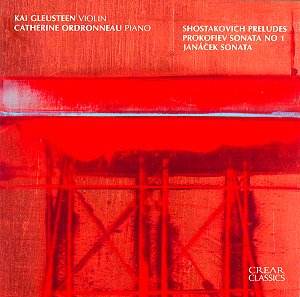

This

is an enterprisingly planned recital that contains one out-and-out

masterpiece, one near masterpiece and some very worthwhile ditties.

The main works are, of course, the Prokofiev and Janáček

sonatas and competition is hot in both pieces. In the Prokofiev

the young artists on this Avie disc find themselves up against

Perlman/ Ashkenazy, Mullova/Canino, Kremer/Argerich, Mintz/Bronfman

and, best (or worst) of all, Repin and Berezovsky, whose 1995

Erato disc won great acclaim. In the Janáček competition

is slightly less fierce, but we still find the likes of Christian

Tetzlaff (with superb partnering from Leif Ove Andsnes), Kremer

and Argerich again and a superb historic Supraphon disc from the

inimitable Josef Suk and Jan Panenka.

So

the planning of this new disc is important. All the competition

listed above puts the two Prokofiev Sonatas together with lighter

couplings, but general consensus is that the first is the finer

piece (some might argue otherwise) so the Avie disc puts its eggs

in this basket and gives us the Janáček and quirky Shostakovich

as fillers. It makes a good sequence, starting with the Janáček

and ending with the much weightier Prokofiev. It’s unlikely that

the Shostakovich transcriptions will really sway the issue, so

it’s down to the two sonata performances to convince the listener

of the merits on offer here.

The

first thing to get used to is the recording. The booklet picture

shows an empty studio, with polished wooded floors, as one might

expect of a modern recording space. The trouble is, for such intimate

music it sounds a shade too reverberant for my liking. There is

a considerable echo delay, as if they are in an empty church,

but the miking is close, so the aural sound stage takes a bit

of adjusting to, especially in louder piano passages. Having said

that, one does get used to this and the quality of the playing

more than compensates. All the usual hallmarks of late Janáček

are in his Sonata, and these artists are alive to its many nuances

and subtleties. This music comes off best when it sounds improvised,

as here, and there are many examples where the spontaneity completely

wins the listener over. The lovely central ballade is one

such episode, and the final adagio is most moving.

The

Prokofiev needs a muscular tone, and the composer was the first

to admit that the piece had a rather serious, almost severe character,

especially compared to the second sonata. This is in evidence

from the very start, where the sombre mood is precisely gauged

by these artists, Gleusteen’s steely tone having a suitably ‘Russian’

edge. The playing here has one thinking of the somewhat spurious

programme that has been attached to the piece over the years (the

struggle of the Motherland, a young girl’s lament etc), and such

is the intensity of the performances that one soon forgets other

players. The difficult rhythmic finale comes off superbly, with

Ordronneau’s piano playing worthy of special mention.

I

may have seemed dismissive of the Shostakovich prelude transcriptions

above, but they do make delightful fillers, working surprisingly

well for violin and piano. The wit and irony suit the move to

violin, with the piano able to play much of its original material

intact. The individual preludes are full of character, and keen-eared

listeners may recognise No.15 as the theme tune to the popular

Richard Briers comedy Ever Decreasing Circles.

This

disc is worth considering, though whether it would displace favourite

versions of the main works is questionable. It works well on its

own terms as an enjoyable recital, and the slightly cavernous

sound may bother others less than me. Good notes by Julian Haylock,

though the blue print against light blue background makes them

very hard to read.

Tony

Haywood

Jonathan Woolf

has also listened to this recording

This is an attractively

programmed disc but it’s been badly

recorded. The Crear Studios are highly

resonant and the spatial separation

that’s also a noticeable feature of

this recording leads to balance problems,

not least on a number of occasions where

the piano overpowers the violin or covers

it. This is a pity because this is clearly

a sympathetic duo pairing, young musicians

of discrimination and taste, and they

do manage to emerge from the unsympathetic

acoustic with some honour.

As for the recital

two powerful and movingly intense twentieth

century sonatas frame Dmitri Tsiganov’s

transcription of the Op.34 Shostakovich

preludes. Of the two it’s the Prokofiev

that is the better understood. The Janáček

is not a work that plays itself and

nor is it one that responds well to

over febrile characterisation – it has

more than its share of contrast and

toughness as it is. The Gleusteen-Ordronneau

duo is unfailingly eloquent technically

but tends to exaggerate incident,

not least in the first movement where

they are much quicker than, say, the

classic pairing of Suk and Panenka.

The effect of the young duo’s abruptness

and convulsive phrasing is, ironically,

to smooth over the fissures inherent

in the music and the jerky violence

sometimes descends to gabble. I don’t

mean to sound indifferent to their playing,

which is of itself fine, but the slow

movement lacks colour and etching of

lines – too much of it sounds inactive,

even, dare I say it, generalized late

Romanticism. I’m sure the boomy acoustic

doesn’t help their cause. They try far

too hard in the Allegretto, attempting

to characterise each passing incident,

though this is genuinely involving playing.

My criticism centres rather on the lack

of integration of passages and also

a certain lack of authentic strangeness.

The concluding Adagio is taken at a

good tempo and the playing here is considered

and highly musical though I should add

that time will give Gleusteen the chance

to widen the subtlety of his vibrato

usage and for the duo to take their

chance with some rubati – both of which

devices are underused. I can’t recommend

this performance, obviously – and thinking

about it I wonder how long they have

had the sonata under their fingers.

It sounds as if they recorded it far

too early and I’d like to hear what

they make of it in a few years time,

with some recital performances under

their belts.

The Prokofiev sounds

rather better. I thought that they indulged

in too many ritardandi and accelerandi

in the first movement however. Gleusteen

is an elegant and persuasive player

but he rather lacks as yet the tonal

heft for this kind of writing and I

missed the remorseless logic and long

bowed power of Oistrakh and pianist

Frieda Bauer in this work. The distant

mike placements and acoustic are a price

to pay in the Allegro brusco – it makes

assertion difficult and rather diffuse.

But the lyrical sections are deeply

romantic, even Brahmsian, though one

might prefer Oistrakh’s simplicity and

refinement, his touching

delicacy. I felt in the Andante much

as I did in the Janáček – this

duo is strong on local incident but

not yet on the broader canvas. I wish

they would shape phrases in slow moments

more compellingly and it’s no coincidence

that although Oistrakh and Bauer

in their live 1968 recording are by

some way slower than the younger pairing

they sound hugely more incisive. I enjoyed

the duo’s way with the finale – fizzing

and excellent ensemble work, though

maybe the reflective passages weren’t

as well subsumed as they should be.

The Shostakovitch Preludes make a good

central panel. They respond well to

the miniatures – No 3 blessed with an

excellent trill, No 10 veiled and solemn,

No 15 flecked with humour and No 17

genuinely elegant.

I’ve rather laboured

the duo’s relative failings – or what

I take to be their failings – because

I think they are genuinely talented

musicians who have not lived quite long

enough with the repertoire to do it,

and themselves, justice. The recording

is also against them. I’d like to hear

them in a proper acoustic next time,

recording some Debussy.

Jonathan Woolf