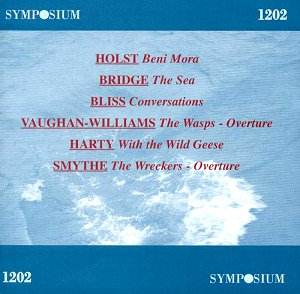

British recording studios were busy places in

the 1920s. An earlier generation of senior composers, among them

Elgar, German, Mackenzie and Stanford had made recordings in the

teens of the century but the younger generation also proved attractive

to HMV, Columbia and the newcomer Aeolian Vocalion. The imprimatur

of a composer-led recording was obviously a selling point during

this time, as now, and despite the relative limitations of recording

technology – four of the six works were recorded under the acoustic

system – these are documents of lasting value.

Symposium lead off with the Holst, which as far

as I know has never appeared on CD before. Columbia were making

some fine sounding "new process" records in 1924 but

even they couldn’t quite do justice to a work of diffuse colour

such as Beni Mora. Holst’s ingenious instrumental layering doesn’t

reproduce with any degree of precision in the recording but what

does come across is the characteristically taut Holst hand on

the tiller – brisk tempi, tight rhythms and a powerful sense of

momentum. Frank Bridge was not a keen student of the recording

studio and his conducting was certainly not universally admired.

He complained about the crudity of the recording process and this

recording, of The Sea, in particular. I suspect it was some balancing

exigencies that irked him – the harp is deliberately over recorded

so that it can sound in the balance – as well as a sense of urgency

in matters of tempi. Nevertheless I have to say that whatever

the reduction in the strings the piece still manages to exert

its magic, the portamenti in the Sea Foam movement being succulently

liquid.

Bliss’s Conversations is probably the least well

known of the performances and indeed of the pieces (has it ever

been re-released since its original 78 inscription?) Its very

cosmopolitan wit seldom palls – not least because we hear it so

infrequently– and there is an idiomatic freshness in this performance.

The grandly named symphony orchestra is actually a quintet but

an anonymous one. The original performers back in 1921 were a

redoubtable collection of the wise and the youthful – Charles

Woodhouse, Raymond Jeremy, Cedric Sharpe, Gordon Walker and Leon

Goossens and I’ve a feeling that a few of them are here. VW’s

Wasps gets a fine 100-yard dash of a reading. Vocalion’s pick-up

house band was on hand to supply the thrust and nobility – and

rippling harp near the acoustic horn alongside bass reinforcements

for "downstairs" Pity about the imperfect side join.

Hamilton Harty was no stranger to the recording studios of course,

as soloist, accompanist, chamber player and, not least, conductor.

This is the first of the two electrics and is a passionate and

vibrant reading of this noble score. One can admire the very distinctive

timbres of many of the Hallé’s principals as well as the

stirring portamenti of the violin section whose playing of Harty’s

cantilena is memorable. Ethel Smyth recorded the overture to The

Wreckers in 1930 – a typo has her as ‘Smythe’ in the booklet.

She may have been an utter pain to Thomas Beecham, Adrian Boult

and anyone else who conducted her music but she proves a bold

and imaginative conductor of her own music – presumably after

ticking herself off a few dozen times. Saturated though it is

in Wagnerian power it strikes a lyrical and forward moving note

in this incisive and well-recorded performance.

The copies used are pretty good. Engineering

has been discreetly applied. In the days of the LP Pearl issued

a few of these performances, along with a number of other conductor

led works, but Symposium’s transfers are comfortable and easy

to listen to.

Jonathan Woolf