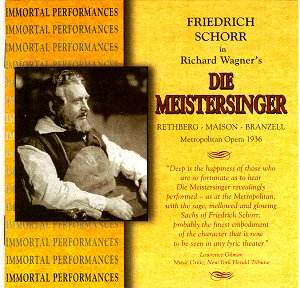

No doubting whom the star is here. The booklet

cover declares this is ‘FRIEDRICH SCHORR in Richard Wagner’s …’.

Note the capitals, here faithfully reproduced. Although Bodanzky’s

name is there on the box cover, it is completely absent from the

booklet cover. All of this is indicative of ‘Meistersinger

as the Friedrich Schorr Show’; 36 minutes of tacked-on excerpts

with other conductors under the umbrella heading of ‘Schorr as

Hans Sachs’ kind of confirm impressions. Sure, there is no doubting

Schorr’s stature, but let us not forget that the great Elisabeth

Rethberg is there as Eva, not to mention Emanuel List (Pogner)

…

Whilst Schorr’s Sachs was preserved in recorded

excerpts, no complete opera was recorded in the studios, so it

is to the broadcast archives we must go. Schorr sang at the Met

for a full twenty seasons (taking 19 different roles). This Meistersinger

was recorded with a single mike pick-up so perspectives can be

mobile as characters move around the stage. There are also some

cuts to the score, including the second verse of Sachs’ ‘Jerum’.

Guild have ‘slid in’ much of Sachs’ response to the crowds’ acclaim

(‘Euch macht ihr’s leicht’) from Schorr’s 1931 commercially-available

Victor 7682, altering the acoustic space to fit the present performance.

All this shows remarkable care on the side of Guild, and the result

is a glowing Meistersinger, not least because of Herr Schorr

himself.

It does take the ear a while to adjust, though.

The overture is shrouded in the mists of time, but it becomes

clear there is much dedication at work here. The woodwind peck

away nicely and in the main there is a serene lyricism. A pity

Bodanzky spoils the close of the overture, rushing in the final

pages and in the process spoiling the ‘surprise’ choral entry.

Perhaps this was in an attempt to foreground the lighter side

of Wagner, but it takes away the triumphant feel of the climactic

fanfares, and their pre-echoes of the close of the opera.

Schorr is magnificent, especially in the second

act. He is gripping right from the outset; the ‘Flieder monologue’

is exquisitely fragranced; and he is nice and lusty at ‘Jerum!

Jerum!’. The Eva, Elisabeth Rethberg, sounds tremulous at this

point (‘Guten Abend, Meister!’), but nevertheless remains touching

and delicate. If there remain finer documents of Rethberg’s art,

she nevertheless remains the epitome of youthful freshness.

But whatever Schorr’s strengths in the first

two acts, his art reaches its zenith in Act 3. The warm, dark

tone speaks of an all-knowing compassion in the ‘Wahn monologue’;

he remains the mainstay of this performance. Perhaps that design

was right after all …

Rene Maison takes the part of Walther. In Act

2 he sounds rather unfortunately like Mime, throwing Rethberg’s

lyricism into high relief, but the advantage is that both of them

sound youthful, as is entirely appropriate. The Act 3 ‘Morgenlied’

is confident and inspiring, as of course it should be. Eduard

Habich is Beckmesser, and very funny he can be, too. Emanuel List

is another famous name, here taking Pogner. Impressive as he is,

he can ‘crack’ at critical moments.

Julius Huehn is a powerful Kothner, if sometimes

a little approximate. Hans Clemens takes the part of David, a

role he was particularly associated with at the Met, and it shows.

This performance is six years into his Met career, and his confidence

is most impressive. Magdalene (contralto Karin Branzell, who also

sang Fricka and Waltraute at Bayreuth) is rich of tone and clear.

Bodanzky provides a reading which is always fluent

if not of entirely exalted nature. Not for him the heights of

a Karajan or a Jochum. There are memorable passages, however.

The Prelude to Act 3 is rapt and sonorous of utterance, attaining

a dignity and breadth that makes one wish the entire performance

were like this. The greatest shame is that the finale is not as

apocalyptic as it could be, a direct result of Bodanzky’s somewhat

limited vision. Despite many insights along the way, and many

pleasures (chiefly from Schorr), one does not emerge uplifted

at the end, and this is surely an acid test of a performance’s

effectiveness.

The Schorresque appendix is fascinating, even

if only approximate dates and only one source number is the sum

total of discographical information (is the Malchior/Heger excerpt

DA1227, for example?).

It is always good to be reminded of conductor

Albert Coates’ prowess as a Wagnerian, and his strong conducting

of another ‘Flieder monologue’ is welcome. Rethberg is on excellent

form in ‘Sieh’ Evchen!’ (VIC8195, December 1925). Coates’ direction

again triumphs in ‘Aha! Streicht die lene’ (May 1930), which is

lovely, and expansive in conception (if not necessarily in tempo).

How better to finish this ‘Meistersinger experience’ off,

but with the quintet , ‘Selig, wie die Sonne meines Glückes

lacht’, conducted by the miraculous John Barbirolli with a line

up that includes Elisabeth Schumann and Melchior. Here is miraculous

music-making, hushed and guaranteed to transfix.

Colin Clarke