947 for Decca. Looking

back at the Record Guide of the early 1950s and reading the review

of this performance – a bit of a stinker – prepared me for the

worst. But in the end I found much here that is compelling, though

it can’t be denied that the orchestral contribution is on something

of a different plane from that of the singers, a rather incongruous

multi-national bunch. Messrs Shawe-Taylor and Sackville-West were

in fine snickering form when they traduced the American tenor

Robert Rounseville as a Yankee college boy. Well, transatlantic

he may have been but that’s no impediment to suave characterisation.

In fact he’s perfectly acceptable if not outstanding. There’s

a bit of spread toward the bottom of his compass but he brings

energy to a role I could imagine would well have suited Heddle

Nash, rather better really than Rounseville. His Olympia is Dorothy

Bond, fearless in coloratura and strikingly dramatic. Margherita

Grandi’s Giulietta is perhaps just too elegant for the role but

Welsh bass-baritone Bruce Dargavel makes a strong showing; the

voice is not always perfectly centred but in compensation he has

bags of character and is one of the stars of this performance.

In the smaller roles we have a veritable cornucopia of emergent

talent; Monica Sinclair shows real embryonic talent as Nicklausse,

querulous, demanding and suitably assured; well-sustained bottom

of her range as well, even this early in her career. Owen Brannigan

takes three little roles being especially sarcastic as Schlemil,

Offenbach’s little joke of a name. Murray Dickie, later of course

a stalwart in Vienna, is here in the roles of Cochenille and Pitichinaccio.

One of the more intriguing turns – that’s the best way I can describe

it – is that of Grahame Clifford. Now Clifford was a famous member

of D’Oyly Carte’s troupe and there’s more than a whiff of the

London stage about his impersonation and patter. He does a fine

parlando act for example in There sleep in peace in the

First Act though I can certainly imagine that this won’t

be to all tastes and even more so is his eyebrow cocking G and

S knockabout in And now, Ladies and Gentlemen later on

in the Act.

There are other obvious points to note. There

are very heavy cuts and the opera is sung in English in the Arundell

translation. The Chorus is on firmly Anglo form in the Guests’

Chorus – more Marylebone than Montparnasse - but contribute their

relatively light share to the proceedings. The orchestra is on

song - really splendid. They are ebullient in the Prologue’s Finale,

percussion to the fore, brass ringing and are wonderfully alert

in Her reputation well deserved where Beecham allows woodwind

pointing of marvellous wit. The strings shine behind Rounseville

in his dramatic Act II Fair Angel and the principal clarinet

(Reginald Kell?) shines brightly in the Third Act No more to

sing alas. Beecham, of course, is the real star, a ringmaster

who had been acquainted with the work since at least 1910 when

he’d actually gone into the recording studios in his very first

sessions to record snippets from the opera (for Columbia with

Caroline Hatchard, Walter Hyde, Frederick Ranalow and Edith Evans.

Yes, that Edith Evans). His affection and dramatic impetus

are everywhere apparent, his control of tension and line, his

limpid accompaniments and eruptive Francophile drive. As an adjunct

and selected from more than two hours of surviving material is

a fifteen minute segment of Beecham going through the opera on

the piano whilst singing – the word is an approximation for the

sounds that are emitted by the knighted orifice – bits of the

score for Powell and Pressburger’s delectation (they didn’t know

the score; it was the conductor who had originally approached

them).

So in conclusion this is hardly likely to be

anyone’s first or fourth choice. It’s cut, in English, with some

quixotic voices. But the recorded sound has come up really very

well. There is joie de vivre from Beecham and orchestral excellence

as well as a treasurable sense of time and of place, which I found

frequently uplifting.

Jonathan Woolf