The Mengelberg collector has probably never had it

so good. A continuous array of broadcast material seems to pour forth

– and is frequently bewilderingly recycled – from a number of record

companies. What might seem like a first ever release to the laughable

novice turns out to have been released and had a shelf life many times

over. As one who finds the discographic Mengelbergian thickets tough

to penetrate I won’t venture too far off the path but will start by

saying that this is the second volume Tahra has put out devoted to previously

unissued Mengelberg performances – the first was 391/3, a three CD set.

This second volume collates two aspects of the canonical Mengelberg

– his Beethoven and his promotion of contemporary music, a less appreciated

facet of his overwhelming contribution to Dutch musical life.

His Egmont overture from the Salzburg festival in 1942

is dramatically laced and powerful and is in really first class sound,

as is Euryanthe, which was recorded at the same festival but three days

earlier. This, if anything, is even finer – evocative and outsize and

truly dramatic. The First Symphony (Concertgebouw October 1940) features

outer movements of remarkable breadth. All the Mengelberg stamps are

there: huge personality, orchestral mastery, tonal effulgence and some

characteristically outlandish rubati. It is as performances go the polar

extreme of Weingartner’s commercial recording. It’s a great shame that

the Eroica of April 1940 is missing its opening movement. Given

the existence of other Beethoven performances this is low on the list

of priorities but there is still enormous instruction in Mengelberg’s

Marche funebre, very slow and italicised, and the dramatic diminuendi

of the Scherzo with his equally slow trio. The Mozart from March 1942

is in somewhat less good sound and there are some acetate scuffs.

Max Trapp (1887-1971) studied piano with von Dohnányi

and composition with Paul Juon subsequently teaching at the Berlin Hochschule

für Musik. He also took composition master classes in 1934-35.

His Piano Concerto, composed in 1931 and finding an admirer in Walter

Gieseking, is in three movements and lasts some twenty-seven minutes.

It’s the earliest known surviving Mengelberg broadcast performance.

It opens with some cascading leaps, negotiated with a certain drive

by Gieseking. The orchestration is not quite turgid but it does lack

distinction even though the counterpoint is characteristically fluent.

It develops a certain craggy polyphonic drive – Reger’s influence on

Trapp was decisive in this respect it seems – but fails to develop any

neo-classicist potential. The second movement pursues a questing, unsettled

line and features an absorbed clarinet line but once more there’s precious

little to detain one – beyond the archival interest inherent in its

survival. A small chunk of this movement is missing (I believe it’s

intact on a rival Audiophile Classics release). By the time the finale

comes around the piano is in complete control and leads a boisterous

charge; a nice, elfin violin solo also flecks the score (which increasingly

lightens, shedding the Regerian as it does so) and punchy trumpets bring

the work to an assertive conclusion. Of course it’s important to have

this survivor from the mid-thirties but I won’t be returning to it often.

Not so the Voormolen. Born in 1895 and strongly influenced

by French impressionism his Concerto for two oboes is a delight, a real

charmer. The opening is bright, busy, and gently neo-classical and the

second movement, an Arioso, has charm and overlapping traceries. Both

Jaap and Hakon Stotyjn play magnificently – Jaap, the principal oboist

of the Concertgebouw was one of the very few players incidentally that

the increasingly crabby Léon Goossens had any time for. Both

brothers phrase the Arioso with ineffable delicacy and bring to the

finale a chattering and chundering brio, with its muted trumpet full

of humour, which threatens at any moment to turn the august orchestra

into one big dance band turn. Delightful. Brilliantly played as well.

To round things off there is a very spontaneous sounding

1938 interview, made in Munich and lasting five minutes. The text is

reprinted in the documentation to these two CDs which consists of a

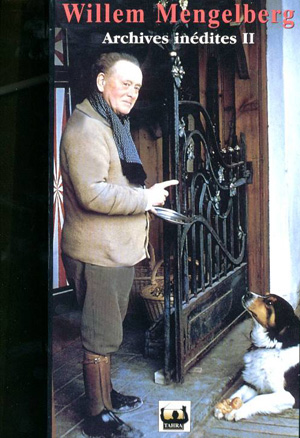

long, tall book sized shape, 10" x 5." The colour photographs

of Mengelberg’s chalet retreat are delightful and the commercial discography

and photos of LPs a splendid touch (though in my eagerness to scrutinise

all this my reviewer’s fingers have managed to detach the booklet from

the covers – watch out). A difficult set to review because of the torso

of the Eroica and the miscellaneous nature of the recordings

generally – but I was greatly taken by performances, works and the unusual

presentation of the set and give it a firm and enthusiastic recommendation.

Jonathan Woolf