Pianophiles will either wince or smile – according

to taste – at the memory of Abram Chasins’ outrageously florid passages

on English musicians in his book ‘Speaking of Pianists’: All within

this gracious assemblage have long breathed the reposeful air of

England, he wrote with a baroque flourish allowing that I have

been charmed by Myra Hess and her art since I first went to London.

On only a few occasions has her playing been that of a great pianist.

Which of course begs several questions too big to deal with here

though one question does spring to mind; had he heard her Schumann?

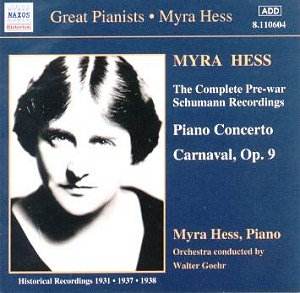

Naxos here compiles all Hess’s few pre-War Schumann

recordings. They display all her virtues of characterisation, tonal

allure, unforced drama and a kind of vanity-shorn rightness that constantly

illuminates the text. There is nothing at all outsize about these performances;

the Concerto in particular doesn’t aspire to the heaven-storming heights

and it is I think, in any case, inferior in terms of greatness of understanding

and conveyance of inner meaning to Carnaval, which here receives

one of the great gramophonic readings. Hess for example would never

have contemplated the piston hammered Papillons of, say, Simon

Barere (he’s in my thoughts because I’m reviewing a live Carnegie Hall

concert but he stands as representative of an altogether different Schumann

aesthetic, a kinetic, vertiginous and sometimes ungovernable one). It’s

difficult to appreciate quite how difficult to achieve is Hess’s naturalness

of expression. Her rubati are unforced, her colourings and voicings

perfectly apposite. The più moto of the Préambule

however is fantastically fluent, her Arlequin truly insouciant,

her left hand in the Valse noble vivid and beautiful, Eusebius

gravely and deeply poetic. Papillon then is fast but not hammered

– it has a skipping elegance not a pneumatic insistence – and if Chopin

is hardly agitato as marked then it loses nothing in depth

of utterance. How many other pianists really explore the rhythmic implications

of the Valse allemande as does Hess; how many reconcile the lyrical

and the passionate that lie at the heart of Paganini. In every

way this is a desert island Carnaval.

The piquancies of Vogel als Prophet are explored

in a 1931 New York recording but the other principal reason for acquiring

this disc is the Concerto. This is her earlier recording; she made another

recording of it in 1954 with Rudolf Schwarz. Still I don’t think memories

of the later recording will efface certain imperishable features of

this earlier one. The A flat major episode in the first movement is

gorgeously but not indulgently poetic, with the echoing clarinet phrases

prominent. Hess’s sense of movement and tempo relation was seldom as

necessary as in this work, and her sovereign control of tonal gradation

treasurable. In the cadenza her quasi-improvisatory way is strongly

animated and persuasive. Her Intermezzo has an elfin and rarefied

charm and she matches her phrasing with that of the orchestral statements

with architectural and tonal sagacity. She absorbs the contrastive sections

of the finale with glittering but cool musicality and there is no heroic

driving peroration. If this finale doesn’t galvanize, ignite, combust

– or what you will – it’s playing entirely consonant with Hess’ approach

as a whole and wholeness was very much her great gift as a Schumann

player.

Nalen Antoni’s thought-provoking note lays bare the

Schumann performance tradition from which Hess emerged. The transfer

of Carnaval is good but I had trouble with the Concerto – there’s

a slightly opaque and muffled quality to it that I found lacked clarity.

As for florid Abram Chasins I have to say I found Hess both charming

and a great pianist, in the Carnaval at least.

Jonathan Woolf