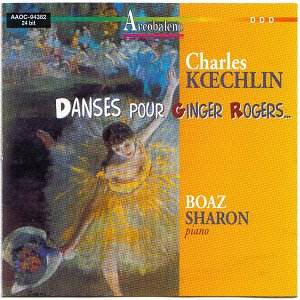

The Arcobaleno label have released a superb and

fascinating recording of small-scale piano works entitled Danses

pour Ginger Rogers. These are from the pen of maverick French

composer Charles Koechlin and are played by Israeli soloist Boaz

Sharon.

The descriptive title of this release Danses

pour Ginger Rogers has clearly been selected by the record

company for gimmicky marketing purposes but is rather misleading.

It could prove slightly confusing for prospective purchasers as

in fact only the first track Danse lente of the

twenty four piano pieces included by Arcobaleno has come from

works that Koechlin composed in recognition of the Hollywood actress,

singer and dancer, Ginger Rogers.

Koechlin is a composer with a low profile and

disappointingly few of his works have been recorded. Readers may

wish to read more about this charming composer with an extremely

complex personality and I have included biographical details of

Koechlin in this review.

Born in Paris in 1867 the enigmatic and extraordinary

Charles Koechlin was a prolific composer in many genres from large-scale

symphonic poems to miniature solo piano works. He was a late-developer

as a composer and remains relatively unknown today. I’m certain

that only the most enthusiastic music-lovers will have heard any

Koechlin scores other than The Jungle Book (1899-1940)

cycle of five symphonic poems and The Seven Stars’ Symphony

Op.132. However there has been recent interest in his works.

There are now several recordings in the catalogue and more in

the pipeline.

Koechlin desired to have all his scores performed

at least once but would not bend away from his most individual

style of composition just to obtain performances. Contrary to

popular belief Koechlin did strive to gain recognition for his

works and to have them accepted by publishing houses and influential

conductors so as to reach the ears of as many discriminating listeners

as possible. Koechlin would not alter his style of composing or

change his high artistic principles for any purpose, such as to

obtain commissions and certainly not for reasons of short-term

popularity for mass market commerciality. This idealistic ‘ivory

tower’ existence may have suited Koechlin artistically but it

frequently resulted in many devastating disappointments and frequent

and severe financial difficulties. However when his country chose

to honour him with the Légion d’honneur he refused to accept

the award which was in keeping with his spirit of independence.

Throughout Koechlin’s long composing career he

retained both the love of the symphonic poem and a predilection

for highly romantic and exotic subjects. Regardless of many shattering

knock-backs he remained an unassuageable optimist, stating,

"To sum up in a word I have confidence

in the future of my music… For not only do I think that people

will recognise the value which most young composers of today place

on my works, but I equally believe that the public will come to

agree with them too."

Despite only sporadic interest showed in his

compositions Koechlin explained that he was convinced that his

works would gain in value over time, and after his death,

"Once a composer is classed as worthy

of admiration, some fifty years or a hundred years after his death…

then everyone becomes overwhelmed at the start of a concert in

which the conductor is to ‘reveal’ the ‘newly discovered master’."

Koechlin revered the music of J.S. Bach and Fauré

and also admired Mozart, Debussy, Chabrier, Gounod, Chopin, Ravel,

Berloiz, Saint Saens, Liszt, Franck and Satie. Interestingly he

had mixed feelings concerning Wagner and detested the music of

Stravinsky and Richard Strauss. Undeniably Koechlin’s music must

have infused various influences he was not a part of any stylistic

school and took great care to remain original and autonomous.

The popularity and the novelty value of a score held no interest

for Koechlin as he was principally concerned with the enduring

quality of his music. Typically Koechlin would compose several

of his works simultaneously and consequently the date of many

of his works can extend over several years, whilst other works

he could complete in a single day.

It is clear from my researches that Koechlin

had a hopeless obsessive personality and perhaps the best example

is his fixation with movie stars of the early Hollywood ‘talkies’.

Many readers will be familiar with his The Seven Stars’ Symphony

Op.132 which consists of musical portraits of the following

seven stars of the silver screen: Douglas Fairbanks, Lilian Harvey,

Greta Garbo, Clara Bow, Marlene Dietrich, Emil Jennings and Charlie

Chaplin.

In respect of this release it is significant

that Koechlin biographer Professor Robert Orledge believes that

the composer’s smaller scale works, such as the piano pieces contained

on the present Arcobaleno disc, "…are his most consistently

inspired pieces even if they lack the power and breath

of vision of his symphonic scores."

Danse lente from the five Danses

pour Ginger for piano Op.163 No.2 (1937)

It was in 1937 after seeing the film Swing

Time starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers that Koechlin

was inspired to compose the suite of five reverential Danses

pour Ginger Op.163. Danse lente is the opening track

on this release which has not surprisingly been described as ’the

fourth Gymnopédie of Erik Satie’. The track has captivated

me and has hardly been off my CD player. The piece, a soft-focused

waltz, lasts only 3:38 and is a real discovery that demonstrates

Koechlin’s imagination and the influence of the French impressionist

school. The haunting quality and sensuousness of the Danse

lente is satisfyingly and charmingly presented by Boaz Sharon.

There is no doubt that the soloist is perfectly suited to the

demands of this work and it left me wanting to hear Sharon record

the complete suite.

