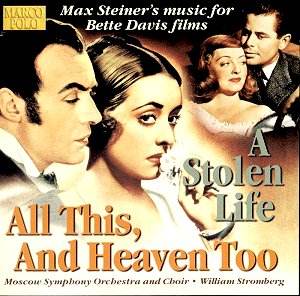

This is a marvellous disc. It’s packed with information

and insight and biographical details, with recollection and analysis,

added to which there are evocative period photographs and copies

of Steiner’s musical sketches complete with the visual cues ("He

stops"). And then there’s the music. Steiner, always one

of the most accommodating of film composers in that he favoured

through-composition, always makes for riveting listening and ensures

that the superb restoration by John Morgan makes not only for

a colourful and impressive one but also one that stresses the

cogency of the scores, especially the main focus of interest here,

All This, And Heaven Too, one of Steiner’s best Bette Davis

scores.

The 1940 score provides music for three quarters

of an hour in this restoration. Previous excerpts have really

been no more than snippets (Charles Gerhardt recorded a brief

selection nearly thirty years ago). Here we have a brash opening

Main Title followed immediately by some noble horns and entwining

strings, warm and mellow, in the cue beginning To France.

Steiner conveys the Carriage Ride with a degree of pensive

expectation before an almost syncopated gentility emerges in the

scoring, deliciously evoking mid nineteenth century gallantry.

He can even throw in the overture to Gluck’s Armida at

one point and has elsewhere a rich command of instrumentation

– in A Night to remember for Louise for instance behind

the thinned strings one can detect Steiner’s characteristic harp

and glockenspiel. To listen to Steiner at his most perspicacious

one should perhaps go to All Hallows Eve and the following

cues where nobility of utterance is immediately shattered by a

jeering, eerie chorus; Steiner’s lyrical arches work on the basis

of repetition and assimilation not on static cues and this makes

a work like this all the more rewarding.

His romantic gentility in this score is accompanied

by grim foreboding and foreshadowing (track 9 et seq) in a kind

of trio section before the effulgence of a near Mendelssohnian

moment of enchantment breaks over one. Steiner’s use of Tristanesque

allusions can be faintly traced in the despairing eloquence of

the eleventh track beginning Rushing to a Dying Duke and

the general musical ethos that Steiner evokes here becomes explicit

when he half quotes the puckish-tearstained end of Rosenkavalier

– indeed he goes further throughout the score where elements of

Le Bourgeois gentilhomme predominate and wittily so.

A Stolen Life dates from 1946. There’s

witty use of hornpipe material – the scene is by the sea in New

England - and again superb use of the harp. The cue Karnock

features some ominous lower string and bass clarinet writing

as well as suitably catchy, "shopping" music full of

delighted swagger. The Good and Bad sister motif is reinforced

by the music which posits freedom against insinuating sonorities

but there’s also some creative recycling going on here. Steiner

borrows some of his own music from King Kong for the evocative

storm music (the studio had wanted Debussy’s La Mer but

the fee asked was much too high).

These forces are fast becoming premier league

– indeed have long since become premier league – interpreters

of these kind of scores for this series. These are no run-throughs

and William Stromberg leads with delightful but controlled insight.

Most enthusiastically recommended to Steiner admirers.

Jonathan Woolf