The sweltering summer of 1976, sprawled solitary in Hyde Park

with iced coke and secret Consulate menthol cigarettes, end of

term in sight, filling a battered diary with minuscule writing;

naive, voluptuous entries sentimentalising about unsentimentalisable

things. It was a time when everything was going my way, my uncle

was giving me regular money, the powers-that-be in the Royal College

of Music were starting to take notice of me, and most days it

looked like tomorrow might not come. A double piano and composition

scholar, I was in a little cosy world quite unaware of the opportunities

that would present themselves in the near future. After an uncertain

start, RCM life had become more enjoyable, I'd spent a year as

a resident of More House along Cromwell Road, made some good friends,

and I had completed the orchestration of my piano-duet work Nine

Pins, reborn as Symphonic Studies, which was taken

on board by the director himself, David Willcocks, and conducted

by him that autumn.

But before that, and to my astonishment, and

also indifference in many ways, I managed to win the 'Grade IV'

prize for piano, awarded for the best examination performance

of a student in attaining the top RCM level of 'V'. John Lill,

my retiring teacher, told me above the pub noise of the Queen’s

Arms (known as ‘the 99’ by RCM students) on the day I won 'You

have one over me, I never won that prize when I was a student'.

Could it really have only been the way I tripped

over my umbrella as I entered the examination room and showered

the three bemused examiners with scores of my compositions? Certainly

John Russell never forgot that moment, 'we thought 'we've got

a right one here''. The Brahms Handel Variations had already

become one of 'my' pieces, and together with Chopin's B minor

scherzo and something else, which I forget, managed to convince

John, 'Eddy' Kendall Taylor and I believe it was Alan Richardson,

that I should win that year's prize. (Despite memory lapse.)

From the moment I entered the room that early-summer day I was

aware of a truly benevolent aura, and felt drawn to it. Not to

mention John’s frequent blowing through the hole in his throat,

a constant reminder of his presence. I remember reading John’s

article about his operation for throat cancer ‘starting from

scratch’, and how ‘scratch’ had been the first word he’d had

to practise saying over and over after the removal of his voice

box. His disability was obviously irksome to him, but he coped

well, and for me, who’d never known his much-loved radio voice,

his burped speech only added to his stature and I clung onto his

every laboured and precious word.

John didn’t seem to understand why I wanted to

study with him after having studied with Lill for two years, and

neither could many others at the college whose tongues wagged

about it. But as I told John, who quoted me often, I didn’t want

to study with anyone who would tell me ‘to put my fourth finger

on C sharp’. Not that John Lill had ever told me to do such a

thing, although I remember the bleak days of my first term at

the RCM in 1974 when John Lill was on tour and his replacement

Neil Immelman told me many times to use certain fingerings; Neil

was charming, sophisticated and kind but I was so bored with the

technical pianism which seemed to obsess him and often left the

lesson holding back homesick tears. Lill wasn’t technical with

me, it was always a matter of demonstration and style, and in

that respect he had a lot of influence on me. The trouble with

pianists was that so few of them appreciated or even knew of much

English music. Most of the music I loved hadn’t been written for

the piano, so pianists’ discussions about other pianists, famous

recordings of the great piano classics and piano repertoire left

me cold. John Russell, though on the RCM professors list as a

‘2nd study’ piano teacher, was more appealing to me

than many of the other distinguished piano professors because

I sensed he would feed that strong desire within me to be close

to the English musical scene of the past, the time I never knew

yet felt nostalgic about, and would understand fully when I said

to him ‘John, I often feel I was born fifty years too late’.

Once it was ascertained that I really was sure

I wanted to study with him, John accepted and thus began a friendship

of fourteen years, until his death in 1990. Well, John was more

than friend, he was like a father. In fact he referred to himself

as my ‘mentor’. Only in name was he my piano teacher. He himself

said in a letter: I don’t teach so much as hold court. People

come in and out or stay – it’s just my style. It was a treat

just to be able to spend an hour drinking milk or scotch, smoking

cigarettes, chatting about everything and anything, but always

learning some new story or anecdote about his great friend Gerald

Finzi, or other assorted immortals from the past world of English

music’s heyday. Every lesson John would allow me to pianistically

wallow, perhaps in my favourite Elgar, busking big chunks of Gerontius,

until I couldn’t remember the next bit, at which point he’d slip

to the keyboard, cigarette hanging from his lips, and with tears

in his eyes busk a similarly big chunk of The Apostles,

exploding with exasperation, whale-like, through his breathing

hole at any mistakes, saying afterwards how it was ‘the greatest

of the three’. Sometimes I’d run through something I’d been learning

(usually English) to which John would give me one or two general

comments and that would be enough; such as of John Ireland’s Amberley

Wild Brooks ‘you play it like one big wank’… Thereafter my

rendition became more paced.

