AVAILABILITY

www.biddulphrecordings.com

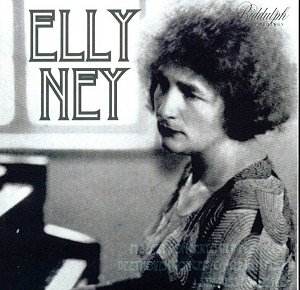

Of all the musicians tainted by their actions

during the Second World War few could have seen their reputations

sink lower than Elly Ney. A fanatical Hitler worshipper her appearances

after the conflagration were mainly peripheral and the reputation

she had earlier built as a concerto soloist, Beethovenian of the

first rank and powerful chamber player pretty much evaporated.

That she really was a player of sometimes quixotic distinction

can be verified from her surviving recordings, not least those

with her own trio and expanded quartet (the players included Florizel

von Reuter, Walter Trampler and the cellist Ludwig Hoelscher with

whom Ney was to record some of the Beethoven Cello Sonatas on

LP).

Ney was born in 1882 and had an outstanding tutorship

culminating in studies with Leschetizky and Emil von Sauer. She

taught briefly but her drive as a concert soloist saw her lauded

as early as 1909 and marriage to Dutch born violinist and conductor

Willem van Hoogstraten saw her embark on a duo career as well.

Internationally she visited America regularly and was a visitor

to the London Proms – though in London she tended to get asked

for the Tchaikovsky B minor in preference to her Beethoven. She

seemed for a time to occupy a position vis-à-vis Beethoven

that Frederic Lamond had slightly before her and Schnabel was

to do shortly afterwards.

Biddulph’s conjoining of these concertos demonstrates

many of these central strengths. Above all we can sense her appositely

characterised responses to each of these very different works.

In the Mozart for example, with an unnamed orchestra not of the

front rank under van Hoogstraten there is a rare feeling of engagement

and metrical daring, almost an improvisatory quality that is immediately

attractive and frequently captivating. Lest risk taking and bravura

be thought her distinctive qualities one should also listen to

the beautifully weighted chordal playing in the slow movement

– and as for bravura, well, she clearly had a big technique but

also at times a splashy one. In the finale though despite slips

there is a vibrancy and sense of adventure that is distinctive

and very real. In her accustomed Beethoven we find a true balance

between the choleric and the elevated; she understands Beethoven’s

humours, she can play with raucous drama or with elegance and

can effortlessly fuse the two in musical terms. This is a very

alive performance; it’s rhythmically on its toes without sounding

at all rushed, and in the slow movement Fritz Zaun gives us an

orchestral introduction of almost Brucknerian spirituality. Here,

the apogee perhaps of her playing, she is flexible but forward

moving and in the finale she triumphantly drives to the conclusion,

barely bothering to notice the finger slips.

The trio is completed by a blistering performance

of the Strauss Burleske, a work that really responds to her sense

of drama and drive and on the wing musicianship. The tricky side

joins here have been well managed though the copies used are rougher

sounding than the companion discs. There is I believe no competition

for these performances in the catalogue – and Tully Potter’s notes

set the seal on a distinguished, exciting and thought provoking

disc.

Jonathan Woolf