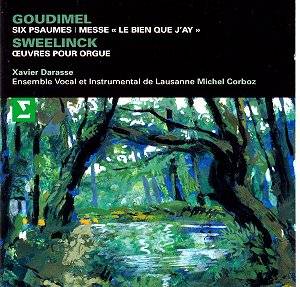

This recording was first issued in 1975 but since

then the catalogue has not been overwhelmed with recordings of

Goudimel’s music. Apart from the inclusion of a few works in various

anthologies, the only other major disc of his music seems to be

Naxos’s Psalms of the French Reformation.

Claude Goudimel was born in Besançon in

1514 or the thereabouts. He lived most of his life in Paris, Metz

and Lyon. He was at the University of Paris in 1549 and worked

for the Parisian printer Nicoal Du Chemin. Goudimel was in Metz

for 10 years from about 1557, where he developed close ties with

the Reformed Church. He died in Lyons, one of the victims in a

massacre of Protestants which followed from the St. Bartholomew’s

day massacre in Paris.

Goudimel’s works are predominantly settings of

French psalm translations based on the Geneva psalter. These hundreds

of polyphonic psalms far outweigh the surviving songs, motets

and masses. The psalms all came with official tunes and Goudimel

uses these in two different ways. In ‘Or sus tous humains’ (Now

arise all men – a paraphrase of Psalm 47), the work makes uses

of imitation of motifs based on the official psalm tune. In other

works such as ‘O Seigneur loue ser’ (O Lord, praised shall be

– Psalm 130) and ‘Du fons de ma pensée’ (From the bottom

of my thoughts – Psalm 75), Goudimel uses the psalm tune as a

cantus firmus in the tenor. The two settings ‘Laisse moi desormais’

(Song of Simeon) and ‘Mon coeur rempli’ (My heart full) use texts

which were fitted later to pre-existing Goudimel settings of other

psalms. The notes do not explain why the original Goudimel psalm

settings were not used in these two cases.

These are not public works; the psalm settings

were written for private use as the Protestant worship of the

time only allowed the official tunes to be used. So we should

imagine a small group of musically talented Protestants coming

together in a domestic setting to sing these for devotional entertainment.

The come over as a mixture of conventional hymn-like pieces and

the fuguing songs of the 17th and 18th century

English church. Goudimel is careful to keep the words audible

at all times. The motet style pieces which use imitation sound

as if they would be rather fun to sing. And this is a pointer

to the problem with all the psalms; the musical material is not

really of sufficient interest. These are pieces for performers,

the music being subservient to the text but enjoyable enough to

perform. The choir, the Ensemble Vocal et Instrumental de Lausanne,

sound as if they are a large group – you have to take the idea

of a domestic performance with a pinch of salt. The performances

are attractive enough, though the choir sings with a vibrato that

is probably unsuitable for music of the period. I would like to

hear smaller scale, more delicate performances of these pieces.

Goudimel wrote five surviving masses, all are

parody masses. "Missa Le bie qu j’ay" is based on the

song "Le bien que j’ai" by Jacques Arcadelt. Here it

is sung interspersed with plainchant propers, though the booklet

does not make this clear. As with the psalm settings, this seems

to be music written primarily to be useful and functional, (I

could even imagine the Goudimel mass being useful to a modern

day Latin Mass choir such as the one in which I sing). The musical

material never overwhelms the text, even the passages with four

moving parts are written with a startling clarity. And passages

of homophony (or near homophony) are frequent; there are very

few really extended passages with all four moving parts. The performance

from the choir is adequate, if a bit robust. The vigour of the

performance might reflect the homely style in which the mass was

first performed but it does not bring out the best in the piece.

The Benedictus, sung by solo voices, is one the most moving movements.

Some of the speeds are rather on the slow side, which reflects

the conductor’s generally romantic view of the works. As with

the psalms, the amount of vibrato seems anachronistic and I would

like to hear a smaller scale more subtle performance of the mass.

Rather curiously, the disc is completed by performances

of three organ pieces by Sweelinck, performed by Xavier Darasse.

No information is given about the organ used for these pieces.

Sweelinck was one of those composers whose influence transcended

the rather narrow confines of his personal life. He never left

the Netherlands but his fame as an improviser and the fine quality

and wide range of his pupils meant that his influence spread as

far as Eastern Europe. The performances by Darasse are stylish

and polished. Why they have been tacked on to a disc of music

by Goudimel (the two almost certainly had no links at all) is

anybody's guess.

Robert Hugill