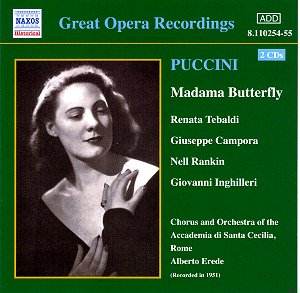

This Madama Butterfly is transferred from

Decca LPs, now out of copyright, and comes as a follow-up to Naxosís

recent transfer of Tebaldiís first Bohème which

I reviewed a few months ago. Opinions have been flowing freely

recently in the wake of a US Court ruling in favour of certain

Naxos transfers over which Capitol had claimed copyright and the

record companies themselves are lobbying for an increase to the

50-year copyright period operative in the UK and in Europe generally.

Some have even suggested that, since the company that originally

made the recording had paid for it, it should maintain its exclusive

rights for ever. Others argue on artistic grounds that the original

producer has the original tapes and can thus produce better results

than the likes of Naxos and Pearl (the latter have also issued

this Butterfly), who have to use LP pressings. Well, this

might be a valid point, so letís put the Naxos Butterfly alongside

Deccaís own transfer. Ah, but where is it? As far as I can ascertain,

this recording was last sighted on a pair of Decca Eclipse LPs,

debased by a process euphemistically called "electronically

enhanced stereo". (This is true as far as Europe is concerned;

there seems to be a transfer on the London label available in

the US. Commentators have complained of distortion on the high

notes, which I donít find here). As those-powers-that-be at Decca

have evidently judged this recording to have no commercial potential

these many years, what do they want an extension of the copyright

period for? To keep it under wraps for yet another 25 years? Or

50? Or for ever? In other words, an extension of the copyright

period might have some justification when the original producer

is still making the disc available to the public, but why should

it become merely an instrument for the prevention of public access

to recordings of historical significance? Perhaps a variation

of the law over Public Rights of Way might be applied; just as

a Public Right of Way can cease to be so if it is demonstrable

that no member of the public has attempted to use it for a certain

period, recording companies could lose their rights after 50 years

(or even sooner?) if it is demonstrable that they have not made

the recording publicly available for (say) at least five years

of the preceding ten. This would also act as an incentive to the

companies to reissue anything of value as the expiry date approaches,

to avoid losing it. (But de facto, this system operates

already; if Decca had put out a bargain CD transfer of this Butterfly

two or three years ago, would Naxos or Pearl thought it worth

their while to issue alternative versions?).

Turning now to the artistic question, access

to the original master tapes is clearly an advantage, but it still

depends on what you do with them, always supposing they are in

a good state (tapes deteriorate and develop print-through, so

it is possible to imagine cases where a pristine LP would be better).

Presumably Decca would not inflict "electronically enhanced

stereo" on them any more, but some of their own transfers

(such as the 1954 Kleiber Rosenkavalier) seem to have tried

too hard to find upper frequencies that just arenít there, producing

the aural effect of a paint-stripper. In this case, the musicality

of a Mark Obert-Thorn or a Ward Marston working with good copies

of the LP is much to be preferred and I wonder if they are making

plans for Rosenkavalier when it enters the public domain?

Better still, maybe, would be for Decca to hire Mark Obert-Thorn

or Ward Marston to work with the original tapes, but evidently

they think otherwise.

Anyway, here we have a recording in the fine

acoustic of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia, Rome, in which the

voices reproduce well and naturally. The orchestra is slightly

backward and the upper strings sound thin but I found this no

bar to enjoyment.

Renata Tebaldi has been considered, over the

years (both here and in her 1958 stereo remake) rather too tough

and bossy-sounding for the fragile little Japanese heroine. The

trouble is, Puccini just didnít write for fragile, evanescent

voices. Furthermore, while Butterfly may seem a naïve, clueless

little thing at the start, she grows in strength and resolve as

she prepares for the final tragedy. The sort of singer who might

sound suitably young and fragile in the opening exchanges will

be swamped by the tenor in the love duet and will simply not have

the resources for the rest of the opera which needs heft, heft

and heft again. Clearly this was not a problem for Tebaldi and

she rises to every climax with opulent, unforced tone. But, if

this implies a lack of tenderness, I donít really agree. Itís

true that she sings "The Japanese gods are lazy and obese"

with the air of one whoíd like to get hold of them and bang their

silly heads together, and I didnít find her especially affecting

in "Un bel dì", but many, many of the tender

passages, sometimes just a simple phrase here or there, are illuminated

by her exquisite soft singing. Iím inclined to think that you

wonít find a better sung Butterfly anywhere (though a comparison

with the longish extract from Leontyne Priceís 1964 recording

which recently surfaced in a double CD pack of that singerís Puccini

and Strauss suggests that at least one may be its equal), and

as a portrayal it has a lot in its favour.

Giuseppe Campora (b.1923) appeared regularly

at the Met between 1955 and 1965. He sings naturally and musically,

with no forcing of his attractive, lightish voice at climaxes.

Thus far, so good, but I think one wants a little more, and nothing

he does remains in the memory. Pinkerton is never going to be

an attractive character, but that doesnít mean he has to be faceless.

Richard Tucker, alongside Price, has plenty of character, although

he sounds a bit old for the part. I donít have the 1958 Tebaldi

to hand but the presence of Carlo Bergonzi sounds promising.

The Sharpless, Giovanni Inghilleri (1894-1959),

had a long career behind him (he had recorded Amonasro in 1928)

and has patches of unsteadiness, but he "uses" his elderly

sound creatively to make an attractive character of the Consul.

I donít know why it was thought necessary to bring in a Suzuki

from Montgomery, Alabama when plenty of Italians were at hand

(Giulietta Simionato recorded for Decca in this same period; in

1958 Fiorenza Cossotto took the role); in the event Nell Rankin

sings well enough though her Italian is slightly thick-sounding.

However, the only member of the cast that I found actually inadequate

was Melchiorre Luise (1899-1967) who offers a very wooden Prince

Yamadori (but itís a tiny role).

When reviewing Bohème I felt that

Alberto Erede was an underrated conductor and here again he shows

a complete understanding of Puccinian ebb and flow. Tempi are

quite swift, but with much flexibility and breathing space within

them; the singers are never pressed and the music always flows

naturally. He doesnít demand the ultimate in precision but the

Santa Cecilia Orchestra, Italyís best at the time, has all the

right colours and some very sweet-sounding strings. Since then

a varied assortment of "greats" have set down their

thoughts on Puccini conducting, often with a heavy hand. Tebaldiís

1958 recording was conducted by Tullio Serafin.

So all-in-all this set could still be a good

choice for a cheap way of getting to know the opera; great singing

from Tebaldi, adequate singing, sometimes more, from the others

and an excellent conductor. Tebaldi fans will be glad to have

it and will be pleased to have the four arias from 1949 as a makeweight.

The Gounod "Jewel Song" is perhaps the most interesting

in retrospect, since it shows that the young Tebaldi could sing

as a light and frothy operetta soprano; a few years later I doubt

if she could have sung it again this way. There is a good presentation

from Malcolm Walker, including biographical notes on the singers

and conductor; no libretto but a quite detailed synopsis.

Christopher Howell