Handel’s operas were frequently written for some

of the finest singers available. ‘Faramondo’ was produced in 1738

at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket after the collapse of the

rival Opera of the Nobility. This means that, unlike some of his

Covent Garden operas which were produced whilst his rivals performed

at the King’s Theatre, ‘Faramondo’ was written for a superb cast

which included the bass Antonio Montagnana sang the role of King

Gustavo and the castrato Carestini (making his London debut) in

the title role. Writing for such fine singers means that Handel

takes for granted the ability to sing virtuoso passages. In fact,

singers would have expected to be able to display their talents

in the requisite number of arias. These arias were crafted (or

fine tuned) once the cast was known, so that they take advantage

of the best points of a singer’s voice. King Gustavo’s arias takes

good advantage of Montagnana’s amazing range and all the singers

would have expected the divisions to lie in the best part of their

voices. Signora Antonia Merighi was a contralto profondo who sang

eight or nine roles for Handel, leaving us with a legacy of parts

with coloratura in what can be a difficult part of the average

female voice. And this is one of the eternal problems of casting

Handel operas. Finding singers who are not only up to the demands

of the part, but for whom the part lies in a good part of their

voice. With a complete absence of castrati, a remarkable lack

of low contralti and the presence of counter tenors, a voice type

Handel used sparingly in the operas, it is not surprising that

casting the operas nowadays is difficult. But a singer must be

able to do more than just sing the part. Handel’s arias are not

just vocal concerti, they illuminate aspects of the character

and a singer must be able to use the virtuoso passages to help

create character. So when listening to any performance, we are

constantly monitoring how the singers match against the ‘ideal’

performance. Whereas in Puccini’s ‘La Boheme’ we may have heard

what comes close to an ideal performance, in a Handel opera we

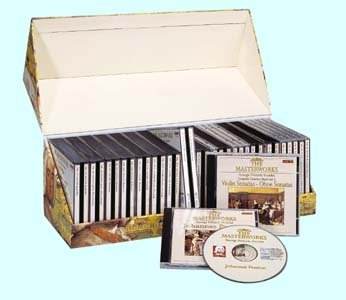

may never have the chance, not even on record. This recording

of Handel’s ‘Faramondo’ is currently the only one available, so

we must be grateful to Vox (who originally issued the recording

in the late 1990s) and to Brilliant. Whether the cast is ideal

is not entirely the question, it is more the way that they cope

that will matter.

Handel wrote his next opera, ‘Serse’ for the

same cast and ‘Faramondo’ can be regarded as the first of his

final group of operas. Handel’s final three operas (‘Serse’, ‘Imeneo’

and ‘Deidamia’) are all notable for a rather lighter feel. Whilst

none of them is strictly comic, one can feel that Handel was taking

a rather sardonic view of the whole opera seria genre. After all

this was the period when he was writing some of his greatest drama

in oratorio, for example ‘Saul’ was written the same year as ‘Serse’.

The plot of ‘Faramondo’ is a little convoluted,

turning on a series of relationships both loving and warlike.

Faramondo is at war with Gustavo and has already killed one of

Gustavo’s sons. Gustavo’s surviving son, Adolfo, is in love with

Faramondo’s sister, Clotilde. Gustavo’s daughter, Rosimonda, is

loved by and in love with Faramondo. Gustavo and his children

have sworn to avenge Gustavo’s son killed by Faramondo. Both Gustavo

and Gernando (initially an ally of Faramondo’s) are in love with

Clotilde. The drama plays out the character’s conflicts between

love and duty. Handel takes the drama totally seriously. In fact

the opera seems in many ways to hark back to earlier days when

he produced such serious works as ‘Radamisto’. But, ‘Faramondo’

is linked to the later operas by its shortness (the libretto was

heavily cut before Handel set it) and a lighter feeling in many

of the numbers. Much of the love music is particularly fine.

In the Montagnana role of Gustavo, Peter Castaldi

is reasonably efficient, with a tendency to smudge his passage

work and some rather approximate high notes. Castaldi does not

seem to have the capacity to give us a measure of the full range

of Montagnana’s voice and I think some of the lower notes are

transposed up. The title role is sung by D’Anna Fortunato. Here

her voice does not seem a good fit with Carestini’s; she does

not seem to find the tessitura of the role very comfortable. The

top can sound a little squeezed and the low notes effortful. She

uses rather more vibrato than I found comfortable.

As Clothilde, Julianne Baird has an affecting

voice, with a delightful trill. But her control in the fioriture

is not always ideal and she sometimes sings under the note. Drew

Minter as Gernando is singing the role written for Signora Antonia

Merighi’s low contralto. He over uses his chest voice for the

low notes and rather snatches at the top notes. Though apt to

be untidy, he is a stylish singer.

Jennifer Lane, singing Rosimonda, has a very

dark voice, I felt she could convincingly sung Gernando. Not the

most technically assured singer on the disc, she is nevertheless

a stylish one. As Adolfo, Mary Elen Callahan is more than adequate.

The small role of Childerico, sung by Lorie Gratis, was written

for William Savage. He had been a boy treble, singing in Oberto

in ‘Alcina’ and Handel would write the title role of ‘Imeneo’

for him when his voice had settled in a light bass. Here he has

a part written for him to sing in the soprano register (either

still as a treble, or more likely as a counter-tenor).

The opera is performed with some cuts, which

is strange given that the total running time comes in at under

3 hours. And even stranger, Acts II and III are prefixed by movements

from the Concerto Grosso Opus 6. Handel was in the habit of using

Concerto Grossi in the oratorios, but not in the operas. And both

of the acts have their own sinfonias anyway.

This is by no means a perfect recording. But

the Brewer Chamber Orchestra play stylishly and Rudolph Palmer’s

tempi are crisp and well chosen. Despite their technical limitations,

the cast believe in the opera and use Handel’s wonderful vocal

lines to create character, making us believe in the opera as baroque

music-drama; just as it should be.

What is needed is a modern recording with a star

cast. Rather than re-recording ‘Ariodante’, ‘Alcina’ or ‘Rinaldo’

could not someone give is a new ‘Faramondo.’ Until then, we must

be grateful to this recording which does its duty pretty well.

Robert Hugill