Thus he took me through my final two years at

the RCM, inspiring a new self-confidence in my ability as a pianist

and composer. ‘You HORRID boy, I can’t teach you anything’. He

would introduce me to other colleagues at the RCM as his ‘enfant

terrible’, and they would smile or laugh and marvel at our special

friendship. His first letter to me, a very typical example of

his style, began: My dear Adrian, Your letter has given your

elderly dumb friend more pleasure than he can express. As you

can well understand, it is easy to become possessive of a rare

talent such as yours, and that I have always been determined not

to indulge in. But I need not say that I’ll be around for just

as long as I can be of any use to you as mentor (look it up in

the dictionary) and for ever as a friend. So shut up.

As a ‘Brother Savage’, John soon introduced me

to the fraternity of gentlemen who wiled away many hours without

the possibility of an appearance by the wife. On many occasions

John and I hailed a cab outside the RCM after my lesson (one very

cold evening John truly frightening the cab driver with a coughing

fit resulting in a spectacular display of under-collar steam)

and headed off to The Savage Club, then in Fitzmaurice Place near

Green Park. I recall the first person I met in those revered,

dim rooms, propping up the bar – ‘Humphrey, this is one of my

worst students, Adrian Williams’ – Searle’s 2nd Symphony

had impressed me, although not knocked me out, at Watford Town

Hall years before, whilst elderly concert-goers squirmed. Krips

and the LPO doing Humphrey Searle in Watford – unthinkable now,

almost so in the early 1970s. The composer acknowledged me but

quickly resumed some involved conversation in 12-tone, furrowed-brow

cigarette haze. I attended a few dinner-jacketed Savage Club dinners

too, including one ‘ladies’ night’, all the boys on their best

behaviour. Ladies’ night concert, John in tearful ecstasy at the

piano accompanying Liza Lehmann’s In a Persian Garden with

a cluster of distinguished singers in relaxed mood, including

I think Margaret Cable and Marion Studhulme who I knew well at

the RCM. Then me crashing through Balakirev’s Islamey to

tumultuous applause and another guest Tanya Polunin saying ‘not

bad’. Midget comedian Wee Georgie Wood being carried onto the

little stage for some act. Then back to Reading by car with John’s

wife Margaret.

It wasn’t long after I came to know John that I was invited to

Ben’s Folly. John had lived in Reading for years and then in a

house large enough for their six children in Burghfield Common,

‘The Hollies’. Before I knew John came Ben’s Folly; Ben, the youngest

of the clan being an architect, designed the entirely wooden house

next door to The Hollies, set well back from the road with large

patch of land to the rear, sloping a little away to the west overlooking

undulating Berkshire fields. Margaret kept John in order with

a healthy diet, eggs from their own chickens, homemade brown bread,

jam, yoghurt. Everything organic and home made as far as possible.

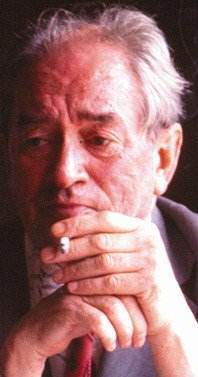

The author with the Russells at Bens Folly,

1977

The author with the Russells at Bens Folly,

1977

Even the rich Christmas cake which I somehow

came to ice for them, melting the marshmallows, mixing the paste,

peaking up the snow drifts, adding the little decorations; it

became an annual tradition for me to ice the cake, a good reason

to pay them pre-Christmas visits in later years.

The house creaked all the time, and one could

hear everything everywhere, but the atmosphere was radiant and

restful. John liked to just ‘be’

in his study, enveloped in an aura of tobacco and old paper, musing

over things, maybe scotch in hand, almost certainly cigarette.

If I went in, a score would come off the bookshelf, and an anecdote

woven around it. Like when the piano score of a certain concerto

work was processed over creaking wood through to the western-facing

lounge, and twangy Bechstein grand, and opened at the slow movement.

‘Play it’

said John with a silent grunt, expectation in his eyes, and as

I played, tears, as always, hiding just beyond flow.

