Everything

you’ve ever heard about Peterson-Berger’s piano music – if you’ve

ever heard anything about it – is true. Whereas the symphonies,

though attractive, want for real symphonic profile, in his piano

miniatures the sheer untrammelled romantic lyricism that so saturates

his music emerges unmediated by striving or grandiloquence. This

is a disc of pastoral bedecked pleasures, its open-hearted effulgence

occasionally joined by moments of unease and incipient tristesse.

But, mostly, all is well and the earliest of the Books, written

in 1896, catches him at his freshest and most winning. Peterson-Berger

was twenty-nine when the first Book was published and, dangerously,

a music critic.

Opening

warmly, the first book embraces late Romantic lyricism and Grieg-influenced

subtleties of infection – harmonic and otherwise – and Chopinesque

directness (try the fourth in the first book Till rosorna

and you’ll be puzzling who could have written it) as well as an

avuncular little gavotte and the limpid nobility and concentrated

grandeur of the sixth. Cleverly Peterson-Berger rounds off the

first cycle of miniatures with an affable but somewhat sad Hälsning

that seems pretty clearly related to the opening piece and adduces

another, deeper level of meaning to the work. The second book

followed four years later and is comprised of six miniatures,

again starting with a confident opener, and stresses the hymnal

and meditative air with increasing regularity. There’s forest

music as well with elfin folk music trio sections and real elastic

pliancy in the last two of the set. The Third Book (1914) was

inspired by a house he had built which he called Sommerhagen.

As the pianist hammers away we become aware that Peterson-Berger

is actually depicting the nailing and hammering of his sommerhagen

and the Förspel takes on something of a riotous air. But

he can’t escape pianistic nobility of utterance for long and his

Schumannesque-Grieg inheritance is most explicit in the second

of the set. There’s colour, emphasised through depth of bass tone,

and also witty and amusing folk dances and, as the Book comes

to a close, a quiet calm, a heat haze stasis.

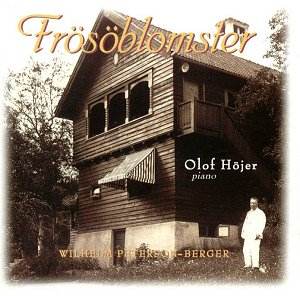

Really

fine performances by Olof Höjer are happily complemented

by his own sleeve notes and the natural perspective – warm, not

cloying – of the recording. Not to be taken in one go, maybe,

but a book at a time. There’s much here that is treasurable.

Jonathan

Woolf