Eight pieces selected from Les Heures Persanes

for piano Op.65 (1913-19)

Koechlin’s love of Arabic subjects is heard here

in his suite of eight of the sixteen small scale piano pieces

Les Heures Persanes Op.65 composed between 1913-19. These

were inspired by the orientalism of Pierre Lôti’s novel

Vers Ispahan (1904). Koechlin attempts to evoke and re-create

Arabic music. He likened Les Heures Persanes to an imaginary

journey to Isfahan. Koechlin loved foreign travel and it is ironic

that the composer had never visited Persia although he had holidayed

in Turkey and several North African countries. Clearly Koechlin

was fond of Les Heures Persanes as two years after completing

the suite the composer made an orchestral version of the score

which has been recorded on Marco Polo.

From his polytonal period of piano writing Koechlin

did not design Les Heures Persanes for virtuoso display,

it is predominantly atmospheric, relaxed and dreamlike in mood.

This is a Debussy-like piece where Boaz Sharon offers a genuine

feeling of belief in Koechlin’s semi-improvised world; the soloist

seems to be considering his next chords at random. Throughout

Sharon provides the necessary sensitivity and lightness of touch

in the challenging dynamics and tempo demands and successfully

mixes a wide palette of colours. Particularly successful is how

expertly Sharon plays Koechlin’s

Arabesques (track 6) surely a raindrop

prelude with its ‘Islamic decoration’ and bravura ending

and in Clair de lune sur les terraces (track 4) which includes

the impression of ‘moonlight’. The unmistakable shadow of Ravel’s

Ondine appears in La Paix du Soir au Cimitière

(track 7), whereas, in the final piece, the gritty Derviches

dans le nuit, the listener may feel he has entered a world

explored by master jazz improvisers, Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea.

The Chandos label have recently released the

complete Les Heures Persanes Op.65 played by Kathryn Stott

on CHAN 9974 (editor’s note: there is also a recording by Herbert

Henck on Wergo). At the time of writing I have not heard the Chandos

disc although several reviews look favourably on Stott’s performance

in these challenging works.

La prière de l’homme from Album

de Lilian Vol. 2, for piano Op.149 No.8 (1935)

Earlier in 1934 Koechlin had seen the actress

Lilian Harvey in the film Princesse à vos orders. Koechlin

began a two year infatuation with Harvey, now long forgotten by

the film world, and composed an amazing one hundred and thirteen

works in homage to his idol. La prière de l’homme (track

nine) is the last in a set of eight short and contrasting pieces

composed in 1935 for various instrumental combinations entitled

Album de Lilian Vol. 2, Op.149.

Inspired by the Lilian Harvey film Quick,

the chorale La prière de l’homme is an elegant

and meditative statement with melodic memorability and a strong

Satie-like feel. The opening bars touch on Messiaen’s contemplative

meditations and yet there is a twist as these are almost gospel/jazz

chords and defy categorisation. With refinement of tone and colour

Boaz Sharon beautifully realises the work’s expressive possibilities

with a real sense of belief in this fascinating music.

Quatre nouvelles sonatines for piano

Op.87 (1923-24)

Arcobaleno on the CD cover call the these four

works ‘Novellas Sonatines Françaises’ which is not the

correct title. Maybe Arcobaleno are confusing these works with

Koechlin’s Op.60 Quatre sonatines francaises for piano

duet. The correct title is Quatre nouvelles sonatines Op.87

for piano. These are tonal works written in an accessible style

linked to his French folksong roots that the composser thought

would prove familiar to listeners.

Koechlin adopts a clearly more focused style

in these fifteen delicate sketches which are brimming with French

elegance of line and purity. French folk-melody mixed with the

lucidity of Couperin and most beautifully wrought too. Koechlin

does not endow the movements with French titles, but in every

other way this is Koechlin’s very own Tombeau de Couperin.

Boaz Sharon whose phrasing is never less than intelligent throughout,

really flourishing in the attractive Fauré-like second

movement Sicilienne of the third Sonatine. Sharon skilfully

gets to the heart of Koechlin’s intentions, discovering a wide

range of pleasurable emotions.

The sound of this Arcobaleno release is fairly

warm and clear. There is some slight blurring around the edges

in forte passages, however this can be kept in check by

not having the volume turned up too high; which is no hardship

with these pieces. The notes on the CD case state that the recordings

were made back in 1983. Although we are not told I suspect that

this material has been previously released, perhaps several times

on different labels, over the twenty year period.

I wish to thank Professor Robert Orledge for

his kind permission to use the above quotations from his definitive

biography of Charles Koechlin: ‘Charles Koechlin (1867-1950)

His Life and Works’ written by Robert Orledge. Paperback published

by Routledge (1989) ISBN 3718606097 & Hardcover published

by Harwood ISBN 3718648989.

The beauty of this album is its appeal to the

lover of Debussy and Satie but can be placed comfortably alongside

Zbigniew Preisner’s 10 Easy Pieces For Piano or those ‘cool

jazz’ albums from Davis, Baker, Coltrane, Parker et al that

are currently enjoying a revival.

Koechlin admirers will relish this sterling release

from Arcobaleno and I couldn’t think of a more perfect recording

for those wishing to explore the sound-world of this wonderful

composer for the first time.

Michael Cookson