Tears not so far away for me either; like discovering

new treasure it was as if a cellist were with us in the room,

that F-sharp rising to A, and falling chords anchored by the D

major scale. Finzi’s great late work (Cello Concerto) was hardly

known in the mid-1970s, like so many fine works by him and other

neglected composers. ‘We listened to the premiere on the radio

in 1956, while Gerald was in hospital.’ said John ‘The next day

Gerald was dead’.

This must be as good a moment as any to talk

about John’s close association with Gerald Finzi, which began

shortly after the second world war.

In the early 1980s John and I talked about the

possibility of publishing an article about "Russell and Finzi";

John very much wanted to write something himself, but an incident

shortly after Finzi’s death made him reluctant.

On June 7th 1981 John wrote a little

about it:

A horrible thing happened after Gerald died.

The local paper asked me for a piece about Gerald and me, so I

wrote an aide-memoire about the work we'd done together - which

they printed verbatim! Then people wrote and said cruel things

about "JR's conceit"....etc. So that's why the last 25 years have

found me silent, except for such people as your dear self who

have approached me.

From my reaction to this letter it seems that

John had been chewing over the possibility of writing an article

about Gerald Finzi and himself for some time, but hadn’t now the

courage to do so. I was slightly impatient and wrote the following

insolent note to John the same day I think 25 years is too

long to stay in one’s shell. The Finzis have behaved welcomingly

towards you…I wish you’d do the same and move towards them. Then

write that blasted article!! So shut up…..

But on August 24th John wrote: Adrian,

the more I think about the Finzi memoir (him and me, I mean) the

more I'm convinced that it should be by someone else, in the 3rd

person. The 1956 episode was VERY HURTFUL INDEED. The last one

wants is for people to assume that here is an upstart clinging

on to the back of a neglected composer (as he then was), and I

thought that the only thing to do in my misery was to keep on

playing his music ("Fall of the leaf", "New year music", Clarinet

Concerto, etc.), but keeping absolutely clear of personal association.

(The Finzi family made no move to get in touch at the time.)

Why do YOU not do a G.F.-J.R. piece? You,

of the next generation, are nearer to me and Gerald's music than

anyone else I know. You are in the picture, and I could give you

yet more details than we have so far talked about.

I don’t recall having received ‘more details’,

but on September 7th John came up with a short history

of his association with Finzi:

‘Here are a few

pathetic scribbles. Let the article speak via A Williams’

John Russell, the conductor and pianist, heard

Gerald Finzi's music for the 1st time by accident - it was the

cantata Dies Natalis at the 1947 Three Choirs Festival. He had

recently been released from six years of war service with the

R.A.F., and was out of touch with the world of music. These radiant

sounds led to a lifetime of devotion to Finzi's music.

They met (also quite by accident) later that

year, and the following 9 years were a constant adventure. Finzi

was a widely-read, cultivated man, whose activities in addition

to his own composing produced scholarly editions of 18th century

works by Stanley, Boyce, Mudge and others. His sensitive response

to poetry revealed itself in song-settings of words by Traherne,

Wordsworth and Hardy. Russell felt a bright new world opening

out to him, his moderate musical talent growing in range and in

depth. In 1948 Finzi recommended him for the conductorship of

the Newbury Choral Society, a post he was to occupy for 30 years.

In one season he persuaded the committee to agree to an entire

programme of Finzi's music - the Ceremonial Ode "For St.Cecilia",

"Intimations of Immortality", "Dies Natalis" and an unusual work,

the Grand Fantasia and Toccata for piano and orchestra, fierce,

discordant and dramatic. Russell played it and the composer conducted

it. Such was the success of this concert that Russell was emboldened

to repeat it at the Royal Festival Hall, with the LSO, and the

BBC Choral Society, with Richard Lewis and Peter Katin as soloists.

Thus one life was touched by the magic of

the man and his music.

In addition, Russell's growing family were

glad to take the advice of the family of Gerald and Joy Finzi

as to which type of schools they should send theirs to....

The Finzi connection found its way into my own

life, first through Lizbie Browne, that most gorgeous of

gorgeous songs from Earth and Air and Rain, in which I

accompanied Adrian Clarke at an audition for the late Sir Giles

Isham at Lamport Hall. The newness and freshness of that song

and its artlessly natural word-setting was totally burned into

my musical personality that day in 1975; also recalling misty-blue

Northamptonshire countryside.

