Of late we have had the opportunity to listen

to Merlin, Albéniz’s 1906 opera that has only recently

had its first fully staged performance (2003) at Teatro Real in

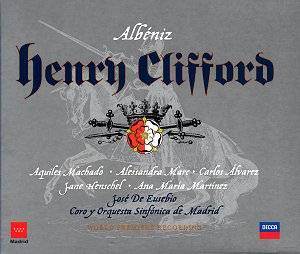

Madrid. Now Decca gives us Henry Clifford, his earlier, first

grand opera and one can now trace the composer’s operatic lineage

even further back, to the start of his artistic collaboration

with his librettist, Francis Burdett Money-Coutts, the aptly named

millionaire banker. The theme is the War of the Roses, the plot

appositely convoluted, whether warlike, confrontational, love-lorn

or verdant; the libretto frankly tosh of the most delirious kind,

and the greatest focus of interest is Albéniz’s orchestration,

which is particularly intriguing in its compound of late nineteenth

century and Wagnerian generic theatricality. One simply wouldn’t

know that it was written by him and in the context of an English

language libretto, listening blind, I would have hazarded a guess

at a German educated British aspirant to the domestic operatic

crown.

Albéniz was a London resident in the last

decade of the nineteenth century and his benefactor was determined

to establish English opera based on the Wagnerian model. The first

two Acts embody many set numbers and though the notes state, correctly,

that the third Act is more through composed there’s very little

effective distinction to be made. There are colourful roles and

plenty of opportunities for declamatory, histrionic and sensitive

singing. As I said the orchestral writing was, for me, the most

telling part of the work – the orchestral bridge passages in particular

are frequently deeply impressive – but set pieces abound and despite

the work’s deficiencies it gave me great pleasure listening to

it, cavils aside. One of those cavils I suppose we should note

here. Most of the cast are Spanish and I rather pitied their vocal

coach. The libretto is so besotted with plighted troth

and Away! Black beldame (it’s impossible to overstate how

truly appalling it is) that many of the singers, not unsurprisingly,

have some difficulty in pronunciation. Allied to which the sonic

sound stage is sometimes a bit skewed; some singers are more forward

in the balance than others. It would also be true to say that

the men have more comprehensively satisfying roles than the women

and that both are sometimes taxed by some strong demands on their

upper registers. This doesn’t sound like an easy sing and the

cast cope relatively well, though not comprehensively so.

There are a number of points of interest in the

score right from the colourful and dramatic late Romanticism of

the prelude, with its powerful strings and the medievalism of

the woodwinds. I said that there were no clues as to the composer’s

identity but maybe there’s just a slight prefigurement in Henry’s

aria and the duet with Lady Clifford O Mother why didst thy

deny my longing for the fray. And Albéniz really shines

in the Act I sequence following So am I quite unknown?

where the orchestration is marvellously expressive, central

European, with burnished horns and Wagnerian moulding. There are

certainly foursquare moments in Act I. The defeated Messenger’s

cry All is lost! ushers in a solidly blustery but unsatisfactory

few pages that only returns to form with the bier processional

tread announcing the death of Clifford’s father; noble and fine.

Again the inconsequentiality of the libretto and the uncommitted

hesitancy of the score lead to a rather lame conclusion to the

act.

The second Act opens in fairyland with some Mendelssohnian

material and is suffused in ballet generosity but before long

we get the heft of a love duet between Henry and Annie which brings

out some passionate singing though in truth the second Act is

no advance on the first and treads dramatic water for much of

its length. What stays in the mind is something like the scene

setting orchestral passage announcing the Earl of Richmond’s landing

or the stirring Shall loyalty to phantom right in the final

Act and Albéniz’s thoroughly professional approach to dramatic

highlighting.

So I wouldn’t rate this as a success in the same

way that Merlin was, but I would say that in its embryonic way

it sheds new light on Albéniz’s earlier compositional life.

To this end the booklet is extremely helpful, noting the historical

context, the textual problems and the production history. And

on a personal note, for all my strictures, I enjoyed it.

Jonathan Woolf

see also review by Lewis

Foreman

![]() Escolanía

de la Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos

Escolanía

de la Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos ![]() DECCA 473 937-2 [2CDs:

67: 08+72:29=139:37]

DECCA 473 937-2 [2CDs:

67: 08+72:29=139:37]