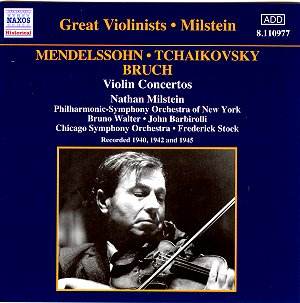

This trio of concerto recordings demonstrates

why Milstein was held in such esteem. Naxos has already released

his contemporaneous discs of the concertos by Glazunov and DvořŠk,

his first traversals of those two works, and now adds the Mendelssohn,

Tchaikovsky and Bruch G minor. They catch the violinist

in his early to middle prime, technically impeccable and an aristocratic

presence. The Mendelssohn with Bruno Walter has a real sense of

discovered freshness to it and ardent lyricism as well. The sense

of freedom is one aspect of Milstein and Walterís translucent

musicality here, as is the soloistís bewitching cantilena. He

is unaffected and memorable in the Andante and deeply noble and

with his conductorís bracing support brings crisp elegance to

the finale; not too fast either.

He recorded the Bruch three times commercially

and here he has the support of John Barbirolli and once again

the Philharmonic-Symphony in tremendous form. Barbirolli opens

powerfully and Milstein responds in kind; not over emoted and

with vibrato perfectly scaled to the demands of the music. He

is really quite withdrawn and introspective in the Adagio, powerfully

so indeed, and Barbirolli brings out the horn harmonies in a way

that seems to reveal them for the first time. There is romantic

fervour but also passagework clarity and digital cleanliness in

the finale. Especially memorable is the way Barbirolli prepares

for Milsteinís passages of increased expressivity Ė a model of

concerto accompaniment and creative collaboration Ė where the

Russianís vibrant statement of the theme is bathed in a wonderfully

romanticised efflorescence.

The Tchaikovsky is accompanied by the Chicago

Symphony and Frederick Stock and is the earliest of the three

performances. He employs some of the standard Auer cuts, as was

to be expected. He was always something of an aloof proponent

of this work and one who established his command from the outset.

Itís not an especially emotive reading though Milstein intensifies

his vibrato at optimum moments of lyric ardour, his trill tightly

focused. There is simplicity and repose in the slow movement without

recourse to smeary intensities but the finale is another matter.

Milstein really whips up a storm here; Allegro Vivacissimo indeed

and an acceleration too far for me. But what playing and control.

Notes are by Tully Potter and transfers are by

Mark Obert-Thorn. Only one problem for me and thatís the side

joins; that leading from the first to the second movement of the

Bruch has clearly caused problems and the join at 4.20 in the

Adagio of the same work is poor. Sony has released the Mendelssohn,

Biddulph the Bruch and the Tchaikovsky though theyíre not, I believe,

currently available.

Jonathan Woolf

Marc Obert-Thorn remarks

I must take issue with Jonathan Woolf's criticism

of the side joins in the Milstein/ Barbirolli Bruch Concerto which

I transferred for Naxos. I don't mind differing opinions with

regard to my choices of equalization or filtering, as those are

highly subjective matters; however, when my side joins are called

"poor," well, as they say in the Westerns, "them's

fightin' words!"

First, as I mentioned in my Producer's Note for the release,

the transfers were all taken from LPs which had themselves been

transferred from the lacquer master discs. American Columbia's

practice at the time was to record directly to 33 1/3 rpm lacquers

in four-minute segments, and then to dub the 78 rpm matrices from

them. The technology available at the time made the 78s re-recorded

in this fashion rather murky, and the sound was not helped by

the shellac in use during this period.

The advantage came when the lacquers were dubbed to LP. The lacquers'

wide frequency range, which could not be captured on 78s, could

finally be heard. Thus, the LP transfers are the best way to hear

these recordings. One side effect of using LPs as a basis for

a CD transfer, however, is that one has to accept the editing

that was done at the time. If a side join was botched on the LP,

there's not much that can be done about it now.

Having said that, however, I disagree that the join between the

first and the second movement of the Bruch is as problematic as

Mr. Woolf claims. I just re-listened to a copy of my master tape

(I don't have the finished CD yet), and had to replay it a few

times, increasing the volume each time, to hear that there was

a slight difference in the level of surface noise between Sides

2 and 3 of the lacquers as they were joined here.

There is more of a difference in the second join he notes, that

in the middle of the slow movement (between Sides 3 and 4); but

it is clear that this difference is caused by the lacquer of Side

3 getting slightly noisy toward the end in relation to the more

quiet beginning of Side 4. It's more noticeable, granted, but

I would hardly call it "poor" as Mr. Woolf does. I've

heard some really poor joins on CD transfers, and this is not

in the same league.

(For what it's worth, I *was* able to fix one between-side gap

in the Mendelssohn Concerto on the same disc. The space left between

the second and third movement seemed to me to be too long, and

I used an overlap join to tighten it up a bit.)

I've noticed that of late, Mr. Woolf has been on a bit of a crusade

with regard to this issue. In his review of my Acts I and II of

"Die Walkure" with Melchior, Lehmann et al. published

Monday, he singles out for criticism "one less than imperceptible

side join" (out of a total of 33 side joins I made in the

entire two-CD set) as well as "some muffled but audible crackle

in one of the sides." This seems to me to be a bit nit-picky.

I can only hope that Mr. Woolf will apply the same standards to

all the historical reissues he reviews as he does to mine.

Yours,

Mark Obert-Thorn