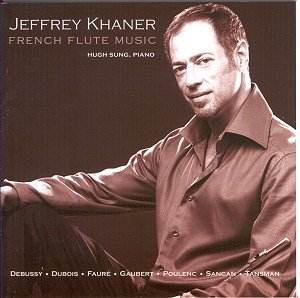

When

reviewing Jeffrey Khaner’s disc of American

flute music last year, one reservation I expressed was that

there was, understandably, a certain sameness about the programme.

That is equally true here; all the music tends to speak with the

same ‘accent’ as it were. This is not surprising, and it may be

that I am being unfair, and that the perceived sameness would

prevail in any selection of flute and piano music written

within a fairly tightly defined period; I don’t know. Notice that

I use the word ‘sameness’ deliberately, not ‘monotony’, which

would be misleading. But, to do it justice, I wouldn’t listen

to it all in one ‘go’.

The

programme is cleverly devised to include some staple items of

the flute repertoire – the Fauré, Poulenc and Debussy pieces

– interspersed with some less familiar music, including just the

one piece by a living composer, Pierre Sancan. In fairness, one

should say that the Dubois, Tansman and, in particular, Gaubert

works will be quite familiar to many flautists.

Khaner

is principal flautist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and before

that held the same position in Cleveland. He is thus a distinguished

player by any standards. What is impressive about him, though,

is his great musicianship and sense of style. His technique is

so secure that one feels that it is being put entirely at the

service of the music rather than the reverse, as can be the case

with some exponents of this instrument, which does lend itself

to fireworks.

The

Avie recording is more than acceptable, though it is interesting

to note that the engineers seem to have very slightly shifted

the balance between flute and piano as compared with the American

disc. However, the recording venue has changed, too, so some difference

in the sound picture is only to be expected. The result is that

Sung is a little further forward, and in places, e.g. the end

of the Fauré, seems to be having to play in a deliberately

restrained way to avoid drowning Khaner.

Nevertheless,

these are convincing and absorbing performances. The Dubois that

starts the collection is a most attractive piece. Its chirpy opening

recalls the finale of the great Prokofiev sonata, and it shows

the influence not only of Les Six, but of their successors such

as Ibert or Françaix. The middle movement is a slow, melancholy

waltz, which demonstrates Khaner’s fine tone, richly expressive

yet pure, with the minimum of that breathiness that can afflict

flute sound in the lower registers. The final Rondo is based on

a simple, good-natured tune, which is subjected to rigorous transformations,

before emerging more or less unscathed. This is an attractive

piece, entertaining though not too demanding on the listener.

The

Gaubert Sonata in A is a more serious-minded work, beautifully

written for the instrument, as you would expect from this composer,

who was one of the outstanding players of his generation, and

later became a famous conductor. The central Lent movement,

is memorable for its wide-ranging melodic lines, as is the main

theme of the finale, with its constant questioning cadences. The

duo give a committed, idiomatic performance of this exquisite

work; they have competition here, principally from Susan Milan

and Ian Brown on Chandos, but Khaner and Sung are in no way inferior

in their shaping and characterising of the music.

The

Fauré Fantaisie is a mere four and a half minutes

long, but, as one flautist commented to me, it can seem like an

eternity. From the listener’s point of view, however, it is sheer

pleasure, from the disconsolately side-stepped cadences of the

Andantino, (a link with the Gaubert there), to the effervescent

Allegro. Khaner, to his credit, makes it sound like no

trouble at all, and the contrasting lyrical theme sings out with

appropriate rapture.

I

confess to being slightly disappointed with the Tansman. I am

generally a great admirer of this Polish-born composer’s attractive

music. It is in five very short movements, giving it, as the booklet

notes (very well written and informative ones) comment, a suite-like

feeling. One could call it ‘bitty’ if one was feeling unkind,

and the level of invention seemed to me less than typical of the

composer at his best. The third movement, a Foxtrot with

oriental inflections, is the most attractive part.

The

Poulenc is easily the best-known of the sonatas on the disc, and

the most recorded, too. I enjoyed this performance, but my preference,

if pressed, is for Emily Beynon’s more sharply characterised version

on Hyperion. Khaner takes a very free approach, with lots of rubato,

which is fine, but can, and does, break up the flow of the music.

And a more serious problem emerges in the finale, Presto giocoso;

in the main theme (track 16, first 8 seconds or so), the tempo

is not maintained strictly, Khaner slowing down slightly but perceptibly

for the tongued semiquavers. This happens at the later reprises

of the tune, and is not to be recommended as an interpretative

detail! On the credit side, Khaner’s command of the very high

register, which much of this movement inhabits, is truly superb.

Pierre

Sancan’s short single-movement work is a delight. Its equivocal

opening reminded me a little of the Lennox Berkeley Sonatina,

and later he makes attractive use of flutter-tonguing, though

he resists the temptation to overdo it. The piano writing contains

many delicious touches (earlier in his life, Sancan was a distinguished

concerto soloist and chamber musician), and the interplay between

the two instruments is complex and symbiotic. I suppose the idiom

could be best described as ‘post-Ravelian’, but Sancan has his

own distinctive voice.

A

wonderfully controlled version of Debussy’s unaccompanied classic

Syrinx – there is no more magical music for summer evening

listening – completes this fine disc. It represents another splendid

achievement for Khaner, Sung and the Avie team. Flautists everywhere

will naturally rush to hear it, but it is full of great delights

for the ‘general’ listener (whatever that might be!)

Gwyn

Parry-Jones