In

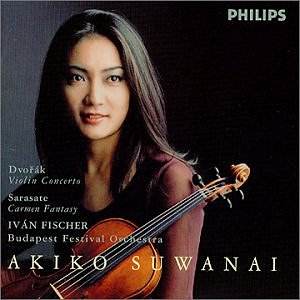

1990, Akiko Suwanai became the youngest ever first prize winner

at the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, and launched immediately

into an international recital and concerto career. Her début

recording of Max Bruch’s Violin Concerto with Sir

Neville Marriner in 1996 was highly acclaimed, and augmented her

already extensive international career as a soloist.

Her

latest album features two composers of nearly identical time periods

but very different professional and compositional backgrounds.

Dvořák was the son of an innkeeper and a failed violinist

who turned to composition in his thirties, emerging as Eastern

Europe’s most prominent romantic symphonist. Sarasate was a young,

internationally celebrated virtuoso violinist who spent much of

his life arranging opera arias and fantasies, only turning to

his own compositional career later in life. But both Dvořák

and Sarasate were strongly influenced by their native folk music,

and the compositions of each demonstrate an acute awareness of

this style.

Pablo

de Sarasate’s two most famous offerings open the album. The familiar

Zigeunerweisen ("Gypsy Airs") is the quintessential

showpiece, and one is immediately aware that it was composed by

a violinist. Based on Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies, the

opening section is an adagio featuring such tricks of the trade

as pizzicato and vast slides over the fingerboard. Ms. Suwanai

displays a wonderful dynamic range, capturing the overtly dramatic

style to great effect. The ensuing allegro integrates pizzicato

into the frantic melody, and this treacherous section is not executed

as flawlessly as in other recordings. Nor is the tempo as furiously

fast as in recordings by Heifetz or, especially, Ruggiero Ricci,

but is quite exciting nonetheless.

The

Carmen Fantasy is an abbreviated version of the

two Suites as seen through the eyes of Sarasate. This typifies

the composer’s earlier propensity for orchestration, using the

abovementioned acrobatic techniques as well as offsetting melodies

between soloist and orchestra and displacing themes by up to three

octaves. Sarasate has a seemingly inexhaustible arsenal of ornamental

ideas to spice up the already provocative dances, and Ms. Suwanai’s

abundant virtuosity is on full display.

Though

dedicated to Sarasate, Dvořák’s Mazurek is

a markedly different concept of the violin showpiece. A driving

Bohemian rhythm is the central idea, rather than a flashy, heavily

ornamented melody, and one can hear the heavy hands of a composer

in contrast to the fleeting fingers of Sarasate. But the Mazurek

has a charm all its own. Dvořák intersperses flourishes that

complement the melody rather than dominate it, and its more flowing

formal structure is quite cohesive. Even here, Dvořák’s symphonic

nature is evident. The accompaniment plays a more vital role,

and Iván Fischer and the Budapest Festival Orchestra shine in

this idiom. Ms. Suwanai is equally comfortable in this less common

work, and gives a beautiful performance.

Dvořák’s

Violin Concerto stands as one of the titans of the

romantic violin literature. Written for the legendary Joseph Joachim

(for whom Brahms composed his concerto), the Concerto underwent

an extensive period of revision before its première, illustrating

Dvořák’s awareness of the genre’s importance. It is

more symphonic in nature than a virtuoso tour de force, and requires

a rich tone to compete with the substantially scored accompaniment.

The orchestra opens with the rhapsodic minor theme, and, omitting

the extended introduction common to the period, the violin interrupts

with a more solemn thematic statement. Both Ms. Suwanai and Mr.

Fischer display a beautiful ensemble throughout the movement,

and the soloist displays an acute awareness and ability to by

turns dominate and accompany the orchestra. Brilliant technical

control and dynamic range mark this movement. Dvořák elected

to forgo a recapitulation and instead segues directly in to the

Adagio, a passionate and dynamic cantilena. The

Finale exhibits Dvořák’s affinity for folk melodies

with a giocoso, syncopated theme. The movement displays an array

of distinctly Bohemian rhythms, and the rhythmic precision of

both orchestra and soloist faithfully conveys its playful nature.

Mr.

Fischer and the Budapest Festival Orchestra have collaborated

for years on music of composers such as Bartók and Liszt,

always bringing a regional flair seldom captured by the more prominent

European orchestras. The winds stand out for their warmth of sound,

and the whole ensemble demonstrates an unsurpassed attention to

detail. Ms. Suwanai on this album seems to have gained a new level

of maturity and subtlety in her playing, and can surely be counted

among today’s most dynamic and talented young violinists.

Erich Heckscher