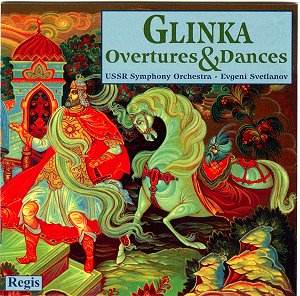

Glinka was a self-taught musical dilettante,

though in his time his talents earned him international stature:

Tchaikovsky once described him as 'the acorn from which the oak

of Russian music sprang'. Glinka studied in Italy for three years

from 1830, meeting Bellini and Donizetti, and then moved on to

Berlin for further studies on his way home. As result he was aware

of a wide range of western styles, and became highly skilled in

the techniques of composition.

This generously filled compilation covers the

range of Glinka’s achievement as a composer of orchestral music.

After the removal of his opera Ruslan and Lyudmila from the St

Petersburg repertory after 1842, he turned instead to composing

shorter pieces, particularly for orchestra, which therefore makes

this collection more valid still.

The recordings have been taken from a period

of more than twenty years, although all of them are at least acceptable,

and the more recent ones are much better than that. Svetlanov

was one of the great conductors of recent times, always capable

of producing a vivid performance. His directness and commitment

come across strongly in the two items from the opera Ruslan and

Lyudmila, recorded with the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra in the early

1960s. While the sound is not sophisticated the performances are

very direct and exciting, with a strong dynamic range and a rhythmic

bite that suits the music very well.

Svetlanov also makes the most of the colourful

Spanish Overtures that followed Ruslan in the 1840s. If his interpretation

of the first of these, based on the jota aragonesa that also inspired

Liszt’s Rapsodie Espagnol, is somewhat ‘over the top’, the vitality

of the music-making remains compelling. The recorded sound from

the late 1960s is equally colourful, though the perspectives are

rather larger than life. The arrival of the inevitable castanets,

for example, is emphatic in the extreme, though things do settle

down in the later stages.

All Svetlanov’s performances have an authentic

feel, and he has a sure touch also in the slighter pieces such

as the sequence of movements that served as incidental music to

Nikolai Kukolnik’s tragedy Prince Kholmsky. This music benefits

also from the best recorded sound, as it should with the more

recent vintage of 1984.

Congratulations to Regis for the standard of

presentation. Not only is the booklet beautifully presented, clearly

printed and well edited, it has the benefit of excellent and informative

notes by James Murray.

Terry

Barfoot