Enescuís

three Piano Suites chart the development of this most protean

of composers from 1897, his sixteenth year, to 1916. Whilst only

the last of them gives a foretaste of the mature Enescu of the

opera Oedip or the Piano Sonatas, all this music is imaginative,

vital and idiomatic Ė something only to be expected from this

most remarkable of musical polymaths, the composer-violinist-conductor

whose own piano technique was the envy of Alfred Cortot, no less!

Just

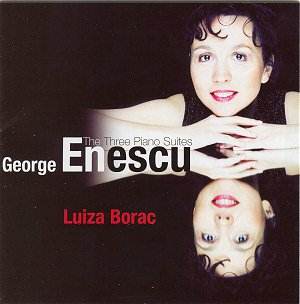

now Luiza Boracís Avie account has the field more or less to itself.

Aurora Ienei on Olympia is theoretically available but difficult

to obtain. Cristian Petrescuís, from his controversial but charismatic

3-CD set of the complete piano music on Accord, has been unaccountably

deleted; the Second Suite is certainly available in mixed

recitals by Monica Gutman (Claves) and Daniel Goiti (Symposium)

but neither of these is specially worth seeking out. Even the

composerís own recording of a handful of movements from the first

two suites has, with the demise of Dante-Lys, gone temporarily

underground.

Fortunately,

Boracís attractively produced CD is more than just a stopgap,

enhanced as it is by Martin Andersonís notes and a neat essay

on the technical difficulties of the Suites from the pianist herself.

If what Anderson aptly describes as the "crazy Bachian quality"

of the First Suite dans le style ancien is rendered

a touch somnolently, there is clarity in both playing and recording

to compensate. The disconcertingly bland Adagio is the

only movement where Borac stumbles, failing to catch its enigmatic,

deadpan quality. Here we certainly miss Ieneiís poise, compromised

though that was by Olympiaís tinny recording.

In

the more Frenchified neo-classical games of the Second Suite,

Borac treads equally cautious ground. Though the majestic opening

Toccata lacks nothing in grandeur thereís a hint of prissiness

about her over-pointed articulation. The wistfulness of the elegant

Pavane is brought out well, though partially at the expense

of that bercé (rocking) rhythm Enescu asks for and

captured in his own, more flowing version.

The

Pièces impromptues are not an integrated suite but

a collection of independent compositions written between 1913

and 1916. They inhabit a different sound world altogether, more

complex and personal, shot through the Slavic richness associated

with Enescuís later music. Most substantial are the linked Choral

and Carillon nocturne which close the suite, fading to

the sound of church bells echoing enharmonically through the Romanian

summer night. A magical effect, precisely evoked by Borac. The

reflective element in many of the Pièces suits the

personality of her playing well, though once again in faster movements

such as the Mazurk mélancholique (not enough Mazurka

and too much melancholia) rhythmic elasticity can be lacking.

This

is absorbing music, outstandingly recorded. If Luiza Borac does

not always rise to some of the insights of some of her earlier

Romanian compatriots, her interpretations are consistently lucid

and thoughtful. Especially given the absence of competition, this

is a self-recommending, quality issue.

Christopher

Webber

see

also review by Kevin

Sutton and Rob

Barnett