My first meeting with Joy Finzi was in the late

1970s when I visited her in rural Berkshire with a friend who

was doing his GRSM thesis on Finzi. Then later on I joined the

Finzi Trust. Through this, connections between the Russells and

Finzis were re-established, though in a modest way. At about this

time another friend, violinist and entrepreneur Paul Gray, established

the Southern Pro Arte, the orchestra to which Joy Finzi gave her

blessing as successor to the then disbanded Newbury String Players,

and which had its inaugural concert at the Reading Hexagon in

1981. The late Marcus Dods was their principal conductor.

There was one memorable SPA concert in Newbury

Parish Church on October 3rd 1981 which included the

‘antiquated’ (Gerald Finzi’s

own description) Romance for strings, which is dedicated

to John Russell and which was included in the concert especially

for John. At the request of Joy Finzi Farewell to Arms

was sung by Julian Pike. John was present and wrote to me after

the concert, which had included a little work by me:

Adrian, my dear boy! It was only when I got

home on Saturday that I realised that you had got to where you

wanted, and where you ought to be - for a part of your life at

any rate - in the Finzi-Newbury-Russell ambience, and I had a

little weep. What better "visiting card" than your splendid music

(Do you ever cross ANYTHING out, or do you let it EASE itself

onto paper, as did Schubert, Mendelssohn, Dvořák

and (most of the time) Britten?) Gerald's restless soul must have

been singing with joy somewhere.

In March the following year, 1982, John reported

with delight in a letter that:-

Joy Finzi has made me a vice-president of

the new Finzi Trust, which cheers me after all these years (along

with D.McVeagh, J.C.Case, H.Ferguson et al) – a position made

more visible in August at the Three Choirs Festival in Hereford

at which the Finzi Trust held its first Three Choirs lunch in

a marquee near the cathedral. (Intimations of Immortalitiy

was performed at the Three Choirs that year if I remember correctly)

John and Margaret were both present, and, ever a willing slave,

I was commandeered to slice cheese for the buffet. John a few

days later: Strange Finzi gathering! I seemed to be without

doubt the only Elder Statesman present, except for Diana. [McVeagh]

The Three Choirs that year was an appropriate prelude to my move

from Surrey to the glorious Welsh marches the following month.

The

Russells, Hereford Three Choirs Festival, 1982

The

Russells, Hereford Three Choirs Festival, 1982

Indeed, continuing on from there, it was a fitting

honour to have the financial support of the Trust towards a recital

at the first Presteigne Festival in 1983 when I accompanied Brian

Rayner Cook in Let Us Garlands Bring.

John had, in his possession, the original manuscript

of Finzi’s Eclogue, in two

piano version, as it was intended to be the slow movement of a

piano concerto. As I pored over this treasure, I felt an almost

unbearable closeness to a time I never knew, a time between the

two world wars when Finzi was working in Gloucestershire, maybe

at Chosen ‘where westward falls the

hill’. Together with this gem were

collected the original of a hitherto undiscovered ‘Lullaby’

(Greek Folk Song) for SATB unaccompanied, and some scribblings

and a letter by Vaughan Williams about the double bass parts of

his Sea Symphony which John had performed with the Newbury

Choral Society one year. Sometime in the 1970s I took the M/S

of the Eclogue on one of the Welsh border holidays, so

I could be near it and near my spiritual home at one time! The

manuscripts are now safe in the British Library.

JR Eclogue

JR Eclogue

John told me the story of the Grand Fantasia

and Toccata, mentioned in his note earlier; how he’d

discovered the manuscript of the ‘Grand

Fantasia’ and the slow movement (later

to become the Eclogue), both parts of the unfinished concerto,

in Gerald’s house whilst on a visit.

It turned out that these had been written many

years before and were simply gathering dust. It was Russell’s

suggestion that Finzi wrote a Toccata to go with the Grand

Fantasia, and as the Grand Fantasia and Toccata John

premiered it as soloist in London in 1953. Needless to say we

bashed through it both ways on the two pianos of the westward-facing

lounge at Ben’s Folly, first me as the orchestra on the soft-toned

upright Broadwood, John clattering away his broken octaves, spluttering

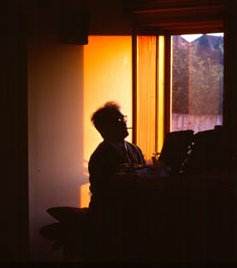

at the mistakes. Then, the Eclogue, charming, simple, John

with cigarette between his lips, an emotional silhouette against

the golden light of the south-facing window.

