The

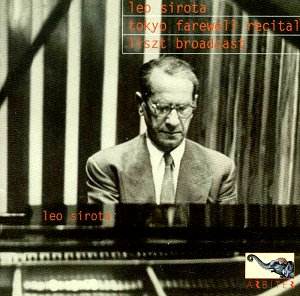

second of my encounters with Leo Sirota takes us to his Tokyo

Farewell recital made in 1963, two years before the pianistís

death. The Ukraine born Busoni student had come to the Italian

highly recommended by Glazunov. His Viennese start was auspicious

and he first visited Japan, then clamouring for Western classical

musicians (see the visits of Burmester, Thibaud, Szigeti, Butt

and many others) in 1928 intending a brief visit. He and his wife

stayed eighteen years. They were even there during the War when

they were evacuated to a remote location and lived in tough circumstances.

In 1946 he moved to St Louis to take up a position at the Institute

of Music. Sirota did record but relatively sparsely and his discs

have always been hard to track down; the existence, in various

collections, of fifty hours of Sirota broadcasts and performances

is a boon to collectors who have reason to be grateful that such

material is now appearing.

The

farewell recital began with the two Scarlatti pieces, the Pastorale

rather sleepy and rhythmically endangered, and the Capriccio slightly

better. His Beethoven Sonata grows in strength; itís true that

he can be capricious with the rhythm and that his thunderous bass

attacks (something of a trademark) can be over scaled but thereís

much here thatís immediately impressive. I like his way with the

contrastive material in the Scherzo Ė and one can almost feel

the increased confidence as he essays strong accents and shows

a real sense of style in his playing. As ever heís not note perfect

but then again he was seventy-eight. When he unleashes the bass

led torrents of the presto con fuoco finale itís certainly something

to hear.

Itís

in the Schubert that he reaches the apex of his playing in this

last recital. There is real sensitivity here and he brings out

the pensive introspection and increasing unease with acumen and

insight. There is a powerful sensibility at work in the slow movement,

a sense once more of stylishness but also of direction. Heís a

strong-willed and impulsive musician but adopts precisely the

right tempo for the poco moto indication. The Scherzo certainly

isnít, as we have seen from him, note perfect but it possesses

a pithy and dramatic quality that makes up for a lot and the Rondo

finale is most delightful.

Some

years earlier heíd recorded Liszt in one of his regular St Louis

broadcasts. These 1955 survivals show once more the cracks in

his technique Ė sometimes Sirota makes Cortot look like Horowitz

in that respect Ė but there are notable compensations. Thereís

a little tape damage on Sposalizio but itís relatively minor and

wonít curtail enjoyment. This is a rather slow reading and somewhat

italicised but it does have baritonal sonorities in the left hand

and the climax, though rather too late in the day, is strong.

The Don Juan Fantasy probably shouldnít have been attempted on

a technical level but Iím glad he did it anyway. For all the manifold

slippages and very splashy moments Ė and there are many Ė the

carapace of the interpretation is fascinating. Itís wonderfully

grand and declamatory, heroically charged and shows what a Liszt

stylist he was; maybe not one in Petriís class but then Petri

recorded much of his Liszt at a much earlier age. It makes one

wonder what Sirota would have done on disc with his Liszt just

before his Japanese sojourn say, when electrical equipment could

have done justice to his playing. But thatís one of those imponderables

that emerge when the body of an artistís work emerges in middle

to late age.

Once

more the Arbiter booklet is well written and full of documentary

interest and the photographs are both evocative and of good quality.

If youíre hesitating because of Sirotaís technical frailties,

donít.

Jonathan

Woolf