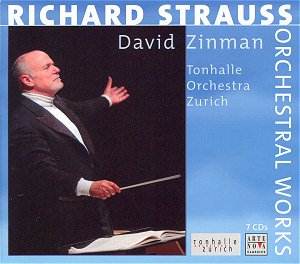

Richard STRAUSS

(1864-1949)

Orchestral works

Disc 1:

Aus Italien, Opus 16 (1886)

Macbeth, Opus 23 (1888)

Disc 2:

Ein Heldenleben, Opus 40 (1899)

Tod und Verklärung, Opus

24 (1889)

Disc 3:

Don Juan, Opus 20 (1888)

Till Eulenspiegel, Opus 28 (1895)

Also Sprach Zarathustra, Opus

30 (1896)

Disc 4:

Eine Alpensinfonie, opus 64 (1915)

Festliches Präludium, Opus

61 (1913)

Disc 5:

Metamorphosen (1944)

Vier letzte Lieder (1949) (Melanie

Diener, soprano)

Oboe Concerto (1945) (Simon Fuchs, oboe)

Disc 6:

Sinfonia Domestica, Opus 53 (1903)

Parergon, Opus 73 (1925) (Roland

Pöntinen, piano)

Disc 7:

Don Quixote, Opus 35 (1897) (Thomas

Grossenbacher, cello)

Romance in F major (1883) (Thomas

Grossenbacher, cello)

Serenade in E flat major, Opus

7 (1881)

Recorded: CD1: January 2000 CD2: January

2001 CD3: January-February 2001 CD4:

February 2002 CD5: May 2002 CD6: May

2002 CD7: January 2000 (Serenade), February

2003 (Don Quixote & Romance)

Venue: Tonhalle Zurich

ARTE NOVA 74321 98495-2 [7CDs:

CD1=65.27, CD2=74.28, CD3=65.48, CD4=52.36,

CD5=76.25, CD6=65.29, CD7=59.05]

Fresh from their successful

Beethoven cycle, which was most enthusiastically

received, David Zinman and his Zurich

Orchestra turn now to this substantial

compilation of the works of Richard

Strauss.

The new recording includes

both early pieces and music from Straussís

famous ĎIndian summerí. Throughout the

project there is no question that the

Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra play particularly

well, while the Arte Nova engineers

have produced an atmospheric acoustic

and a suitably opulent sound quality.

This is of course a combination which

is entirely right for this composer.

Among the earlier and

less celebrated works Macbeth

is by far the finest; in fact

it deserves a regular position in the

repertory. Zinman certainly has the

music's measure, generating real tension

and momentum as the drama unfolds. The

brass are perfectly balanced against

the remainder of the ensemble, and the

climaxes are potent indeed. Anyone who

enjoys the work's contemporary masterpiece,

Don Juan, will enjoy this, and will

find the music revelatory.

Aus Italien

is somewhat earlier, and here the teenage

composer is less assured than he was

to became in his twenties. That said,

the picture-postcard quality of the

work is never unappealing, though the

musical argument hardly sustains a work

lasting a full forty-five minutes. In

these circumstances it is tempting to

suggest that the performers might have

benefited from extra rehearsal time

before committing the music to disc,

since it needs all the polish it can

get.

The disc combining

Don Juan, Till Eulenspiegel and Also

Sprach Zarathustra contains three major

masterpieces, of course. Yet there is

no reason to be less than enthusiastic

about this version, which again shows

the Swiss orchestra and their American

conductor on excellent form, aided by

the rich and resonant Arte Nova sound.

The performance of

Don Juan has a real sweep

of momentum. Although the opening does

not have quite the élan of either

Rudolf Kempe (EMI) or Herbert von Karajan

(DGG), the attack and keenly articulated

ensemble remain of a high order. The

solo oboe is delicately coloured in

the lyrical episode, with the tempo

perfectly judged. The only real disappointment

is perhaps the great climax featuring

the horn section, since this seems a

little under-powered.

Till Eulenspiegel

is one of those pieces so rich in detail

that the problem can easily become one

of how to maintain a longer-term view

across the entire span. There are no

such dangers for Zinman here, since

he is so successful in reconciling the

different aspects of this most illustrative

of narrative tone poems. The highlight,

as Strauss surely intended it must be,

is the final scene of the hanging, which

is thrilling in its rhythmic confidence

and precision.

Also Sprach Zarathustra

is one of the largest of these symphonic

poems, and Zinman paces his performance

very well indeed. The famous sunrise

opening is recorded amid a sensitively

drawn atmospheric range, although the

organ sounds under-powered rather than

bringing a really climactic effect.

After that, however, the ebb and flow

of the complex lines of development

are expertly paced, and the sensitively

drawn final section is particularly

satisfying. At the Arte Nova super bargain

price, this represents a very competitive

issue, both in the single issue and

among the larger collection.

The coupling of the

massive orchestra of the Alpine

Symphony with the even more

massive orchestra of the Festival Prelude,

makes for an attractive combination.

Strauss composed the Alpine Symphony

during 1914-15, some ten years after

the completion of his previous large-scale

orchestral work, the Sinfonia Domestica.

This state of affairs had everything

to do with his successes in the opera

house, of course.

In the Alpine

Symphony there is an enormous

orchestra, including quadruple woodwind

and brass, an abundance of percussion

instruments, wind and thunder machines,

and even a 'distant' ensemble plus an

organ. All this is a reflection of the

resources Strauss lived with and had

come to expect in contemporary Germany.