There came a time at the end of my first year

with John Russell (1977), when my pianistic ability was put to

the test. To my utter astonishment I managed to get through to

the final round of the Chappell Gold Medal competition at the

RCM ‘They didn’t

like you best’ grunted John with

a wag of his finger and a twinkle in his eye. I had already booked

my holiday … that went by the board, now I had to get down to

it. There were only three weeks and I had prepared nothing for

a 50 minute recital. But here was my chance to do anything I liked,

so I submitted an entirely English programme which John thought

completely ‘mad’.

Rawsthorne’s Bagatelles, Tippett’s

Sonata no.2, Ireland’s Amberley

Wild Brooks and April, Bax’s

Sonata no.4 and Grainger’s

Country Gardens and Shepherd’s

Hey. Of course in the eyes of most pianists it would be considered

madness, but I’ve never been one

for conforming to taste or convention. I loved English music and

felt it was still neglected. It was a tall order to memorise from

scratch this type of programme to recital level in three weeks.

Especially with hostile neighbours; my parents and I lived in

a typical suburban semi-detached house, and a small one at that.

Our twin neighbours were understandably irritated by my hours

of piano practise, especially when the master of the house was

on night-work and slept until mid-afternoon. It would have been

a disaster, but for John and Margaret.

So for three weeks in the early summer of 1977

I lived at Ben’s Folly in the Berkshire

countryside, practising for hours in the daytime gradually committing

my programme to memory, sometimes going down the hill for drinks

with John at the Hatch Gate pub in the village and talking to

Frank behind the bar, sometimes trundling down the same hill on

‘yellow peril’

the dilapidated old bike, sometimes driving their car in monotonous

circles on their driveway just for fun (I didn’t

have a driving licence in those days).

I recall a walk down through villages and past

remains of churches to Aldermaston one luxuriously warm day, catching

a train there and being picked up at Theale by John. A summer

gathering of family and friends, eating Margaret’s

kedgeree (brown rice of course) in the sunset glow with lounge

sliding doors open to the fields, and afterwards making a chorus

of little whistles out of cow parsley stalks, John blowing with

mirth in the midst. John loved visitors, old friends, family.

He often used to say ‘All I did was meet a girl called Margaret,

and suddenly the house was full of people’

A visit for a few days by the violist Bernard

Shore and his wife Olive, then already quite elderly, John and

Bernard performing for us Bernard’s

own arrangement for viola of Elgar’s

Violin Sonata, Bernard, Olive, John and Margaret with me

in a line for a treasured photo. And then Major Dent down in Hillfields,

aged 90, puffing to the piano by the windows overlooking great

lawns, and singing (shakily but not bad for 90) Quilter’s

O mistress mine to John’s or my accompaniment.

Bernard Shore and John Russell performing Shore's

own arrangement for viola of Elgar's Violin Sonata

Suddenly a jolly chuckle and dozens of little

explosions of ‘what?’

‘what?’

when he couldn’t hear something,

finally grunting off into the dark labyrinths of his mansion.

Then in the quietness of a summer’s

night on the balcony at Ben’s Folly,

Margaret with quilt and futon outside their bedroom, and a little

way along the balcony me with mine, both of us sipping Bournvita

under the stars. Then in the early morning the crowing of the

cockerel, Margaret descending the creaking stairs to let out and

feed the chickens, dew like silk on my pillow. Breakfast of muesli,

chopped fruit and yoghurt, maybe a new-laid egg, boiled.

And on a Sunday morning down to St James’s

in Reading for the Latin Mass. John’s

Catholic faith, sparked off by his friend the baritone Owen Brannigan,

was a constant source of solace to him, and I loved to watch and

listen to him stewing the Missa de Angelis plainsong into

romantic mush with his adoring little group of singers up in the

choir loft. Then after Mass an alcoholic introduction to the priest.

We usually arrived home some time after Margaret,

who had been to her Sunday Quaker meeting. Catholic and Quaker

- living more-or-less in acceptance of each other in the same

house, occasional teasing between the two.

Margaret’s Quaker

leanings suited her well, a skinny, bony, once beautiful lady

bred from a well-to-do family, still beautiful at times, matured

into a keen gardener and green-thinker. We enjoyed endless discourses

about ecological issues, my uncompromising youth tempered by her

life’s wisdom, her conversation calm

and her responses considered.

Somehow the lengthy stretches of piano practise

and memorising, broken by these glorious distractions brought

me to the point of readiness with my recital programme.

John was always close to tears at the swelling

of the big melody at the end of the Bax sonata; following his

reactions enabled me to know how to pace this section. I knew

when I had hit the mark. I always played on the Broadwood, which

I believe had been in Margaret’s

family, so much more mellow than the grand.

