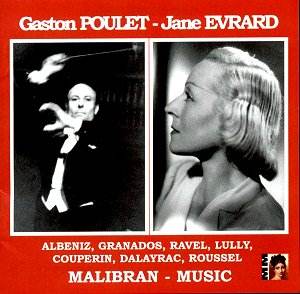

Malibran has cultivated a happy knack of conjoining

musical coevals or mutually sympathetic pairings. In the case

of this fascinating disc there was an even greater imperative

– these two violinists were husband and wife. Poulet is by far

the better known and many will recall his name as the young violinist

who premiered Debussy’s 1917 Violin Sonata in the Salle Gaveau

in Paris, the composer accompanying. A serial prizewinner as a

youth he had a duo with Yves Nat, formed his own highly regarded

quartet (on the advice of no less than Fauré) and was encouraged

to pursue a career as a conductor by Toscanini ("You, with

your eyes, you will become a conductor!") He began in Paris,

toured South America, returned to the south of France where he

formed an orchestra in Bordeaux whilst also heading the prestigious

Colonne Orchestra. As a violinist he recorded with his quartet

but made no discs as a soloist. His recording with Ferras of the

Elizalde violin Concerto has recently reappeared on Testament

and older collectors will remember his collaboration with Menuhin

in Saint-Saëns and Poulet’s own highly impressive violinist

son Gérard on Remington. He died in 1974.

His fairly meagre discography has here been supplanted

by what appears to be private recordings made at the Besançon

Festival in 1948. They are in remarkably fine shape and boast

impressive frequency response. It helps in addition that the repertoire

was so congenial to a Frenchman of his generation and as a string

player one who bring colour and expressive breadth and imperishable

style to his performances. He clearly wasn’t a powerhouse conductor

– more a colourist and subtle delineator of orchestral shards

and strands and these performances reflect well on him and the

orchestra. His Albeniz is evocative and brings out some really

individual and fine playing from the strings, the muted trumpets

and percussion (in El Puerto) and the noble rounded brass in El

Corpus en Sevilla where he extracts colour at every turn. There

is strong, snappy rhythm in El Albaicin and plenty of glimmer

and glint. He’s tautly expressive in the Granados and in the Ravel

one can admire the agility of the flutes and brass and the sheer

stylishness Poulet cultivates.

Jeanne Chevalier met Poulet at the Conservatoire

Nationale de Paris and they married in 1912. She was playing in

her husband’s quartet on the famous occasion when Debussy announced

that they were playing his Quartet rather differently from the

way he’d expected but from now on that’s how it should be played.

Gradually Jeanne – or Jane Evrard as she was to become – formed

an all female chamber orchestra that explored early repertoire

(Gretry, Couperin) and also did sterling service by premiering

new work by such as Honegger, Schmidt and indeed the Sinfonietta

by Roussel, which is preserved here in a 1956 radio broadcast

– she’d also recorded it for HMV in the 1930s. Her portion of

the disc highlights those twin strengths; the ancient and the

up-to-date. Her Roussel is resonant and expertly judged, catching

both its saturnine and piquant depths, the twenty-two strings

lithe and lean. Her Lully has plenty of old fashioned charm, dramatic

rallentandi and an audible harpsichord and the Dalayrac is a piece

the Krettly Quartet recorded (probably Evrard knew it from her

own experience in her quartet). The jewel though is the Couperin.

There was something of a mini explosion of interest in Couperin

at the time in Paris; new editions had been published and recordings

were now not entirely uncommon – Landowska led the way but Alice

Ehlers and Yella Pessl all recorded Couperin on the harpsichord

and a number of vocal and instrumental works had been recorded.

Nevertheless in an analogue to Nadia Boulanger’s almost contemporaneous

exploration on record of Monteverdi (which also featured Hugues

Cuénod) this is a most moving exploration of the Troisième

Leçon de Ténèbres. Its ability still to move

is based on the very obvious sincerity and sense of purposeful

delicacy the forces bring to the work, in all their romantic engagement.

Its imperfections seem to me trivial in comparison and the way

in which the solo trumpet courses and winds its way behind the

melismatic chorus is still a thing of wonder.

The notes – in French and English – are by Manuel

Poulet and the disc as a whole sheds fascinating light on a previously

under explored area of French musical life.

Jonathan Woolf