The intention was to

translate into music his impression

of a journey on foot in the Bavarian

Alps, a choice of subject which was

no doubt inspired by his enthusiasm

for his new villa at Garmisch, built

out of the profits he had made from

Salome. Strauss uses his supreme

skills as a musical illustrator in evoking

every detail of his environment. The

progress of the mountain tour is reflected

in the structure - rising to an ascent

and then gradually descending again

- as well as in the manner in which

the themes develop. His mastery of the

orchestra is heard to magnificent effect,

and he knew it: 'Now at last I have

learned to orchestrate', he said.

There is no question

that Zinman has the measure of the scope

and scale of this work. There is always

a clear sense of direction and a well

articulated phrase structure. What is

less certain is the recorded sound,

which ultimately lacks a certain degree

of bloom in the string sound, something

which in this of all works is an important

issue. It remains the case, however,

that the listener is swept along by

the colour and even the sheer grandeur

of the music, though rival versions

by the likes of Karajan (DG), Kempe

(EMI) and Solti (Decca) offer greater

opulence.

The same might be said

also for the Festive Prelude.

This occasional piece was written in

order to precede a special performance

of Beethoven's Choral Symphony on

the occasion of the consecration of

the Konzerthaus in Vienna, in October

1913.

This building was constructed

on a lavish scale, the largest of its

three halls designed to accommodate

an audience of four thousand, and in

these circumstances Strauss felt compelled

to rise to the occasion and on the grand

scale too. He opted for some imposing

contrasts: as large a string body as

possible, huge wind and brass sections

with at least six (but if possible 12)

onstage trumpets, supported by the full

weight of the organ.

In the light of this

it is hardly surprising that the Festival

Prelude has remained an 'occasional

piece', impressive and imposing by virtue

of its sheer scale and grandeur. Inevitably

it proves so in this new recording,

even if the more powerful passages sound

a little strained. There are abundant

compensations, as Zinman and his enlarged

orchestra rise to the challenge this

epic work presents.

Disc five collects

music from what is rightly described

as Straussís ĎIndian summerí: Metamorphosen

for string orchestra, the Oboe Concerto,

and the celebrated Four Last Songs.

As far as the credibility of the collection

as a representative Strauss orchestral

compilation is concerned, some serious

questions arise here, whatever the quality

of the performances. For there seems

a certain laziness in the planning if

the Oboe Concerto is considered

valid while the Second Horn Concerto

and the Duet concertino (clarinet and

bassoon) are not. Likewise the later

pieces for large wind ensemble do not

appear.

Having come so near

to providing a complete Strauss collection,

it seems a pity that there remains some

distance before completeness is achieved.

The other major omissions are at the

earlier end of the Strauss canon: works

such as the First Horn Concerto and

the Burleske for piano and orchestra.

Back to the disc featuring

the later music in performances that

continue the high standards found elsewhere.

Zinman can have every reason to be proud

of the richly sonorous performance of

Metamorphosen, one of

the composerís most deeply felt and

keenly articulated compositions. So

too the Oboe Concerto is most sensitively

performed, with an excellent balance,

well recorded, between the solo of Simon

Fuchs and the string orchestra.

In the celebrated Four

Last Songs Melanie Diener is

a satisfying soloist, recorded in excellent

balance with a sensitively drawn solo

part. If to some extent her performance

seems under-characterised, it is probably

because the microphone does not unduly

favour her, while the personality of

her vocal tone is less distinctive than

some of her celebrated rivals. That

said, let us remember that a good definition

of a masterpiece is that it is greater

than any single performance of it. And

Dienerís performance certainly does

give satisfaction.

Disc 6 has an appropriate

combination: the Sinfonia Domestica

that Strauss completed while on holiday

on the Isle of Wight, and the little

known Parergon for piano

and orchestra that Strauss built out

of its musical material, more than twenty

years later. The progress of the Domestica

seems hampered by the indulgence of

a large tone poem created out of the

composerís domestic circumstance. Yet

the music itself explores ground unexpectedly

satisfying from so routine a source,

including some of Straussís most glorious

and radiant orchestral opulence. Zinman

and his orchestra relish their opportunities,

while the phrasing and tempi always

seem just right.

The Parergon

is more problematic, though Roland Pöntinen

is a skilful soloist, always in command.

If the music adds up to less than the

sum of its parts, this may be the result

of listening to it in the reflected

glory of greater masterpieces. Therefore

the domestic listener, having acquired

the whole set, might care to afford

this disc a special and careful attention.

The final disc (disc

7) is dominated by one of the greatest

of the symphonic poems: Don Quixote.

Weighed against Rostropovich or Tortelier,

Thomas Grossenbacher is a smaller personality,

but his playing has plenty of bight

and a character of its own that makes

the performance hugely rewarding too.

Yet again the Arte Nova engineers do

justice to Straussís wonderfully colourful

orchestral world. The variations move

onwards compellingly, the performance

therefore more than the sum of its parts.

Grossenbacher fares

well also in the little known Romance,

an early work lurking on the fringes

of the Strauss repertoire. The music

is slighter than in Don Quixote, of

course, but the results remain idiomatic

and satisfying. The collection also

finds space for the early Wind

Serenade, Opus 7. This too has

its own particular brand of personality,

aided by good recorded sound and a clear,

unfussy performance style. For here

as elsewhere in this ambitious collection,

Zinman shows how much he knows and loves

the music. While this is by no means

the only consideration for the prospective

purchaser, neither should it be ignored.

Romantic music, expressively and sensitively

performed, will inevitably brings its

rewards, and so it proves.

Seven CDs is undoubtedly

a major collection. There will inevitably

be some frustrations that the enterprise

was not more thorough in terms of repertoire,

and as discussed, there are some howling

omissions. Having made the point, let

me conclude by acknowledging the high

standards of performance and recording

that lie at the heart of this set. While

there may be a few regrets that it is

not as comprehensive as it might (as

it ought to?) have been, what we do

have is undoubtedly well worth having.

Terry Barfoot