The day of truth arrived, Tippett Sonata no.2

98% memorised, telegram from John waiting at College: It’s

only the Chappell! Ordeal over. I was told that David Willcocks,

then Director of the RCM, had slipped into the back of the hall

astonished first to see one of the contestants for the Chappell

Gold Medal trip up the top step of the concert platform and lurch

across into the piano - only to give a hyperventilated crash-through

of English Country Gardens. I got the Hopkinson Silver.

Thank you Louis Kentner, Jimmy Gibb, Eddie Kendall-Taylor. It

was more than I had ever imagined for myself.

Then back to Burghfield, evening glow to the

west over rolling countryside, with the sort of satisfaction and

relief that only third place can give.

‘Fon’s Belly!

You horrid child’ wrote John,

reacting to my spoonerism; I could hear his explosive burps as

I read his letter. Those letters, like little friendly missiles

containing some small thought or anecdote or expression of affection.

His response was a photocopy of a competition from The Spectator

in which entrants had to be Lord Spooner himself, telling off

his slow undergraduates - ‘this

will make you splutter into your cornflakes’.

Indeed it did, what with ‘showing

tightness in your breasts’ but now

‘limply sagging behind’

or threatening to stop the authorities from ‘greying

your pants’…I can still hear John’s

own spluttering, loud blowing, accompanied by red face, watering

eyes, degenerating into prolonged wheezing and use of handkerchief

beneath collar. John was familiar with such old-fashioned English

tomfoolery, having known personally the inimitable Stanley Unwin.

The same letter went on: It reminds me painfully of a real

clanger. Yesterday I got a charming letter of thanks from Peter

Pears in reply to condolences on the death of B.B. – addressed,

of course (in his own handwriting) to "Ben’s Folly".

How clumsy can one get? O dear!

John had an enormous number of friends and admirers.

His welcoming warmth endeared him to all who met him. In my case

it was certainly that plus a healthy distaste for stuffiness which

drew us close as friends.

During the 1980s he was invited to become editor

of the RCM magazine, which publication suddenly became more approachable,

too much so for some. Even I was asked to contribute; an

article about Bernard Stevens’ 60th birthday concert

at the Workers Music Association … Many complained about the magazine’s

tone, saying it had become more like a student rag than the formal

RCM magazine they’d known. Maybe my childish offering hadn’t helped.

In the end John resigned. He fitted only very roughly into the

RCM establishment, but he loved time spent there, loved the company

of other musicians, those he’d spent his life working with.

Here is a lovely piece of observation in a letter

shortly after Bernard Stevens died: I enclose the Times obit.

Of Bernard [1916-1983] I assumed at first that E.R was

E.Roxburgh, but it is so unlike him and his style that I wonder

if it might be E. Rubbra, except that he’s coming up to 82! (Cripes!

Is he still alive?)

On Monday in the S.C.R [Senior Common

Room] there were Ridout, Horowitz, K.Jones and J.Lambert, all

discussing technical matters. I could almost see the wraith of

our dear ‘Elder Brother’ hovering over them.

He was larger than life-size among us, it

is cruel that all that vitality should be gnawed away by the relentless

CRAB. [Bernard Stevens had died of cancer]

I recalled how John had been delighted to be

given the all-clear for cancer some years after his operation.

‘You’re not going to die of cancer’ his doctor had told him. ‘What

will I die of then?’ ‘I haven’t the remotest idea’.

During the 1980s correspondence between us slowed

as I became ever more involved with ‘real life’ in the Welsh borders

and John and Margaret withdrew for longer periods into home life.

We sit quietly in the Folly the Friday about 7.30pm, Ma making

bread and me writing to you.

I managed to get over to ice the Christmas cake

occasionally.

His last letter came about four months before

he died: I’ve been 6 weeks and 4 to follow – treated for a

stroke. L H is useless and right leg is dragging and cannot stand

up if I’m sitting down. Write to me about you when you’ve time

and cheer me up. Love from us both …. PS Was with Edwin Roxburgh

when it happened in London. He got me back to Reading, saw me

into hospital and in fact saved my life! When I told him so he

said ‘John, don’t be daft, I just happened to be in the right

place…’

The end came that autumn; Margaret in her own

special way broke the news over the telephone, how John had suffered

another bad turn during the night …‘he didn’t survive’. It was

I who took John’s place in the organ loft, surrounded by the streaming-eyed

souls of his beloved choir. Missa de Angelis from above. Requiem

mass below.

Adrian Williams